The Radical Spirit of Dadaism: Art as Revolution

What is Dadaism? The Birth of Artistic Anarchy

The Home of Dadaism emerged as a revolutionary artistic movement born from profound disgust for the social, political, and cultural values of its time. Far more than just an art style, Dada embraced a kaleidoscope of creative expression spanning art, music, poetry, theater, dance, and politics. It wasn’t merely an aesthetic choice—it was a philosophical rebellion against the established order.

The name “Dada” itself embodies the movement’s spirit of playful absurdity. In French, “dada” is a child’s word for hobbyhorse, selected through a delightfully random act. Historical accounts tell us that Romanian poet, essayist, and editor Tristan Tzara discovered the name by randomly inserting a paper knife into a German-French dictionary during a meeting at Hugo Ball’s legendary Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland in 1916. The group immediately embraced this nonsensical word as the perfect representation for their anti-aesthetic creations and provocative protest activities.

The Origins of Dada: Born from War’s Chaos

Dadaism flourished between 1916 and 1923, taking root in Europe amid the unprecedented horrors of World War I (1914-1918). The movement didn’t emerge from an art school or manifesto—it was born from trauma and disillusionment with the world’s senseless destruction.

The founders of Dadaism represented a diverse international coalition of creative minds. German writer Hugo Ball, Romanian poet Tristan Tzara, and Alsatian-born artist Jean Arp stood among the movement’s key architects, alongside other intellectuals who converged in Zurich. Switzerland’s neutrality during the war made it a refuge for these artists and thinkers fleeing the conflict that was tearing Europe apart.

What makes Dadaism particularly fascinating is its simultaneous development across continents. While establishing its European headquarters in Zurich in 1916, Dada concurrently took root in New York City and Paris. In America, the movement found champions in Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Francis Picabia—revolutionary artists who would forever transform our understanding of what art could be.

Notably, many of Dada’s pioneers were remarkably young, mostly in their early twenties—a generation whose formative years were shaped by unprecedented global violence. Their youth fueled the movement’s energy, irreverence, and willingness to demolish artistic conventions without reservation.

Dadaism’s Nihilistic Revolution: Challenging the Status Quo

The Geographical Heartbeat of Dada

While Dadaism sparked international interest, its nihilistic revolution primarily flourished in the cultural centers of France, Germany, and Switzerland between 1916 and 1923. These regions became the crucibles where Dada’s most provocative ideas and practices took shape, fundamentally altering the artistic landscape of early 20th century Europe.

Embracing Chaos: The Dadaist Philosophy

Dadaists deliberately embraced what society considered irrational and chaotic. Their approach wasn’t merely rebellious—it was a calculated rejection of the very foundations of Western civilization. By championing anarchy and cynicism, they systematically dismantled the established laws of beauty and social organization that had dominated artistic and cultural discourse for generations.

The movement’s underlying purpose was profoundly political. Dadaists aimed to undermine the rules and conventions of the ruling establishment—the very systems they believed had enabled the catastrophic World War I to unfold. Their rage wasn’t abstract; it was directed specifically at modern European society and its governing structures that had permitted such senseless bloodshed and destruction to occur.

Art as Protest: The Dadaist Approach

What distinguished Dadaism from other artistic movements was its weaponization of creativity. Writers, poets, painters, and performers transformed art into a powerful vehicle for protest, seizing any available public forum to challenge the prevailing ideologies of their time.

With unflinching determination, they mounted cultural attacks against rationalism, nationalism, materialism, and any other societal elements they perceived as contributing to the war’s devastation. Their performances, exhibitions, and publications didn’t just question artistic traditions—they confronted the very philosophical frameworks that had shaped European thought for centuries.

The Dadaists’ revolutionary approach represented more than artistic innovation; it embodied a fundamental questioning of how society should function and what values it should uphold. Through their deliberate irrationality, they sought to expose the deeper irrationality of a world that had descended into unprecedented violence despite its claims to reason and progress.

The Historical Evolution of Dadaism

Transcending Artistic Boundaries During Global Conflict

As previously noted, the Dadaism movement emerged during the barbaric devastation of World War I, with its influential figures scattered throughout Europe and the United States. What made Dadaism truly revolutionary was its refusal to be confined by traditional artistic categorizations. The movement’s proponents weren’t content to identify merely as artists, writers, dancers, or musicians—they actively worked to demolish the boundaries that had historically separated different forms of creative expression.

This deliberate blurring of artistic disciplines wasn’t accidental but strategic. Dadaists recognized that compartmentalized art forms mirrored the compartmentalized thinking that had led society into war. By creating works that defied categorization, they challenged not just artistic conventions but the broader social structures that maintained them.

Beyond Creation: Dadaism as Cultural Disruption

Unlike traditional artistic movements focused on creating aesthetically pleasing works, Dadaists pursued a more ambitious goal. They weren’t satisfied with merely producing art; they sought to influence every aspect of Western civilization, compelling society to participate in the revolutionary changes catalyzed by World War I.

The movement deliberately avoided writing books or painting pictures that society would admire. Instead, Dadaists aimed to provoke strong reactions through deliberately challenging works and performances. They transformed public forums into stages for their provocations, creating experiences designed to shock audiences out of complacency and force confrontation with uncomfortable realities.

The Lasting Impact on Modern Art

This revolutionary approach to creative expression fundamentally transformed the trajectory of twentieth-century art. Dadaism’s emphasis on provocation, its questioning of artistic boundaries, and its rejection of purely aesthetic concerns opened new possibilities for subsequent generations of artists.

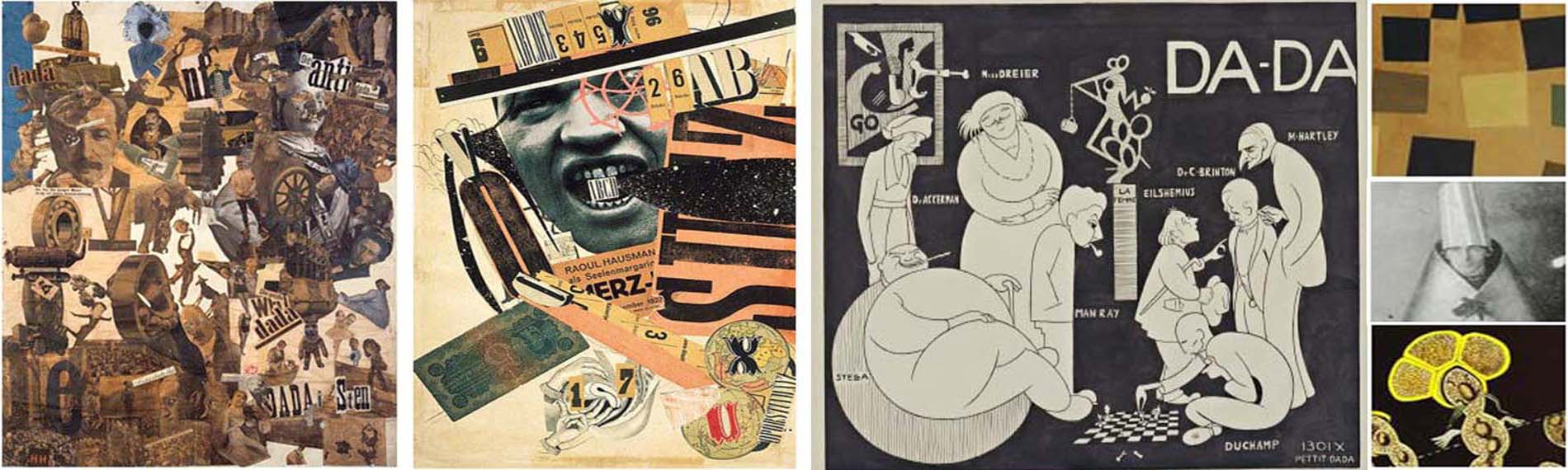

By challenging the very definition of what constitutes art, Dadaists laid the groundwork for conceptual art, performance art, installation art, and numerous other movements that would emerge throughout the 20th century. Their radical experiments with found objects, chance operations, photomontage, and nonsensical poetry established techniques that would become essential tools in the modern artist’s repertoire.

The movement’s influence extends beyond specific techniques to encompass broader attitudes about art’s purpose. Dadaism’s insistence that art should function as social commentary and political critique, rather than mere decoration, continues to resonate with contemporary artists engaging with pressing social issues.

The Foundation of Dadaism: Exile, Refuge, and Revolution

Zurich: The Birthplace of Dada’s Revolutionary Spirit

Founded in 1916 in Zurich, Switzerland, Dadaism emerged from a remarkable convergence of international exiles fleeing the devastation of World War I. This diverse group included pacifists, draft dodgers, political dissidents, and creative minds who found sanctuary in neutral Switzerland while conflict raged across Europe. Their shared outrage at the senseless bloodshed occurring on both sides of the continent fueled a revolutionary artistic movement that would challenge conventional thinking about art and society.

The Cabaret Voltaire: Dadaism’s Incubator

In February 1916, a watershed moment in art history occurred when Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Tristan Tzara, and their collaborators established the now-legendary Cabaret Voltaire. This unassuming nightclub in Zurich’s old town became the crucible where Dadaism’s provocative ideas first took form. The Dadaists outwardly presented the Cabaret as a venue dedicated to exploring artistic and cultural ideals through variety shows, but its actual purpose was far more revolutionary.

Just months after its founding, the group adopted the name “Dada”—a nonsensical term that perfectly captured their rejection of conventional meaning and rational discourse. This seemingly simple naming decision represented their first act of artistic defiance against a world they perceived as having lost its sanity.

Weapons of Artistic Revolution

The early Dadaists dedicated themselves to dismantling the cultural values and moral frameworks they believed had enabled the war’s devastation. Their strategy was brilliantly subversive—they appropriated the very forms of modern art as weapons to attack societal conventions.

Their arsenal included techniques that would later become fundamental to modern art: abstraction, collage, chance operations, audience confrontation, sound poetry, visual poetry, and experimental typography. By deploying these methods in deliberately provocative ways, they undermined traditional expectations about what art should be and how it should function.

Performance as Provocation

The Cabaret Voltaire and similar venues that sprouted across Europe became stages for Dadaist performances that shocked, bewildered, and challenged audiences. These presentations incorporated elements from various avant-garde movements sweeping through Europe, including Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism, but reconfigured them with distinctly Dadaist sensibilities.

Performance highlights included the simultaneous recitation of poems in multiple languages—German, French, and English—creating a cacophony that mirrored the chaotic state of wartime Europe. Hugo Ball famously appeared in bizarre cardboard costumes while chanting nonsensical sound poetry, deliberately abandoning linguistic meaning to explore pure sound. Meanwhile, Richard Huelsenbeck punctuated these performances with relentless drumbeats, creating an atmosphere of tribal ritual that contrasted sharply with Europe’s claims to civilization.

These performances weren’t merely entertainment—they were calculated provocations designed to jolt audiences out of complacency and force confrontation with the contradictions and hypocrisies of European culture during wartime.

The Post-War Evolution of Dadaism: New Frontiers and Provocations

Dadaism’s Diaspora: From Zurich to European Capitals

After World War I ended, the ability to travel freely across the European continent was restored, prompting Dada members to disperse from their Swiss sanctuary. This diaspora wasn’t a dissolution but a strategic expansion that would amplify Dadaism’s influence across Europe. Berlin and Paris emerged as the movement’s new strongholds, with former Zurich Dadaists regrouping in these cultural capitals and adapting their revolutionary tactics to new environments.

Berlin Dada: Radicalization in a Fractured Society

In Berlin, the movement took on a distinctly political character under the leadership of Richard Huelsenbeck, who assembled a formidable collective of writers and artists committed to extending Dada’s provocative legacy. Their timing was impeccable—they arrived amid the collapse of the German Empire, which had plunged society into unprecedented disorder. This volatile climate provided fertile ground for Dadaism’s disruptive philosophy.

Berlin Dadaists embraced direct action with remarkable audacity, staging interventions designed to expose societal hypocrisies and challenge established institutions. They disrupted religious services at the Berlin Cathedral, distributed provocative manifestos through leaflets, and mounted demonstrations at the National Assembly in Weimar, the seat of Germany’s fragile new democracy.

These political actions were complemented by more traditional artistic expressions—theater performances, Cabaret shows, exhibitions, and lecture tours—all infused with Dadaism’s signature irreverence and confrontational approach. The Berlin branch of the movement developed photomontage as a particularly potent technique, creating jarring visual juxtapositions that critiqued politics, media, and consumer culture.

Regional Variations: Cologne and Hanover Dada

Dadaism’s influence extended beyond Berlin to other German cities, each developing distinctive approaches reflecting local conditions and the personalities of key figures. In Cologne, Jean Arp and Max Ernst established a movement (1919-1920) that, while less overtly political than its Berlin counterpart, maintained an equally uncompromising stance toward social and artistic conventions.

The Cologne Dadaists focused intensely on challenging aesthetic traditions and moral certainties through their art. They distributed printed materials featuring grotesque imagery and unexpected juxtapositions, embodying Dadaism’s rejection of conventional beauty and meaning. Their most notorious event occurred in May 1920, when they organized an exhibition so provocative it was rumored to contain pornographic material—resulting in police intervention that only amplified the group’s notoriety.

Meanwhile, in Hanover, Kurt Schwitters developed his own unique interpretation of Dadaism through his concept of “Merz”—a practice involving collages and assemblages constructed from urban debris and discarded materials. Though somewhat isolated from other Dadaist groups, Schwitters’ work represented one of the movement’s most significant artistic innovations, transforming everyday refuse into complex compositions that challenged distinctions between art and life.

These regional variations demonstrated Dadaism’s remarkable adaptability and its capacity to respond to different social and cultural contexts while maintaining its fundamental commitment to disruption and provocation.

Pioneers of Provocation: Key Figures in the Dadaist Movement

Marcel Duchamp: The Conceptual Revolutionary

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) stands as Dadaism’s most influential figure, whose radical ideas continue to shape contemporary art. Though his association with the movement was somewhat loose, his innovations—particularly the ready-made—embodied Dada’s rejection of artistic conventions and embrace of conceptual approaches.

Beyond his famous ready-mades, Duchamp created complex works that challenged artistic categorization. His “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)” (1915-1923) combined painting, sculpture, and conceptual elements into an enigmatic meditation on desire and mechanical processes. After seemingly abandoning art to play chess in the 1920s, Duchamp continued working in secret on “Étant donnés” (1946-1966), a mysterious diorama revealed only after his death.

Duchamp’s lasting significance lies in his transformation of art from a primarily visual experience to a conceptual one. His famous assertion that he wanted “to put art back in the service of the mind” anticipated conceptual art’s emergence decades later and continues to influence artistic practice today.

Hannah Höch: Pioneering Photomontage and Feminist Critique

Hannah Höch (1889-1978) emerged as one of Dadaism’s most innovative visual artists and a pioneering feminist voice. As the only female member of the Berlin Dada group, she developed photomontage into a powerful medium for social critique, particularly regarding gender roles and women’s place in modern society.

Höch’s work “Das schöne Mädchen (The Beautiful Girl)” (1920) juxtaposes images of female bodies with mechanical parts and consumer products, critiquing the objectification of women in advertising and mass media. Her series “From an Ethnographic Museum” combined images of Western women with tribal masks and artifacts, challenging both colonial perspectives and Western beauty standards.

Despite being marginalized even within the avant-garde (her male Dadaist colleagues often diminished her contributions), Höch created a substantial body of work spanning six decades. Her artistic innovations and feminist perspective have received increasing recognition in recent decades, cementing her position as a crucial figure in 20th-century art.

Kurt Schwitters: The Merz Revolution

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) developed his own distinctive branch of Dadaism through his concept of “Merz”—a term derived from a fragment of the German word “Kommerz” (commerce) that appeared in one of his early collages. Though somewhat isolated from other Dadaist groups, Schwitters created some of the movement’s most innovative works.

Schwitters’ collages and assemblages incorporated urban detritus—tram tickets, newspaper fragments, broken furniture—transforming these discarded materials into complex compositions that blurred boundaries between painting, sculpture, and found-object art. His “Merzbau” (1923-1937), an architectural environment constructed in his Hanover home, grew organically over years as he added new elements, creating a sculptural space that anticipated later installation art.

As a pioneering sound poet, Schwitters also created “Ursonate” (1922-1932), a 35-minute sound poem composed of non-lexical vocalizations arranged in sonata form. This work, which he performed throughout Europe, remains one of the most ambitious sound poetry compositions ever created.

Forced to flee Nazi Germany in 1937, Schwitters continued creating Merz works in exile, his practice evolving but maintaining its essential character of transformation and recombination. His innovative approach to materials and boundary-crossing between artistic disciplines continues to influence contemporary art practice.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Multi-dimensional Modernist

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943) stands as one of Dadaism’s most versatile artists, working fluidly across disciplines including painting, textiles, architecture, interior design, and performance. Her presence challenges the often male-dominated narrative of Dadaism, highlighting women’s crucial contributions to the movement.

Beginning her artistic career as a textile designer, Taeuber-Arp brought craft techniques into conversation with avant-garde art, challenging hierarchical distinctions between “fine” and “applied” arts. Her geometric abstractions, like “Vertical-Horizontal Composition” (1916), applied rigorous formal principles across media, from paintings to beadwork to tapestries.

As a dancer at Zurich’s Laban School and performer at Cabaret Voltaire, Taeuber-Arp embodied Dadaism’s interdisciplinary spirit. Photographs show her performing in abstract costumes she designed, her body becoming another medium for geometric experimentation. Her marionettes for the play “King Stag” (1917-1918) transformed traditional puppetry through modernist abstraction.

Later, Taeuber-Arp co-founded and edited the influential journal “Plastique/Plastic,” creating a platform for abstract art across Europe. Her tragic early death from carbon monoxide poisoning in 1943 cut short a remarkable career, but her legacy as a pioneer of geometric abstraction and interdisciplinary practice continues to grow, exemplified by her appearance on the Swiss 50-franc note—a rare honor for a female artist.

The Home Of Dadaism

Dadaism in Context: Artistic Relationships and Lasting Influence

From Reaction to Revolution: Dadaism’s Art Historical Context

Dadaism didn’t emerge in isolation but positioned itself deliberately within the artistic landscape of early 20th-century modernism. While commonly understood as a reaction against traditional artistic values, Dadaism’s relationship to other movements reveals a complex dialogue that shaped modern art’s evolution.

The movement arose partly as a direct response to Expressionism, which dominated German art before World War I. Where Expressionists sought to convey emotional truth through distortion and intense color, Dadaists rejected the very notion that art should express anything meaningful at all. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s emotionally charged street scenes and Wassily Kandinsky’s spiritual abstractions represented precisely the kind of earnest artistic search for meaning that Dadaists mocked through deliberate absurdity.

Simultaneously, Dadaism maintained a complex relationship with Futurism, the Italian avant-garde movement celebrating technology, speed, and violence. While Dadaists shared Futurists’ desire to demolish traditional culture, they rejected Futurism’s enthusiasm for war and nationalism. The Futurist leader F.T. Marinetti’s declaration that “war is the world’s only hygiene” represented exactly the kind of thinking Dadaists blamed for World War I’s devastation.

Constructivism, emerging in revolutionary Russia, shared Dadaism’s political engagement but approached it from the opposite direction. Where Dadaists embraced chaos and chance, Constructivists like El Lissitzky and Vladimir Tatlin pursued geometric precision and industrial materials to create art serving revolutionary society. Despite these differences, the movements influenced each other through publications and exhibitions, particularly in Berlin.

The Surrealist Transformation: From Dada to Dream

Dadaism’s most direct and significant influence manifested in Surrealism, which emerged as Dada’s energy began to wane in the early 1920s. Many prominent Dadaists, including André Breton, Max Ernst, and Man Ray, transitioned to become key Surrealist figures, transforming Dada’s nihilistic rebellion into a more structured exploration of the unconscious mind.

André Breton, who participated in Parisian Dada activities, published the “First Surrealist Manifesto” in 1924, officially launching the movement that would build upon Dadaism’s foundation. Where Dadaism had used chance operations to undermine rationality, Surrealists employed similar techniques to access unconscious creativity. Dadaist automatic writing evolved into Surrealist “psychic automatism,” while Dadaist photomontage influenced Surrealist explorations of dream imagery.

However, Surrealism departed from Dadaism in crucial ways. Surrealism embraced Freudian psychology and sought to reconcile dream and reality into “an absolute reality, a surreality.” This positive program contrasted with Dadaism’s primarily oppositional stance. Surrealists also established a more formal organization with Breton as its leader, moving away from Dadaism’s anarchic approach to group dynamics.

The Neo-Dada Revival and Pop Art Connection

After World War II, artists rediscovered Dadaism’s revolutionary potential during the 1950s and 1960s. The Neo-Dada movement, including figures like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, revived Dadaist strategies of incorporating everyday objects and chance operations into their work. Rauschenberg’s “Combines” echoed Kurt Schwitters’ Merz assemblages, while Johns’ paintings of flags and targets questioned representation in ways reminiscent of Duchamp.

Pop Art continued this engagement with Dadaist principles. Andy Warhol’s screen-printed celebrity portraits and consumer products extended the Dadaist critique of uniqueness and artistic aura, while his Factory production methods challenged traditional notions of artistic craftsmanship. Roy Lichtenstein’s comic-inspired paintings similarly questioned boundaries between high and low culture that Dadaists had first attacked.

Contemporary Resonance: Dadaism’s Ongoing Influence

Dadaism’s impact extends throughout contemporary art in ways both obvious and subtle. Fluxus artists of the 1960s and 1970s directly cited Dadaist influences in their performance events and multiples, with George Maciunas even describing Fluxus as “neo-Dada in music, theater, poetry, art.”

Conceptual art’s prioritization of idea over execution traces directly to Duchamp’s ready-mades. When Joseph Kosuth presented “One and Three Chairs” (1965)—consisting of a physical chair, a photograph of the chair, and a dictionary definition of “chair”—he extended Duchamp’s questioning of representation and artistic value.

Contemporary performance art owes a substantial debt to Dadaist provocations at Cabaret Voltaire, while installation art develops the immersive environments pioneered by Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau. Political art continues to employ photomontage techniques developed by Berlin Dadaists, now updated for the digital age.

Perhaps most fundamentally, Dadaism’s irreverent approach to art institutions and conventions permeates contemporary artistic practice. The readiness to question, provoke, and redefine art’s boundaries—central to Dadaism’s project—has become an essential aspect of artistic identity in the 21st century.

Engaging with Dadaism: Interactive Elements for Your Website

Virtual Dada Laboratory: Creative Tools for Visitors

Transform passive website visitors into active participants by incorporating interactive Dadaist creation tools that embody the movement’s experimental spirit. A “Dada Poetry Generator” would allow users to create their own chance-based poems following Tristan Tzara’s famous instructions. Visitors could input text (or use pre-loaded newspaper articles) that the generator would randomly cut up and rearrange into surprising new combinations, demonstrating Dadaism’s embrace of chance operations.

Complement this with a “Digital Photomontage Studio” where users can create their own Hannah Höch-inspired collages by dragging, cutting, and recombining pre-loaded images or uploading their own. This tool would not only entertain visitors but educate them about Dadaist techniques while fostering creativity.

For the musically inclined, a “Sound Poetry Composer” could allow experimentation with nonsensical vocalizations and abstract sounds, inspired by Hugo Ball’s performances. Users could record, layer, and manipulate sounds to create their own Dadaist audio compositions, experiencing firsthand how Dadaists liberated language from meaning.

Include a prominent gallery section where visitors can share their creations, fostering a community of modern Dada practitioners and extending the website’s reach through social sharing.

Immersive Timeline: Navigating Dadaism’s Evolution

Create an interactive chronology that transforms Dadaism’s complex history into an engaging visual journey. This timeline would allow visitors to explore the movement’s development from its Zurich origins through its expansion to Berlin, Paris, and New York, highlighting key events, artworks, and publications.

Each timeline entry should feature rich media content—images of artworks, audio clips of sound poetry, video recreations of performances, and excerpts from manifestos—creating a multisensory understanding of Dadaism’s evolution. Important contextual events like World War I and the German Revolution would be included to illustrate how historical circumstances shaped the movement.

Implement a filtering system allowing visitors to focus on specific aspects of Dadaism—artistic techniques, key figures, geographical centers, or related movements—customizing the timeline to their interests. This flexibility would make the timeline valuable for both casual browsers and serious researchers.

Dada World Map: Geographical Exploration

Develop an interactive map visualizing Dadaism’s global spread and highlighting its different regional manifestations. Visitors could explore major Dadaist centers—Zurich, Berlin, Cologne, Hanover, Paris, and New York—each revealing location-specific content when selected.

For each location, provide information about key artists, defining characteristics of the local Dadaist scene, important venues (like Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich or Café des Westens in Berlin), and representative artworks. Include historical photographs of these locations and, where possible, then-and-now comparisons showing what these sites look like today.

Connect these geographical points with lines illustrating how artists moved between centers, visualizing the movement’s diaspora after World War I and highlighting the international nature of the avant-garde. This feature would help visitors understand how ideas traveled and evolved as they moved between different cultural contexts.

Virtual Gallery: Experiencing Dadaist Art

Create a virtual exhibition space where visitors can experience Dadaist artworks in context rather than as isolated images. Organize this gallery thematically—ready-mades, photomontage, collage, Dada publications—with immersive 360-degree navigation allowing visitors to move through the space as they would a physical museum.

Each artwork should be accompanied by concise yet informative descriptions explaining its significance, creation technique, and historical context. Include audio commentary from art historians providing deeper analysis of selected key works, making expert interpretation accessible to general audiences.

For major works like Duchamp’s “Fountain” or Höch’s photomontages, implement augmented features allowing users to interact with the artwork—zooming in on details, seeing x-ray views revealing underlying structures, or accessing side-by-side comparisons with related works.

Feature periodic “special exhibitions” highlighting different aspects of Dadaism to encourage return visits. These could focus on specific artists, techniques, or themes, with new content and perspectives keeping the website fresh and engaging for regular visitors.