Understanding Two Revolutionary Art Movements

Common Misconceptions About Origin and Place

Most people mistakenly believe that both Dadaism Vs Surrealism developed primarily in Paris, when in fact these revolutionary art movements emerged in different time periods, locations, and social contexts. This common misconception obscures the distinct origins and purposes that defined each movement’s unique approach to challenging artistic conventions.

Dadaism: Born from War’s Disillusionment

Dadaism erupted during the chaos of World War I (1914-1918), born from profound disillusionment and a feeling of betrayal by the societal structures that had led to unprecedented bloodshed. In neutral Switzerland, far from the battlefields but close enough to feel their reverberations, a group of young artists, writers, and intellectuals gathered at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire in 1916. These cultural rebels—including Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp, and Richard Huelsenbeck—positioned themselves in direct opposition to the mainstream artistic traditions they felt had failed humanity.

Anti-Art as a Revolutionary Statement

The Dadaists deliberately set themselves against using or creating “art for art’s sake” in conventional forms. Instead, they prioritized conveying powerful messages through their work, regardless of how their art was perceived by traditional critics or audiences. Their provocative approach was intentionally shocking, designed to wake society from what they saw as its dangerous complacency.

Breaking Boundaries, Not Abandoning Art

Far from being fundamentally against the concept of art itself, these Dada artists strived to discover innovative approaches to artistic expression. They experimented with new techniques that would later evolve into performance art, multimedia installations, and conceptual practices that transcended established boundaries. Their willingness to break taboos and ignore conventions opened entirely new possibilities for creative expression.

Surrealism: The Structured Dream Emerges

Surrealism, by contrast, emerged later in the post-war period of the 1920s, primarily centered in Paris under the leadership of André Breton. While Dada was a reaction against the rationality that had led to war, Surrealism developed as a more structured, though still revolutionary, exploration of the unconscious mind, dreams, and desire. Breton, who had initially participated in Dada activities, published the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, marking the formal transition from one movement to the next.

Two Paths of Artistic Revolution

This crucial distinction in timing and focus reveals why comparing Dadaism and Surrealism offers such valuable insights into the evolution of modern art. While both movements rejected conventional artistic values, they did so with different intentions, techniques, and philosophical foundations that would permanently alter the landscape of 20th-century creative expression.

The Paradox of Leadership: Organization Within Chaos

Dadaism’s Leaderless Revolution

In reality, Dada art positioned itself so fundamentally against the mainstream that it created a fascinating paradox: how could an anti-art movement have pioneers when the very concept of artistic leadership contradicted its core philosophy? By definition, a movement that declared itself “anti-art” resisted the traditional structures of artistic movements, including recognized figureheads and established techniques.

While prominent voices emerged within Dadaism—Tristan Tzara in Zurich, Richard Huelsenbeck in Berlin, Marcel Duchamp in New York—no single individual could claim to be the definitive voice of the movement. This wasn’t merely incidental but intentional—if Dadaism had allowed itself to be precisely defined under one leader’s vision, wouldn’t it simply become another conventional art form, contradicting its revolutionary purpose?

Unified Only in Their Rebellion

What makes Dadaism particularly unique among art movements was its lack of a unifying aesthetic direction, style, or technique. Unlike Impressionism with its distinctive brushwork or Cubism with its geometric deconstruction of form, Dada’s only consistent feature was its spirit of protest and its self-identification as “anti-art.” Beyond this shared rebellious attitude, the movement embraced a remarkable diversity of approaches.

This individualistic nature wasn’t a weakness but a deliberate strategy encapsulated in the motto “every individual for themselves.” Dadaists like Hans Arp created chance-based collages, Hannah Höch developed politically charged photomontages, Marcel Duchamp presented provocative readymades, and Hugo Ball performed nonsensical sound poetry—all vastly different expressions unified only by their rejection of artistic conventions.

Geographic Dispersion and Evolution

When Dada practitioners scattered across Europe after World War I ended in 1918, the movement’s decentralized nature became even more pronounced. Each center of Dada activity—Zurich, Berlin, Cologne, Hannover, Paris, and New York—developed its own character without a dominating leader to maintain cohesion. Berlin Dada became more politically engaged, while New York Dada embraced a more intellectual, ironic approach.

This lack of centralized leadership contributed significantly to why Dadaism, as a formal movement, dissolved after only a few years. Rather than disappearing, however, Dada’s revolutionary energy evolved into various new directions, most notably Surrealism but also influencing Constructivism, Abstract Expressionism, and later conceptual art.

Surrealism’s Structured Approach Under Breton

In stark contrast to Dadaism’s intentional chaos, Surrealism emerged with a clear leader in André Breton, who had participated in Paris Dada activities before breaking away to establish a more structured movement. Breton’s publication of the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924 marked a fundamental departure from Dada’s approach by providing a coherent philosophy centered on accessing the unconscious mind.

As Surrealism’s self-appointed “Pope,” Breton exercised considerable authority over the movement’s direction, even excommunicating artists who deviated from his vision. Under his leadership, Surrealism developed consistent theoretical foundations based heavily on Freudian psychoanalysis, with techniques like automatic writing and dream analysis providing methodical approaches to artistic creation—a significant departure from Dada’s embrace of chance and absurdity.

Two Models of Artistic Revolution

This fundamental difference in organization—Dadaism’s leaderless anarchy versus Surrealism’s structured hierarchy under Breton—reveals much about each movement’s nature and legacy. Dadaism’s brief, explosive existence embraced contradiction and resisted codification, allowing it to remain permanently revolutionary. Surrealism’s more organized approach under Breton’s leadership enabled it to develop a coherent body of work and theory that sustained the movement for decades.

These contrasting models of artistic revolution offer valuable insights into how avant-garde movements operate: one rejecting all structure to maintain its radical edge, the other building theoretical frameworks to extend its influence. Both approaches proved powerful in challenging artistic conventions, though in markedly different ways.#

Geographic Cohesion vs. Fragmentation: How Location Shaped Each Movement

Surrealism’s Centralized Parisian Base

Surrealism’s ability to operate under centralized leadership was made possible largely because the movement remained concentrated in Paris, unlike Dadaism’s scattered international presence. This geographic cohesion allowed André Breton to maintain direct influence over the movement’s participants, publications, and exhibitions. While Dada cells operated independently across different cities and continents with minimal coordination, Surrealists could gather regularly at Parisian cafés, studios, and galleries, ensuring consistent communication and ideological alignment.

Breton exercised remarkably strong control for the leader of an avant-garde movement, famously excommunicating members who deviated from his vision or disappointed his expectations. Despite what might appear as authoritarian tendencies, his firm leadership provided Surrealism with something Dada deliberately avoided: a coherent theoretical framework that could evolve systematically. Under his guidance, Surrealism maintained its core identity for approximately twenty-five years—an extraordinarily long lifespan compared to most avant-garde movements, including Dada’s brief but explosive existence.

Post-War Context: Different Responses to Trauma

The profound difference between Dadaism and Surrealism cannot be understood without considering their relationship to World War I. Surrealism emerged during the decade of relative peace and prosperity that followed the war, when European society was attempting to recover and rebuild. The deep wounds left by the conflict were addressed in contradictory ways—simultaneously ignored (as evidenced by the neglect of surviving veterans) and commemorated (through numerous monuments)—creating a cultural atmosphere of ambivalent remembrance.

In this context, Surrealism represented a psychological retreat by survivors unwilling to directly confront recent traumatic history. Rather than addressing the war’s political and social implications head-on as Dadaists had done, Surrealist artists, writers, and visual creators sought what the poet Guillaume Apollinaire (who coined the term “surrealism” in 1917) called “sur-reality”—a perspective that existed both outside and beyond perceived reality.

Inward vs. Outward Focus: Private Dreams vs. Public Protest

This fundamental difference in orientation reveals perhaps the most significant distinction between these movements. Dada was explicitly outward-facing, reality-based, and overtly political. Its public performances, manifestos, and provocations directly confronted societal values and institutions. Dadaists shouted their dissent through deliberate provocation and absurdist public interventions.

Surrealism, by contrast, turned inward toward a private exploration of the unconscious mind. Its introspective approach could be interpreted as therapeutic, replacing Dada’s aggressive public voice with a more subtle investigation of dreams, desires, and psychological states. While Dada attacked the rational structures that had led to war, Surrealism sought to bypass them entirely by accessing parts of human experience untouched by rational thought.

From Opposition to Theory: A Shift in Revolutionary Approach

This shift reflects Surrealism’s movement away from Dada’s oppositional stance toward a more theoretical position. Where Dadaists rejected established theories and systems outright, Surrealists developed their own alternative framework based largely on Freudian psychoanalysis. Techniques like automatic writing, dream recording, and creative games became systematic methods for accessing the unconscious—a far cry from Dada’s embrace of chance and anarchic disruption.

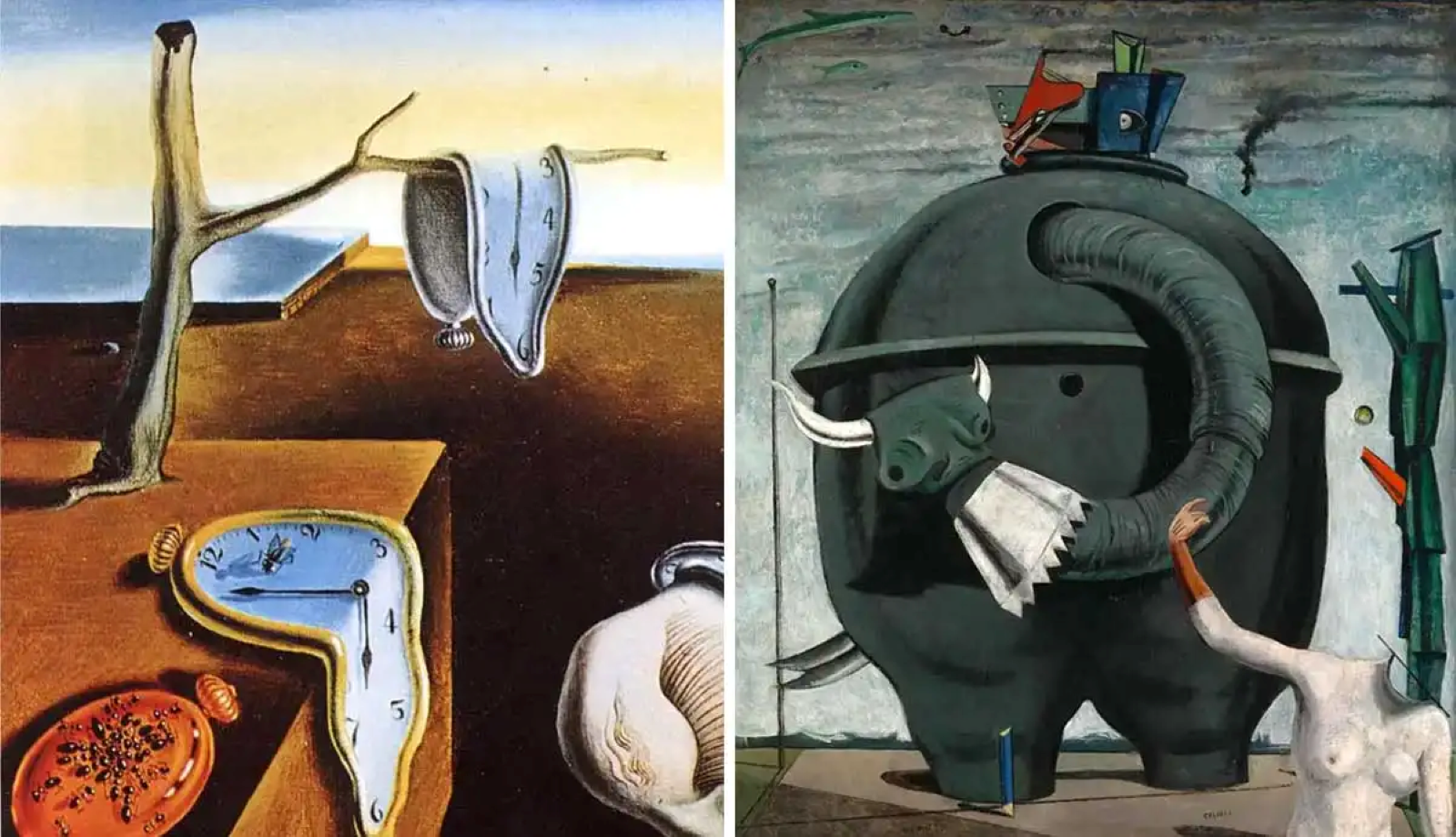

Salvador Dalí’s meticulously rendered dreamscapes, René Magritte’s precisely painted impossible scenarios, and Max Ernst’s frottage technique all demonstrate how Surrealism channeled irrational content through controlled, often technically accomplished execution—another stark contrast with Dada’s often deliberately crude or random production methods.

Two Responses to Modern Crisis

These contrasting approaches—Dada’s direct confrontation versus Surrealism’s psychological exploration—represent two distinct responses to modern crisis. Dada emerged during wartime as an immediate, outraged reaction against the systems that had failed humanity. Surrealism developed afterward as a more measured attempt to rebuild a new form of understanding from the psychological rubble. Both challenged conventional reality, but while Dada attacked it head-on through public provocation, Surrealism sought to transcend it through exploring the mind’s hidden dimensions.

Philosophical Foundations: Order vs. Chaos in the Mind

Freudian Influence: The Unconscious as Artistic Territory

Sigmund Freud’s revolutionary theories about the human mind provided a crucial foundation for Surrealism that was largely absent from Dadaism. Freud proposed that human thoughts and personality were divided into conscious and unconscious elements, which together formed our identity through the interplay of the id, ego, and superego. While these ideas circulated in intellectual circles during Dada’s emergence, they became central to Surrealism’s entire artistic approach.

Surrealists deliberately embraced Freudian psychoanalysis as a theoretical framework, believing that the liberal expression of one’s individual unconscious created art that embodied Freud’s theories of mind. André Breton, himself trained in psychiatry, was particularly fascinated by Freud’s interpretation of dreams and techniques for accessing unconscious material. This intellectual foundation gave Surrealism a coherent purpose that Dada, with its embrace of nihilism and rejection of systems, intentionally avoided.

Seeking Order vs. Celebrating Disorder

This fundamental difference in psychological approach reveals a profound distinction between the movements. Typical Surrealist works attempt to find order and meaning within the human unconscious, seeking to map its territory and reveal its hidden structures. Salvador Dalí’s precisely rendered but impossible dreamscapes, with their melting watches and elongated forms, represent attempts to visualize unconscious processes with paradoxical clarity.

Dadaism, by contrast, celebrated disorder and rejected the very notion that coherent meaning could or should be extracted from art. Where Surrealists sought to explore the unconscious systematically, Dadaists embraced nonsense and randomness as appropriate responses to a world whose supposed rationality had led to mechanized slaughter. This embrace of chaos wasn’t merely stylistic but philosophical—a rejection of the orderly systems that had failed humanity.

Creative Freedom vs. Theoretical Framework

It is debatable whether Dada or Surrealism represents the “better” art form—such judgments inevitably reflect subjective criteria—but their different approaches to creative freedom deserve examination. Dada artists often demonstrated greater imaginative range precisely because they weren’t bound by Freudian thinking or any other systematic framework. Many prominent Dadaists worked across multiple media and techniques without concern for consistency, embracing the complete freedom of expression that came from Dada’s acceptance of virtually anything as potential art.

Paradoxically, some artists who later became associated with Surrealism—Paul Delvaux, Salvador Dalí, and René Magritte among them—had previously painted in more conventional styles. While their technical proficiency remained evident in their Surrealist works, one could argue that by limiting themselves to Surrealism’s more defined parameters, they sacrificed some of the radical authenticity that characterized Dada’s boundless experimentation.

Two Approaches to Chance: Complete Surrender vs. Controlled Accident

Both movements notably engaged with chance operations, but in markedly different ways that reflect their core philosophies. Dada’s utilization of chance was radical and complete—a full surrender of artistic control to random processes. Whether tossing pieces of paper to create compositions (as in Hans Arp’s collages), cutting up newspapers to generate poetry (as in Tristan Tzara’s word experiments), or selecting objects blindly for assemblages, Dadaists embraced anarchic methods that deliberately undermined traditional notions of artistic intention and skill.

Surrealists, by contrast, approached chance from a more controlled position. Their methods—such as automatic writing, where the hand moves without conscious direction, or the “exquisite corpse” game, where artists collectively create works without seeing each other’s contributions—incorporated randomness within established frameworks. The resulting “accidents” were valued not for their pure randomness but as methods for accessing unconscious material that could then be interpreted and refined.

The Spectrum of Artistic Control

These contrasting relationships with chance operations reveal a fundamental difference in how each movement understood the artist’s role. Dada’s radical surrender to randomness represented a complete rejection of the Western artistic tradition that placed the genius creator at its center. By abandoning control, Dadaists challenged the very notion of artistic authority.

Surrealists maintained a more traditional view of the artist as interpreter and mediator of experience, even if that experience included unconscious elements. Their use of chance was ultimately in service of accessing material that the conscious mind would then organize into meaningful expressions—preserving the artist’s role as the final authority over the work, even when the source material emerged from uncontrolled processes.

The Quest for Meaning: Fundamental Philosophical Divides

Automatic Creation: Different Paths to Spontaneity

The Surrealist artists methodically pursued new techniques for creating “automatically,” circumventing conscious control to access the unfiltered content of the mind. Unlike Dada’s embrace of randomness for its own sake, Surrealists developed structured approaches to spontaneity, including automatic writing, frottage (rubbing surfaces to create textural patterns), and collaborative creation games. These methods weren’t merely stylistic innovations but disciplined attempts to access what they believed was hidden wisdom within the unconscious mind.

Surrealists also pioneered methods for generating new images and ideas through collective imagination. The famous “exquisite corpse” technique, where multiple artists would collaborate on a drawing without seeing each other’s contributions, exemplified their belief that group consciousness could reveal truths inaccessible to the individual mind. This collaborative approach stood in contrast to Dada’s more individualistic expressions, reflecting Surrealism’s more cohesive group identity.

Juxtaposition With Purpose vs. Undermining Meaning

While both movements frequently employed techniques of juxtaposition and unexpected combinations, their intentions differed dramatically. Dada photomontage artists like Hannah Höch and John Heartfield might place one randomly found image beside another, but their purpose was explicitly to undermine conventional meaning. These jarring combinations served to expose the absurdity of societal norms and expectations, deliberately creating cognitive dissonance that rejected the possibility of coherent interpretation.

Surrealism, by contrast, actively sought new meaning, alternative meaning, unexpected meaning—what could be called “sur-real” meaning that transcended ordinary reality. When René Magritte painted a pipe with the caption “This is not a pipe” or Salvador Dalí placed a soft watch in a desert landscape, they weren’t rejecting meaning but inviting viewers to discover deeper significances beyond conventional understanding. These works challenged perception while still affirming that interpretation and meaning-making were valuable pursuits.

The Essential Divide: Nihilism vs. Discovery

Here we find the crucial philosophical distinction that separates Dada from Surrealism at their cores. For Dadaists, responding to a world shattered by mechanized warfare and nationalist fervor, life ultimately had no inherent meaning, purpose, reason, or logic. Their works embraced this nihilistic vision not as a cause for despair but as a liberation from false systems that had led humanity to catastrophe. By rejecting meaning itself, Dada created space for radical freedom outside conventional frameworks.

For Surrealists, by contrast, life did have meaning—it simply required new methods to discover its hidden logic. They believed that by unlocking the visual and verbal codes buried in the chambers of the unconscious mind, one could encounter what Freud called the “uncanny”—the strangely familiar, the familiar made strange. This encounter with the uncanny wasn’t meant to destroy meaning but to expand it beyond the limitations of conscious rationality.

From Destruction to Reconstruction

This fundamental difference in philosophical orientation explains why Surrealism outlived Dada as a coherent movement. Dada’s purpose was essentially destructive—necessary and even liberating destruction, but destruction nonetheless. It sought to tear down false certainties and expose the bankruptcy of conventional meaning systems. Once this demolition was accomplished, Dada had fulfilled its purpose, leaving space for new approaches.

Surrealism offered one such approach—a reconstructive project that built upon Dada’s cleared ground. Rather than simply continuing the work of demolition, Surrealists proposed an alternative system for understanding human experience that acknowledged the limitations of rationality while still affirming that meaning could be found through new methods of exploration. This constructive orientation gave Surrealism a sustainability that Dada’s purely destructive approach couldn’t maintain.

Two Responses to Modern Crisis

These contrasting approaches—Dada’s embrace of meaninglessness versus Surrealism’s search for alternative meaning—represent two valid responses to the crisis of modernity that both movements confronted. Dada’s radical rejection of systems that had failed humanity offered necessary catharsis and created space for reimagining human experience from scratch. Surrealism’s exploration of the unconscious proposed a specific direction for that reimagining, suggesting that meaning could be recovered through accessing parts of the human mind that rational civilization had suppressed.

Together, these movements represent complementary phases of a profound cultural reckoning—Dada clearing away false certainties, Surrealism exploring new possibilities for meaning in their absence. Their differences weren’t merely aesthetic but reflected fundamentally different philosophical positions on whether meaning itself remained possible in the modern world.

Seeing the Difference: A Visual Comparison

The Readymade vs. The Dreamscape

Looking at Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain” (1917) alongside Salvador Dalí’s “The Persistence of Memory” (1931) reveals the fundamental visual difference between these movements at a glance. Duchamp’s porcelain urinal, simply turned upside down and signed “R. Mutt,” makes no attempt at aesthetic beauty. It’s an ordinary object, provocatively placed in an art context to challenge the very definition of art. The message is clear: anything can be art if the artist declares it so, and traditional notions of craftsmanship are irrelevant.

Dalí’s melting watches, by contrast, are meticulously painted in a technically accomplished style that recalls Renaissance precision. Despite their impossible forms, they’re rendered with photographic detail. This juxtaposition of dreamlike content with realistic technique exemplifies Surrealism’s approach: using traditional artistic skill to access nontraditional content from the unconscious. Where Dada disrupted through the ordinary presented as extraordinary, Surrealism disrupted through the extraordinary presented as ordinary.

Collage with Different Intentions

Hannah Höch’s Dada photomontage “Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany” (1919-20) uses fragmented images from mass media to create visual chaos that mirrors the political disruption of post-war Germany. The work deliberately rejects harmonious composition, embracing visual discord as social commentary. Images of politicians and celebrities are juxtaposed with machinery and text in a deliberately jarring arrangement.

Max Ernst’s surrealist collage novel “Une Semaine de Bonté” (1934), while also using found images, combines them seamlessly to create impossible but coherent dream narratives. His Victorian engravings merge into fantastical scenes that appear almost plausible despite their impossibility. Where Höch’s collage wants you to see the cutting and pasting as part of its political message, Ernst’s collage wants you to temporarily believe in its alternative reality.

The Toolbox: Techniques That Defined Each Movement

Dada’s Arsenal of Disruption

Dadaists developed techniques specifically designed to undermine artistic conventions and challenge bourgeois values:

Readymades elevated ordinary objects to art status through selection and context rather than creation, directly attacking the notion that art required skill or craft. Beyond Duchamp’s infamous urinal, objects like bottle racks and snow shovels became provocations simply through their placement in galleries.

Chance operations eliminated artistic control, allowing random processes to determine compositions. Hans Arp created collages by dropping torn paper pieces onto a surface and gluing them where they fell, while Tristan Tzara pulled words randomly from a hat to create poetry.

Sound poetry broke language down into pure phonetics divorced from meaning. Hugo Ball’s performances at Cabaret Voltaire featured nonsensical sound combinations recited while wearing bizarre costumes, deliberately discarding linguistic coherence.

Surrealism’s Methods of Exploration

Surrealists developed techniques aimed at accessing unconscious material while maintaining artistic control over its presentation:

Automatic writing involved writing rapidly without conscious intervention, allowing unconscious thoughts to emerge unfiltered. André Breton and Philippe Soupault’s “The Magnetic Fields” (1920) pioneered this technique that became central to Surrealist practice.

Paranoid-critical method, developed by Salvador Dalí, involved cultivating paranoid states to perceive multiple images within single forms—seeing, for example, a sleeping dog, a landscape, and a face all within the same visual configuration.

Frottage, perfected by Max Ernst, involved rubbing pencil on paper placed over textured surfaces, using the resulting patterns as starting points for developing images—a technique for prompting the imagination through semi-random means.

While Dada techniques served primarily to disrupt conventional meaning, Surrealist techniques aimed to discover new meaning hidden within the unconscious mind. This fundamental difference in purpose guided how each movement developed and applied their distinctive artistic methods.

Art and Politics: Different Modes of Resistance

Dada’s Direct Confrontation

Dada emerged as an explicitly political response to World War I, positioning itself in direct opposition to the nationalism, rationalism, and bourgeois values that Dadaists believed had led to mechanized slaughter. In Zurich, this opposition took the form of provocative performances and publications that mocked patriotic sentiment. But it was in Berlin where Dada’s political edge became most pronounced.

Berlin Dadaists like George Grosz, John Heartfield, and Hannah Höch created biting visual critiques of Weimar Germany’s political establishment. Heartfield pioneered photomontage as political weapon, creating images that exposed the contradictions of capitalism and the rising threat of fascism. Grosz’s caricatures savagely depicted military officers, industrialists, and clergy as corrupt and grotesque. This wasn’t art about politics—it was art as politics.

Dada’s anti-nationalist stance directly challenged the patriotic fervor that had fueled the war. By declaring themselves citizens of art rather than of nations, Dadaists rejected the very foundation of nationalist ideology. This radical internationalism made them targets for right-wing hostility but also established a model for art that transcended national boundaries.

Surrealism’s Political Evolution

Surrealism’s relationship with politics evolved more gradually. Initially focused on psychological exploration rather than direct political engagement, the movement nevertheless developed explicit political dimensions under Breton’s leadership. By the late 1920s, many Surrealists, including Breton himself, had joined the French Communist Party, seeing revolutionary politics as complementary to their artistic revolution.

Unlike Dada’s anarchic approach, Surrealism attempted to reconcile its artistic practice with structured political theory. Breton’s “Second Surrealist Manifesto” (1929) explicitly aligned the movement with dialectical materialism, though this alliance proved unstable. When Surrealists refused to adopt Soviet-dictated “socialist realism,” tensions with orthodox Communists grew.

The Surrealists’ approach to fascism differed from Dada’s direct attacks. While artists like Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí created works with political implications, they often employed symbolic and psychological approaches rather than explicit critique. This indirect approach sometimes led to ambiguity—Dalí’s flirtation with fascist imagery complicated the movement’s political positioning.

Two Models of Artistic Resistance

These different approaches to politics reflect fundamental differences between the movements. Dada’s political engagement was immediate, direct, and rooted in the present moment—a tactical response to urgent crises. Surrealism’s politics were more strategic, theoretical, and oriented toward a reimagined future where revolutionary politics and psychological liberation would converge.

Both movements ultimately rejected the separation between art and politics, but they envisioned their relationship differently. For Dada, art became a weapon in immediate political struggles. For Surrealism, politics became one dimension of a broader project to transform human consciousness through accessing the unconscious mind.

From Rebellion to Movement: A Timeline of Evolution

The Birth and Spread of Artistic Revolution

1916: Dada emerges at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire, founded by Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings as a refuge for artists escaping World War I. The name “Dada” is allegedly chosen randomly from a dictionary, embodying the movement’s embrace of chance.

1917: Marcel Duchamp submits “Fountain” to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition in New York, where it’s rejected despite the “no jury” policy. This rejection only reinforces Dada’s critique of art world hypocrisy.

1918: The Berlin Dada group forms with a more explicitly political focus, responding to Germany’s post-war crisis with photomontage and provocative manifestos. Richard Huelsenbeck, George Grosz, and Hannah Höch become key figures.

1919-1921: Dada activities spread to Paris, where Tristan Tzara’s provocative performances attract a group of young poets and artists, including André Breton, Louis Aragon, and Philippe Soupault—future founders of Surrealism.

1922: Tensions develop between Tzara and Breton over Dada’s direction. Breton, increasingly interested in exploring the unconscious rather than simply provoking outrage, begins seeking more structured approaches to artistic rebellion.

1924: Breton publishes the First Surrealist Manifesto, formally establishing Surrealism as a distinct movement with roots in, but separate from, Dada. The manifesto defines Surrealism as “pure psychic automatism” aimed at expressing “the real functioning of thought.”

1925-1930: Period of transition and overlap, with many former Dadaists exploring Surrealist techniques while maintaining some Dadaist attitudes. Max Ernst, Man Ray, and Hans Arp successfully bridge both movements.

1930s: Surrealism expands internationally while developing a more coherent philosophy based on Freudian psychology. Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, and others create the iconic imagery now most associated with the movement.

1939-1945: World War II forces many Surrealists to flee Europe for the United States, spreading the movement’s influence to American art while fundamentally altering its European character.

1966: The last Surrealist exhibition in Paris signals the movement’s end as a cohesive force, though both Dada and Surrealism continue to influence countless artists to this day.

Iconic Works That Defined Each Movement

Dada’s Revolutionary Objects

Marcel Duchamp’s “L.H.O.O.Q.” (1919) epitomizes Dada’s irreverent approach to art history and conventional values. By adding a mustache and goatee to a postcard reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” and giving it a title that, when pronounced in French, sounds like “she has a hot ass,” Duchamp simultaneously mocks art reverence and gender norms. The work requires no technical skill, using simple defacement to transform Western culture’s most iconic painting into a joke.

Raoul Hausmann’s “Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Time)” (1920) presents a wooden hairdresser’s dummy with various measuring instruments and everyday objects attached—a ruler, pocket watch mechanism, typewriter parts. This assemblage satirizes the modern “man without a spirit,” whose head contains not thoughts but the measuring tools of rationalism and materialism. Unlike Surrealist objects that explore the unconscious, this Dada work directly criticizes social conditions.

Kurt Schwitters’ “Merz Picture 25A: The Star Picture” (1920) showcases a different side of Dada—less overtly political but equally revolutionary in form. Created from discarded materials including paper scraps, fabric, and wood, the work elevates trash to the status of fine art. Schwitters’ approach differs from both Duchamp’s readymades and Berlin Dada’s political photomontage, embodying Dada’s diversity of methods.

Surrealism’s Dream Visions

René Magritte’s “The Treachery of Images” (1929), with its realistic painting of a pipe captioned “This is not a pipe” (Ceci n’est pas une pipe), explores the gap between representation and reality. Unlike Dada works that attack meaning itself, Magritte’s painting invites philosophical reflection on the nature of images and language. Its paradox is presented with technical precision rather than chaotic juxtaposition.

Salvador Dalí’s “The Persistence of Memory” (1931) presents melting watches in a dreamlike landscape, creating one of Surrealism’s most recognizable images. The painting’s meticulous technique and strange imagery exemplify Surrealism’s blend of academic painting skill with unconscious content. Unlike Dada’s readymades, which required no traditional artistic ability, Dalí’s work showcases virtuosic technique in service of dreamlike vision.

Meret Oppenheim’s “Object (Breakfast in Fur)” (1936), a teacup, saucer, and spoon covered in gazelle fur, creates uncomfortable associations between the domestic ritual of tea drinking and unsettling sensuality. While it shares Dada’s use of everyday objects, its purpose isn’t to negate meaning but to explore psychological discomfort and desire. The work’s precisely controlled execution differs from Dada’s often rougher aesthetic approach.

From History to Now: Contemporary Relevance

Dada’s Digital Descendants

In today’s digital landscape, Dada’s influence appears in surprising places. Internet meme culture, with its rapid appropriation and transformation of existing images, operates remarkably like Dada collage. When users add absurdist captions to found images or deliberately degrade visuals through multiple compressions, they’re employing techniques that would be familiar to Hannah Höch or Raoul Hausmann.

Contemporary movements like culture jamming, which subverts commercial advertising to critique consumer culture, continue Dada’s tradition of disruption. When Adbusters modifies corporate logos or the Yes Men impersonate corporate representatives to expose hypocrisy, they’re following the Dadaist playbook of using absurdity to reveal deeper truths.

Conceptual art, which prioritizes ideas over technical execution, owes a profound debt to Duchamp’s readymades. When contemporary artists present everyday objects or situations as art, they’re working within a tradition that Dada established. The questions Duchamp raised about what constitutes art continue to animate contemporary artistic debates.

Surrealism’s Cultural Infiltration

While Dada’s influence appears in specific art practices and activist strategies, Surrealism has permeated broader visual culture. Commercial advertising regularly employs surrealist techniques—impossible juxtapositions, dreamlike scenarios, and symbolic objects—to create memorable campaigns that bypass rational resistance to their messages.

Cinema has perhaps been most profoundly influenced by Surrealist aesthetics. From David Lynch’s dreamlike narratives to Jordan Peele’s uncanny horror, filmmakers continue to draw on Surrealist approaches to access psychological states beyond ordinary consciousness. The term “surreal” has entered everyday language as a descriptor for strange, dreamlike experiences.

Digital tools have made Surrealist techniques more accessible than ever. Apps that generate AI art based on text prompts create surrealist juxtapositions with ease, while photo manipulation software allows anyone to create “impossible” images that would have required painstaking technique in Magritte’s day.

From Avant-Garde to Everyday

What’s most striking about both movements’ contemporary influence is how techniques that once shocked the art world have become integrated into mainstream visual culture. Dadaist collage and Surrealist juxtaposition now appear in advertising, entertainment, and everyday communication through social media.

This mainstreaming raises intriguing questions: Can techniques designed to challenge conventional thinking retain their revolutionary edge when they become conventional themselves? Or do these artistic approaches maintain some inherent power to disrupt regardless of context? The continuing resonance of both movements suggests that even in new contexts, their core insights about art, consciousness, and society retain their power to provoke and inspire.

The Women Who Shaped Both Movements

Dada’s Female Pioneers

Emmy Hennings co-founded the Cabaret Voltaire but remains often overlooked in Dada histories. Hannah Höch created groundbreaking political photomontages that specifically addressed gender politics. Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s multi-disciplinary work challenged the hierarchy between fine and applied arts. Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s radical performances and found-object sculptures embodied Dada’s spirit, with recent scholarship suggesting she may have conceived “Fountain.”

Surrealism’s Gender Paradox

While celebrating “woman” as muse and inspiration, Surrealism often marginalized actual women artists. Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Dorothea Tanning created dreamlike works exploring feminine experience. Meret Oppenheim’s “Object (Breakfast in Fur)” became iconic, but she struggled against being defined by this single piece. Frida Kahlo famously rejected Breton’s Surrealist label, stating “I never painted dreams, I painted my reality.”

Revolutionary Art, Traditional Gender Views

Despite their artistic radicalism, both movements largely maintained conventional gender hierarchies. Dada’s anarchic approach created some space for women’s participation but left gender bias largely unchallenged. Surrealism’s theoretical framework often reinforced views of women as mysterious “others” rather than creative equals.

Geographic Variations: Local Flavors of Rebellion

Dada’s Multiple Centers

Zurich: Neutral Switzerland fostered international performance and abstraction at Cabaret Voltaire.

Berlin: Post-war crisis produced politically charged photomontage responding to Germany’s collapse.

New York: Distance from the European conflict created a cooler, more intellectual and ironic approach.

Paris: Literary traditions influenced its character, becoming the site where Dada evolved into Surrealism.

Surrealism Beyond Paris

Paris: Remained the administrative center under Breton, establishing theoretical foundations.

Belgium: Magritte and Delvaux developed meticulously rendered “magic realism” approaches.

Latin America: Connected with indigenous traditions and revolutionary politics, especially in Mexico.

Britain: Maintained closer ties to Romanticism and Gothic traditions, finding the uncanny in landscapes.

Local Expression, Global Movement

Dada’s decentralized structure allowed independent development of regional styles united by shared opposition to conventions. Surrealism’s more organized structure maintained greater theoretical consistency while still permitting local adaptations. Both movements demonstrated how revolutionary artistic concepts could transcend national boundaries while gaining new dimensions through local interpretation.

Dadaism Vs Surrealism

What is the main difference between Dadaism and Surrealism?

Dadaism was an anti-art movement that rejected logic, reason, and artistic norms, embracing absurdity, satire, and randomness. It was a response to the horrors of World War I, aiming to expose the meaninglessness of life through irrational and nonsensical works. Surrealism, emerging later, focused on unlocking the subconscious mind, drawing inspiration from dreams, fantasies, and irrational imagery. While Dadaism thrived on chaos and protest, Surrealism sought to create a deeper reality by blending fantasy with reality through techniques like automatic drawing and dream analysis.

How did Dadaism and Surrealism influence modern art?

Both movements significantly shaped contemporary art, but in different ways. Dadaism’s emphasis on anti-establishment ideas inspired conceptual and performance art, pushing boundaries in how art is perceived and created. It introduced techniques like collage, photomontage, and readymades, which remain influential today. Surrealism, on the other hand, influenced modern art through its dreamlike compositions and psychological depth. Abstract and fantasy-driven works in digital media, film, and photography owe much to Surrealist experimentation with automatic writing and free association. Together, they reshaped artistic freedom and creative exploration.

Were Dadaists and Surrealists politically motivated?

Dadaists were deeply political, using their art as a direct protest against war, nationalism, and societal structures. Many of their works mocked political leaders, capitalism, and the absurdity of authority. The movement sought to dismantle traditional power structures through chaos and unpredictability. Surrealists, while not as aggressively anti-political, aligned with leftist ideologies, particularly communism. They explored how unconscious desires shape human behavior and often used art to critique oppression, colonialism, and rigid social norms. Though their approaches differed, both movements shared a rebellious spirit against conformity and authoritarianism.

How did Dadaism and Surrealism influence other creative fields like literature and film?

Dadaism influenced literature through experimental poetry, nonsensical wordplay, and cut-up techniques, which later inspired beat poets and avant-garde writers. Its impact on film can be seen in abstract, experimental cinema that breaks narrative structures. Surrealism had a profound influence on literature and film, inspiring works that explore dreams, subconscious symbolism, and irrational storytelling. Writers like André Breton and filmmakers like Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí introduced surreal narratives that blurred reality and fantasy. Their impact continues in modern surrealist films, psychological thrillers, and unconventional storytelling.

Why do Dadaism and Surrealism remain relevant today?

Dadaism and Surrealism continue to shape contemporary art, media, and cultural movements. Dada’s rejection of traditional norms resonates in digital art, meme culture, and political protest art, where absurdity and satire remain powerful tools. Surrealism’s exploration of dreams and subconscious themes influences fashion, advertising, and visual media, making it a cornerstone of fantasy and abstract creativity. Both movements remind artists and thinkers that creativity thrives when norms are challenged, rules are broken, and imagination takes precedence over conformity. Their legacy lives on in modern art’s rebellious and thought-provoking spirit.

At a Glance: Dadaism vs Surrealism Comparison

| Feature | Dadaism | Surrealism |

|---|---|---|

| Time Period | 1916-1924 | 1924-1966 |

| Origins | Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire during WWI | Paris, evolved from Dada after WWI |

| Key Founders | Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Tristan Tzara | André Breton, former Dada participant |

| Leadership | Deliberately leaderless, anarchic | Centralized under Breton as “Pope” |

| Organization | Loosely connected international groups | More structured movement with manifestos |

| Primary Centers | Zurich, Berlin, New York, Paris | Paris, with international expansion |

| Philosophical Base | Nihilism, rejection of meaning | Freudian psychology, exploring unconscious |

| Attitude to Reality | Reality is meaningless, absurd | Reality is limited, unconscious holds truth |

| Main Purpose | Destroy artistic conventions | Discover new artistic possibilities |

| Political Stance | Direct anti-war, anti-nationalist protest | Evolved from psychological to political engagement |

| Approach to Art | “Anti-art,” rejecting beauty and skill | Using traditional techniques for non-traditional content |

| Use of Chance | Total surrender to randomness | Controlled methods to access unconscious |

| Key Techniques | Readymades, photomontage, sound poetry | Automatic writing, frottage, dreamlike juxtaposition |

| Relationship to Logic | Complete rejection of logic | Exploring alternative logic of dreams |

| Key Visual Artists | Duchamp, Höch, Heartfield, Schwitters | Dalí, Magritte, Ernst, Miró |

| Attitude to Tradition | Aggressive rejection | Transformation through unconscious |

| Legacy | Conceptual art, performance art, punk | Commercial design, fantasy art, cinema |

| Duration | Brief, explosive existence | Long-lasting, sustained movement |

| Tone | Deliberately provocative, angry, satirical | Mysterious, dreamlike, psychological |

| Famous Examples | Duchamp’s “Fountain,” Höch’s photomontages | Dalí’s melting watches, Magritte’s impossible scenes |