The Revolutionary Artists Who Changed Art Forever

The Faces Behind the Revolution

Dadaism wasn’t just a movement— we must ask the question who are dadaists. They were a constellation of remarkable individuals whose collective rebellion against artistic and social conventions permanently altered the course of art history. These revolutionary figures came from diverse backgrounds, worked across multiple disciplines, and brought unique perspectives to a movement united by its rejection of traditional aesthetics and embrace of chance, absurdity, and provocation.

From poets to painters, photographers to performers, Dadaists collectively dismantled artistic hierarchies and challenged fundamental assumptions about creativity. Here we explore the most significant Dadaist artists and their lasting contributions to our understanding of what art can be.

The Zurich Pioneers: Founding Figures

Hugo Ball (1886-1927)

German poet, writer, and performance artist Hugo Ball stands as perhaps the most crucial founding figure of Dadaism. As co-founder of Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire, he created the essential platform where Dadaism was born. Ball’s sound poetry performances—particularly his recitation of “Karawane” while wearing a shaman-like costume of his own design—embodied Dadaism’s rejection of rational language. His 1916 Dada Manifesto provided the movement’s first theoretical framework, claiming he coined the term “Dada” by randomly selecting it from a dictionary.

Emmy Hennings (1885-1948)

Though often overshadowed in Dadaist histories, Emmy Hennings was equally important in establishing Cabaret Voltaire alongside her husband Hugo Ball. A poet, performer, and puppeteer, Hennings managed the cabaret and performed nightly, bringing her experience from cabaret circuits across Germany. Her published works drew on her experiences of poverty and imprisonment to create emotionally powerful literature that contrasted with Dadaism’s more cerebral approaches. Hennings’ performance style—incorporating puppetry, singing, and recitation—helped establish the interdisciplinary nature central to Dadaist expression.

Tristan Tzara (1896-1963)

Romanian-born poet Tristan Tzara transformed Dadaism from a local Zurich phenomenon into an international movement through his tireless promotion and publication efforts. As editor of the journal Dada, he disseminated Dadaist ideas worldwide through manifestos, poems, and theoretical texts. Tzara’s instructions for creating poetry by drawing random words from a hat exemplified Dadaism’s embrace of chance operations, while his theatrical provocations at Parisian events epitomized the movement’s confrontational approach to audiences. His complex relationship with Surrealism—initially embracing then rejecting André Breton’s leadership—highlights the tensions that ultimately transformed Dadaism into new artistic directions.

Jean (Hans) Arp (1886-1966)

Alsatian-born Jean Arp (also known as Hans Arp) and his wife Sophie Taeuber-Arp are often credited with creating some of Dadaism’s most important artistic innovations. Working at the intersection of sculpture, painting, and poetry, Arp pioneered the revolutionary use of chance as a creative principle, fundamentally challenging traditional notions of artistic control and intention.

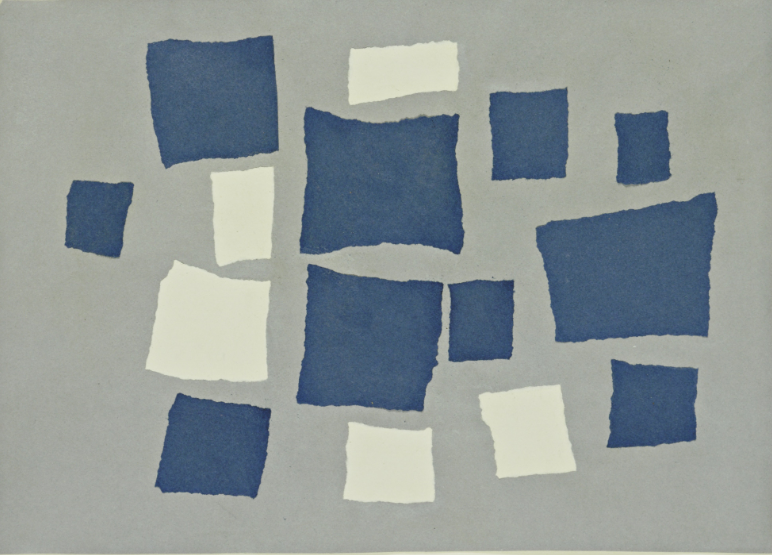

Arp’s groundbreaking “chance collages” employed a method both simple and profound: standing above large sheets of paper, he would drop small squares of colored paper and then glue them precisely where they landed. This technique—documented in works like “Untitled (Collage with Squares Arranged According to the Laws of Chance)” (1916-17)—deliberately surrendered artistic control to gravity and randomness, provoking visceral reactions from viewers accustomed to carefully composed art.

This embrace of chance was partially inspired by Arp’s interest in I-Ching coins used in Chinese divination, reflecting his fascination with systems that accessed creativity beyond rational control. Deeply frustrated with geometrically correct art arrangements that he saw as artificial and constraining, Arp explicitly labeled his Dada work as “anti-art”—rejecting established aesthetic principles in favor of processes that mirrored nature’s organic randomness.

Beyond his collages, Arp’s biomorphic sculptures with their flowing, organic forms provided a distinctive visual vocabulary that influenced generations of abstract artists. His close collaboration with Sophie Taeuber-Arp exemplified Dadaism’s cooperative spirit, while his later involvement with Surrealism and Abstraction-Création demonstrates how Dadaist principles continued evolving into subsequent artistic movements.

The Iconoclastic Innovators: Transforming Art’s Boundaries

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

Few artists transformed our understanding of art as profoundly as French-American Marcel Duchamp. His revolutionary concept of the “readymade”—ordinary manufactured objects elevated to art status through artist selection and contextual displacement—challenged traditional notions of craftsmanship and aesthetics. Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a urinal signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt,” remains perhaps the most influential artwork of the 20th century. Beyond readymades, works like The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-23) combined mechanical elements, chance operations, and complex conceptual frameworks that anticipated developments in conceptual art decades later.

Man Ray (1890-1976)

American-born Emmanuel Radnitzky, known as Man Ray, revolutionized photography through techniques that transformed the medium into a legitimate avant-garde art form. His “rayographs” (photograms created by placing objects directly on photosensitive paper) eliminated the camera entirely, while his solarization technique produced dreamlike transformations of conventional photographs. Beyond photography, Man Ray created provocative objects like Gift (1921)—an iron with metal tacks attached to its surface—that transformed everyday items into menacing, unusable artifacts. His presence in both New York and Paris Dada circles helped cross-pollinate ideas between continental and American avant-gardes.

Hannah Höch (1889-1978)

As the only female member of Berlin’s Dada Club, Hannah Höch pioneered photomontage as a critical technique for social and political commentary. Her masterpiece Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919-20) combined images from mass media to critique politics, gender roles, and technology. Höch’s work consistently addressed women’s experiences in modern society, juxtaposing images of “New Women” with machinery and political figures to expose contradictions in gender expectations. Despite marginalization even within the avant-garde, her technical innovations and feminist perspective have secured her recognition as one of Dadaism’s most significant contributors.

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948)

Rejected by Berlin Dadaists for his perceived bourgeois tendencies, German artist Kurt Schwitters developed his own artistic approach called “Merz”—a term derived from a fragment of the word “Kommerz” (commerce). His collages and assemblages incorporated urban detritus—tram tickets, broken furniture, newspaper fragments—transforming discarded materials into complex compositions that anticipated later developments in assemblage and installation art. Schwitters’ magnum opus, the Merzbau, transformed his Hanover home into an ever-growing sculptural environment that anticipated installation art by decades. His sound poem “Ursonate” (1922-32) similarly pushed the boundaries of poetry into pure sound composition.

The Political Provocateurs: Dada as Weapon

John Heartfield (1891-1968)

Born Helmut Herzfeld, John Heartfield anglicized his name as a protest against German nationalism during World War I. He developed photomontage into a powerful political weapon, creating seamless compositions that delivered devastating critiques of Nazism. Works like Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk (1932) used humor and visual metaphor to expose fascist propaganda. Heartfield’s montages, reproduced in leftist publications like AIZ (Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung), demonstrated how Dadaist techniques could be harnessed for explicit political communication, influencing political graphic design to this day.

George Grosz (1893-1959)

German artist George Grosz unleashed caustic visual critiques of German society through his scathing drawings and paintings. His caricature-like portrayals of military officers, industrialists, and the bourgeoisie exposed corruption and hypocrisy with unflinching directness. Works like The Pillars of Society (1926) combined precise draftsmanship with moral outrage, creating images that still shock with their uncompromising social criticism. Grosz’s 1920 collaboration with Heartfield, The Art Scab, attacked conventional art while promoting revolutionary politics. After emigrating to America in 1933, Grosz continued his artistic career but never recaptured the biting intensity of his Berlin Dada period.

Raoul Hausmann (1886-1971)

Austrian artist Raoul Hausmann, self-proclaimed “Dadasoph,” combined philosophical depth with revolutionary technique in his Berlin Dada work. His iconic Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Age) (1919)—a wooden mannequin head adorned with measuring devices and mechanical parts—perfectly captured Dadaism’s critique of modern rationality and mechanization. Hausmann’s photomontages incorporated text, images, and typographic elements to create visual-verbal compositions that disrupted conventional reading. His “poster poems” similarly arranged letters in nonlinear patterns that anticipated concrete poetry and graphic design developments.

Johannes Baader (1875-1955)

Perhaps the most radical Berlin Dadaist, architect Johannes Baader (who styled himself “Oberdada”) specialized in public interventions that brought Dadaist chaos directly into civic spaces. His most notorious action—disrupting a service at Berlin Cathedral to proclaim himself the Holy Ghost—exemplified Dadaism’s attack on religious and state authority. Baader published his pronouncements as paid advertisements in newspapers, created elaborate architectural fantasies he called “spiritual buildings,” and constructed the massive assemblage Germany’s Greatness and Decline for the First International Dada Fair (1920), further blurring boundaries between art and public provocation.

The Multimedia Experimenters: Crossing Artistic Boundaries

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943)

Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp exemplified Dadaism’s interdisciplinary spirit through her work across multiple media. Trained in textile design, she created geometric abstractions in embroidery, beadwork, painting, and sculpture that challenged distinctions between fine and applied arts. Her Dada Head sculptures transformed wooden millinery forms into modernist abstractions, while her interior design work for the Aubette nightclub in Strasbourg integrated abstract art into architecture. As a dancer at Zurich’s Laban School and performer at Cabaret Voltaire, she embodied Dadaism’s rejection of disciplinary boundaries. Her tragic death from carbon monoxide poisoning in 1943 cut short a remarkable career that influenced both abstract art and design.

Francis Picabia (1879-1953)

French artist Francis Picabia embodied Dadaism’s rejection of stylistic consistency through his deliberately contradictory artistic evolution. His “mechanomorphic” drawings of the 1910s depicted humans as machines, satirizing modern society’s technological obsession. Later, his intentionally crude figurative paintings mocked artistic conventions of skill and taste. As editor of the journals 391 and Cannibale, he published provocative texts and images that extended Dadaism’s reach. Picabia’s constant reinvention—moving through Impressionism, Cubism, Dadaism, and later styles—demonstrated his commitment to artistic freedom and rejection of fixed identity, making him one of modernism’s most mercurial figures.

Max Ernst (1891-1976)

German artist Max Ernst pioneered techniques that bridged Dadaism and Surrealism. His frottage (rubbing) and grattage (scraping) methods introduced chance elements into painting, while his collage novels like Une Semaine de Bonté (1934) combined Victorian engravings into dreamlike narratives. As a key figure in Cologne Dada, Ernst collaborated with Johannes Theodor Baargeld on the Fatagaga collage series and organized the infamous Dada-Vorfrühling exhibition that scandalized the city. Ernst’s war experiences informed his work’s psychological intensity, while his technical innovations expanded collage’s narrative and associative possibilities.

Marcel Janco (1895-1984)

Romanian-born artist Marcel Janco created masks for Dada performances that transformed poetry recitals into ritualistic events. His expressionist paintings documented the raw energy of these gatherings, while his architecture training informed his contributions to avant-garde building design. After leaving Zurich, Janco continued exploring Dadaist principles in Romania before eventually settling in Israel, where he founded the artists’ village of Ein Hod. His ability to move between media—from mask-making to painting to architecture—exemplified Dadaism’s rejection of artistic specialization.

The Literary Revolutionaries: Remaking Language

André Breton (1896-1966)

French writer André Breton initially embraced Dadaism’s nihilistic energy before seeking more constructive approaches to exploring the unconscious mind. His Magnetic Fields (1920), co-authored with Philippe Soupault, pioneered “automatic writing”—a technique that would become central to Surrealism. By 1924, Breton’s publication of the First Surrealist Manifesto marked Dadaism’s transformation into a new movement. Though his authoritarian leadership style alienated many former Dadaists, Breton’s theoretical writings provided crucial frameworks for understanding how Dadaist experimentation evolved into systematic exploration of dreams and the unconscious.

Hugo Ball’s 1916 Dada Manifesto, recited at Cabaret Voltaire, represented the movement’s first theoretical statement. Ball’s manifesto introduced the term “Dada” and outlined the movement’s rejection of conventional language: “How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, europeanized, enervated? By saying dada.”

Richard Huelsenbeck (1892-1974)

German poet and drummer Richard Huelsenbeck brought percussive energy to early Dada performances before transporting Dadaist ideas to Berlin. There he published the First German Dada Manifesto (1918) and organized events that gave German Dadaism its explicitly political character. His “Collective Dada Manifesto” (1920) declared: “Dada is German Bolshevism,” emphasizing the movement’s revolutionary politics. After emigrating to New York, Huelsenbeck practiced psychiatry under the name Charles R. Hulbeck while continuing to write about his Dadaist experiences, providing valuable firsthand accounts of the movement.

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927)

Known as the “Dada Baroness,” German-born artist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven embodied Dadaism through her very existence. Her outrageous costumes—incorporating stolen objects, trash, and found materials—transformed her daily life into performance art decades before such practices were recognized. Her experimental poetry used fragmented language and sexual imagery that defied conventions, while her found-object sculptures anticipated later conceptual approaches. Recent scholarship suggests she may have contributed to or even created iconic works attributed to male artists, including the possibility of her involvement with Duchamp’s Fountain.

The International Expansions: Dada Beyond Europe

Beatrice Wood (1893-1998)

American artist Beatrice Wood, who styled herself the “Mama of Dada,” moved between visual art, writing, and performance in New York’s avant-garde circles. Her ironic drawings and satirical texts appeared in The Blind Man, a journal she co-edited with Duchamp and Henri-Pierre Roché. Wood’s later ceramic work extended Dadaist principles into applied arts with ingenious glazing techniques that earned her recognition as a significant ceramicist. Living to 105, she became a living link between historical Dadaism and later generations of artists, her longevity allowing her to witness Dadaism’s long-term impact on art history.

Tsuji Jun (1884-1944)

Japanese poet and philosopher Tsuji Jun introduced Dadaist ideas to Japan through his writings and translations. His magazine MAVO (1923-1925) published works influenced by European Dadaism while adapting its principles to Japanese cultural contexts. Jun’s poetry rejected traditional Japanese literary forms in favor of more experimental approaches influenced by Dadaist language experiments. Though operating far from Dadaism’s European centers, Jun’s work demonstrates how the movement’s ideas transcended cultural and geographical boundaries to inspire global artistic experimentation.

Takahashi Shinkichi (1901-1987)

Japanese poet Takahashi Shinkichi embraced Dadaist approaches to language and incorporated them into Japanese literary contexts. His 1923 book Dadaisuto Shinkichi (Dadaist Shinkichi) introduced Dadaist poetry techniques to Japanese audiences, while his later work explored connections between Dadaist language experiments and Zen Buddhism’s approach to meaning and meaninglessness. Takahashi’s cross-cultural adaptation of Dadaist principles demonstrates how the movement’s rejection of conventional meaning resonated across linguistic and cultural boundaries.

Legacy and Influence: Dadaism’s Enduring Impact

The revolutionary artists who constituted Dadaism created far more than a brief artistic rebellion. Their techniques—photomontage, collage, assemblage, readymades, chance operations, sound poetry, and performance art—fundamentally expanded the vocabulary of modern art. Their challenges to conventional definitions of art, authorship, and creativity permanently altered how we understand artistic production.

Most significantly, these diverse individuals collectively shifted art’s focus from aesthetic pleasure to intellectual engagement, from passive beauty to active provocation. In questioning every aspect of art-making, Dadaists opened possibilities that continue to inspire artists working today across all media. Their lasting influence demonstrates that true artistic revolution comes not just from creating new styles, but from fundamentally reimagining what art can be and do in the world.

Hans Arp and his wife are often attributed with creating the most important Dada Art. Through a series of collages, Hans Arp created art by chance. Standing he would drop small square different colored papers and drop them down onto a larger sheet. Wherever the smaller squares landed he would glue them to the sheet provoking visceral reactions in art. Hans was also interested in I-Ching coins that were apparently used to tell fortunes. Arp was frustrated with geometrically correct art arrangements and labelled his Dada art as ‘anti-art”.

Popular Dada Art

Untitled (Squares Arranged according to the Laws of Chance) (1917)

Hans Arp’s many Untitled (Squares Arranged According to the Laws of Chance) (1917) is a seminal work in Dadaism, challenging conventional artistic composition and embracing randomness as a creative force. This piece consists of torn paper squares dropped onto a surface and then adhered where they landed, rejecting traditional artistic control.

Arp’s process subverted the idea of artistic intent, emphasizing chance as a valid creative method. By surrendering composition to randomness, he questioned the need for order and hierarchy in art, aligning with Dadaist principles of rejecting logic, reason, and structured aesthetics. This approach critiqued the structured rationalism that had led to World War I, positioning Dada as a radical response to the era’s chaos.

Despite its reliance on chance, Squares Arranged According to the Laws of Chance still exhibits a visually balanced composition. This paradox suggests that even in randomness, patterns and meaning can emerge, subtly hinting at nature’s underlying structures. The work also paved the way for later artistic movements like Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, which explored unconscious creation and spontaneity.

Arp’s technique of using chance as a compositional tool influenced later experimental artists, including John Cage in music and Jackson Pollock in action painting. Today, the piece remains a key example of how Dadaism redefined artistic intention and challenged the very definition of art itself.

Performing at Cabaret Voltaire (1916)

Wearing this costume he designed Hugo Ball performed his poem called ‘Karawane’. The poem contained syllables that were nonsensical delivered with different emotions and rhythms creating an emotive work that could not be understood. If words were used they would be stressed especially during vowel sequences. Set below is a Hugo Ball poem –

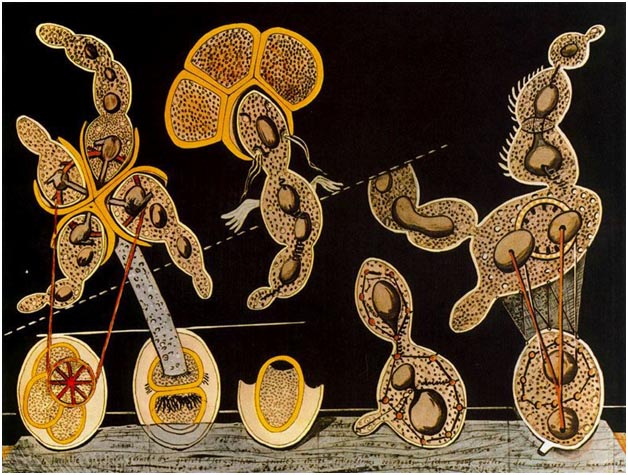

The Gramineous Bicycle (1921)

Hans Arp also worked with Max Ernst and together they brought dada art and Dadaism to Paris. Many people believe dada art had a great impact on future surrealism and cubism art works that would later outgrow the dada movement. An early example of one of their works is the Gramineous Bicycle shown above which shows abstracted elements to create a whole piece. Max Ernst’s art increasingly dealt with human body parts deconstructed to make a dream like visual image. Plant drawings were deconstructed into biomorphic forms foreign to the piece. Ernst collages originated in dada form but later he developed into Surrealistic works.

The Role of Visual Art in Dada

Many Dada artists were not concerned with how their art looked or was perceived but rather with the ideas and emotions their works evoked. For Dadaists, art was not the desired end result but a means to illuminate and achieve a voice that would provide genuine criticism of contemporary society. They maintained a complex relationship with modernity—simultaneously embracing and rejecting the media and technologies that defined contemporary life.

Dadaists radically redefined the boundaries of what art could be by employing pure chance and unorthodox methods, means, and venues to produce provocatively spontaneous works that were often irreverent and sometimes deliberately irrelevant. Collages, games, theatrical performances, scissors, glue, photomontages—anything could be incorporated into Dada art, and nothing was considered taboo.

Perhaps most revolutionarily, Dada art directly challenged the notion that an artist needed formal training or technical skill to create relevant artwork. This democratization of the creative process opened artistic practice to new approaches and practitioners, permanently expanding the definition of who could be considered an artist and what could be considered art.

Who Are Dadaists

Who were the Dadaists and what did they believe in?

Dadaists were a group of artists, poets, and performers who rejected traditional art and embraced chaos, absurdity, and randomness. They believed that rationality and conventional artistic values had led to World War I, so they used their work to challenge authority, mock institutions, and redefine artistic expression. Their aim was to dismantle artistic norms and provoke thought through unpredictability and satire.

Where and when did Dadaists emerge?

Dadaism began in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1916, during World War I, at Cabaret Voltaire, a performance space founded by Hugo Ball. The movement quickly spread to Berlin, Cologne, Paris, and New York, adapting to different cultural and political landscapes. Each location had unique characteristics, with Berlin Dadaists focusing on political critique, while New York Dadaists, like Marcel Duchamp, explored conceptual art.

What artistic techniques did Dadaists use?

Dadaists used innovative and rebellious techniques, including collage, where they combined random images; photomontage, layering photos to create new meanings; ready-mades, everyday objects presented as art; and sound poetry, which deconstructed language into pure sounds. Performance art was also crucial, with chaotic live events featuring nonsensical poetry, music, and spontaneous actions. Their work embraced chance, randomness, and anti-traditional approaches to creativity.

How did Dadaism influence later art movements?

Dadaism directly influenced Surrealism, which built upon its rejection of logic but introduced structured dreamlike themes. It also inspired Conceptual Art, Pop Art, and Performance Art, with artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol adopting Dadaist ideas. Many contemporary digital and experimental artists continue to embrace Dadaist principles of questioning authority and redefining artistic meaning.

Is Dadaism still relevant today?

Yes, Dadaism’s rebellious spirit remains influential in modern and contemporary art. The movement’s challenges to artistic conventions can be seen in Conceptual Art, internet memes, political satire, and digital art. Many artists and activists use Dadaist techniques, such as collage and absurd humor, to critique society, proving that Dadaism’s questioning of norms and institutions is still relevant in today’s world.