Dadaism: The Story of Art’s Most Rebellious Movement

The Revolutionary Spirit That Refuses to Die

Dadaism The Story – Artistic movements often fade into history textbooks, but Dadaism has proven remarkably resilient. Born in the chaos of the early 20th century amid the devastation of World War I, this radical anti-art movement continues to influence contemporary creators more than a century later. Unlike many historical art movements, Dada’s deliberate absurdity, political edge, and rejection of conventions speak powerfully to our own turbulent times.

From Wartime Revolt to Enduring Influence

Dadaism erupted as a direct response to a world gone mad. In 1916, as the mechanized slaughter of World War I reached its height, a group of exiled artists, writers, and intellectuals gathered at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire. United by their disgust with the nationalism and rationalism that had led to unprecedented bloodshed, they formed an artistic rebellion characterized by deliberate irrationality, provocation, and a profound questioning of all established values.

These early Dadaists—including Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Tristan Tzara, Hans Arp, and Marcel Janco—rejected the notion that art needed to be beautiful, rational, or even comprehensible. Instead, they embraced chance, nonsense, and found materials as tools for creating work that challenged bourgeois sensibilities and artistic conventions. Their performances, collages, sound poems, and manifestos deliberately shocked audiences, creating experiences that demolished traditional artistic expectations.

A Movement Built on Creative Cross-Pollination

Dadaism didn’t emerge from a vacuum. The movement drew inspiration from several avant-garde currents that had already begun to transform early 20th-century art, including Cubism’s fragmentation of form, Futurism’s embrace of technology and speed, Constructivism’s political engagement, and Expressionism’s emotional intensity. What made Dada distinctive was how it radicalized these influences, pushing them toward absurdity and political confrontation.

This ability to synthesize and transform influences helps explain why Dadaism itself has proven so adaptable. Contemporary artists continue to combine Dadaist techniques with newer approaches, creating work that addresses current social and political conditions while maintaining the movement’s rebellious spirit. Though these neo-Dadaist expressions may differ from the original movement in context and execution, they share its fundamental questioning of authority and convention.

Timeless Relevance in a World of Recurring Crises

What makes Dadaism particularly relevant today is how its core concerns continue to resonate. The movement’s mockery of materialism, criticism of blind nationalism, skepticism toward technological “progress,” and questioning of established moral codes speak directly to our contemporary predicaments. In a world still grappling with militarism, consumerism, technological disruption, and social fragmentation, Dada’s radical approach to art-making offers strategies for creative resistance and reimagination.

The Dadaists responded to their broken world by dismissing artistic conventions and seeking complete creative freedom. Their destructive impulse wasn’t merely negative but cleared space for new possibilities. As we examine the story of Dadaism—from its explosive beginnings to its ongoing influence—we discover not just a historical art movement, but a perpetually renewable source of artistic liberation and political engagement.

The Paradox of Definition: Capturing the Uncapturable

The Movement That Resists Classification

Dadaism as an artistic style presents a fundamental paradox: How do you define a movement explicitly created to defy definition? Unlike Impressionism with its distinctive brushwork or Cubism with its geometric fragmentation, Dada deliberately evades stylistic consistency. Unless artists actively identify themselves as Dadaists, their work often becomes subject to academic debate—labeled and relabeled as critics attempt to categorize what was designed to be uncategorizable.

This definitional challenge stems from Dada’s core purpose. Since the movement intended to stand in direct opposition to all norms of bourgeois culture, it could hardly support any fixed identity, even its own. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, Hannah Höch’s photomontages, Kurt Schwitters’ Merz constructions, and Hugo Ball’s sound poetry share a revolutionary spirit but little visual or technical consistency. This deliberate incoherence wasn’t a failing but a feature—Dada refused to become another easily digestible artistic “style.”

The Self-Destructing Art Movement

As Peter Fleming insightfully wrote in 2015:

“Dada was designed to be ghost-like and short-lived. An intransigent and inconsequential mockery of the vain conceit that cultural monuments stood for something immortal, something ever-lasting. Self-immolation was written into Dada’s very DNA, its main aesthetic tenant its brevity and self-destructiveness.”

Unlike movements that sought artistic immortality, Dada embraced its own ephemerality. This helps explain why “there are no world-renowned Dadaists on the scale of a Hemingway, or a Shostakovich, or a Picasso, and no Dadaist produced a particularly large body of work.” Several prominent Dadaists even ended their own lives, which Fleming provocatively characterizes as “the ultimate expression in Dadaist performance art”—though this simplifies the complex personal circumstances surrounding these tragedies.

The movement’s relative obscurity compared to other avant-garde developments is entirely consistent with its aims. As Fleming notes, “If you’ve never even heard of the movement, you’re hardly to be blamed—the Dadaists were simply there one day—like a wisp of smoke swirling briefly, illuminated by a moonbeam—and the next were gone.” This transience wasn’t failure but fulfillment: “Rarely do artistic movements fulfil their stated intentions so completely—Dada was a fully-realized, soulless expression of Dionysian excess. A howl of existential despair. And a casualty of war.”

The Neo-Dadaist’s Dilemma

Consider, then, the paradoxical position of contemporary artists who draw inspiration from Dadaist attitudes and techniques. How does one authentically channel a movement that rejected authenticity itself? How can artists create “Dadaist” work when the very act of labeling it contradicts Dada’s anti-label ethos?

This tension produces fascinating creative responses. Some contemporary artists embrace contradiction, explicitly referencing Dadaist techniques while acknowledging the impossibility of truly reviving the movement. Others adopt Dada’s methods without claiming the name, focusing on its disruptive spirit rather than its historical specificity. Still others use digital technologies to create new forms of chance-based creation, absurdist juxtaposition, and institutional critique that Dadaists might have employed had they lived in our era.

What unites these neo-Dadaist approaches isn’t visual similarity but a shared commitment to questioning conventions, embracing chance, and challenging institutional authority. The movement’s resistance to definition becomes its most enduring legacy—a perpetual invitation to creative rebellion that can never be fully exhausted precisely because it can never be fully defined.

The Echo of Rebellion: Dadaism’s Enduring Legacy

Beyond Art: Dada’s Cultural Revolution

What many people fail to recognize is the profound artistic legacy that Dadaists have imprinted on the very structure of the art world and beyond. Their influence extends far beyond museums and galleries, permeating contemporary culture in ways both obvious and subtle. While direct homages exist—such as Yoko Ono’s reappropriation of Duchamp’s iconic urinal—Dada’s most significant impact lies in how its core principles have filtered through societal values to become, in essence, a way of life.

This cultural permeation can be observed in the performances of contemporary pop icons like Madonna and Lady Gaga, whose massive popularity stems partly from their willingness to embrace elements outside conventional norms. When Lady Gaga appears in a dress made of raw meat or when Madonna incorporates provocative religious imagery into her performances, they channel Dada’s spirit of deliberately disrupting expectations and challenging social boundaries. These aren’t mere publicity stunts but contemporary expressions of the Dadaist impulse to shock audiences into new awareness.

Beyond individual artists, Dada’s DNA can be detected in phenomena like viral internet memes, guerrilla marketing campaigns, and reality-bending digital filters. Each employs Dadaist techniques of juxtaposition, absurdity, and context disruption to create meaning through unexpected combinations. When seemingly random images gain significance through mass sharing and modification, or when advertisers deliberately create surreal scenarios to capture attention, they’re drawing from the Dadaist playbook, whether consciously or not.

The Revolutionary Impulse: Freedom Through Destruction

Having absorbed Italian Futurist Filippo Marinetti’s confrontational approach and attack upon established artistic and social conventions, Dada emerged as a profoundly liberating movement that continues to inspire innovation and rebellion across creative disciplines. Though Dada was born as a protest against war, its destructive and exhibitionist activities became even more outrageous and influential after World War I concluded in 1918.

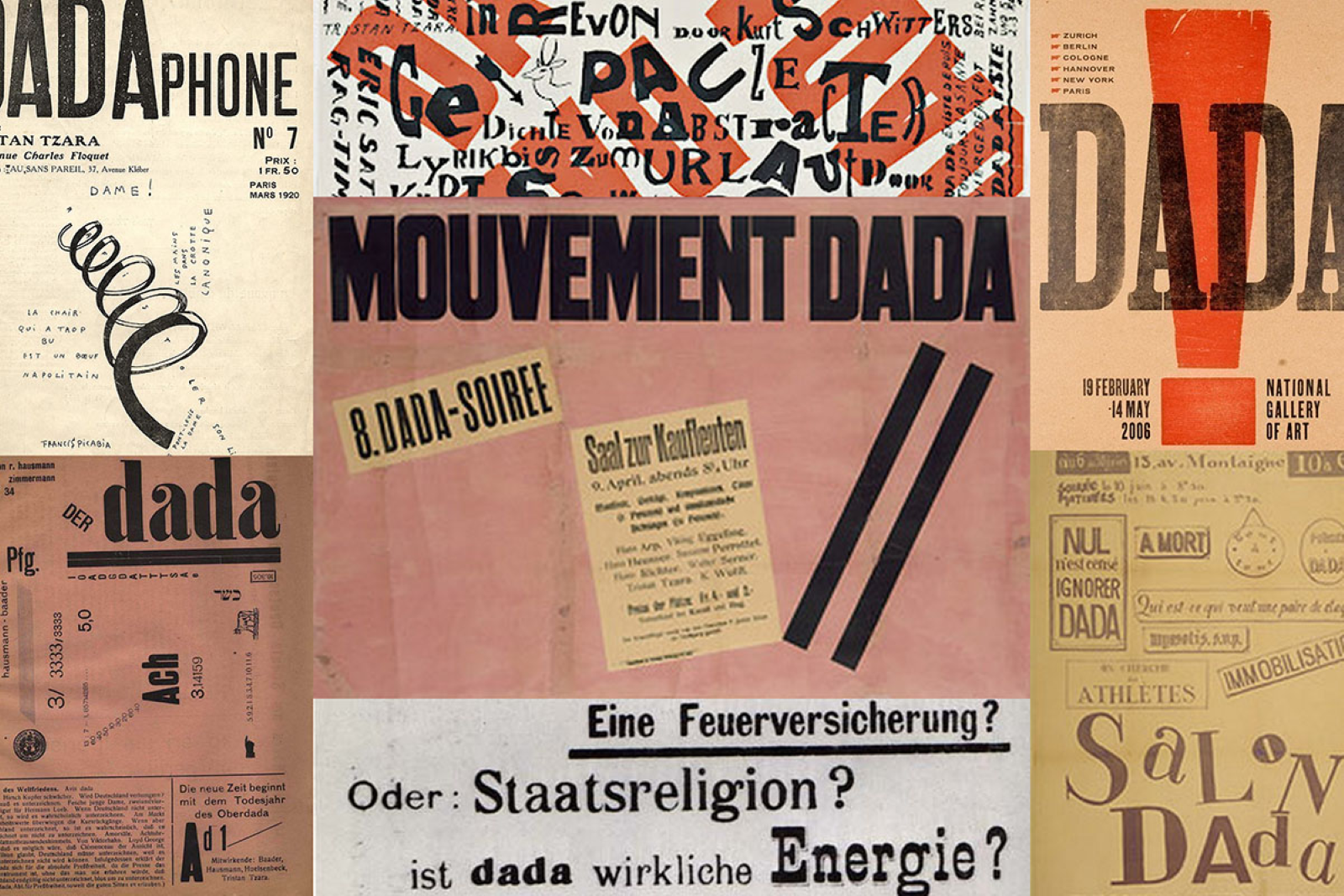

This intensification reflected the movement’s evolution from immediate crisis response to a more sustained critique of postwar society’s attempt to return to “normalcy.” Dadaists recognized that the social systems that had led to war remained largely intact, prompting them to escalate their provocations. Through performances, publications, exhibitions, and public interventions in cities like Zurich, Berlin, Cologne, Paris, and New York, they created an international network of artistic disruption that challenged audiences to question everything they had previously accepted without thought.

The movement’s techniques—readymades, photomontage, collage, sound poetry, and chance operations—provided practical tools for bypassing conventional thinking and accessing new creative territories. These approaches democratized artistic creation by emphasizing concept over technical skill, opening doors for future generations to engage with art-making regardless of traditional training. When contemporary artists use found objects, embrace randomness, or deliberately subvert media expectations, they’re building directly on Dadaist innovations.

From Dada to Surrealism: Evolution Through Division

By 1921-1922, conflict and contradiction erupted among Dada’s members, and the movement splintered into factions—a common fate for revolutionary groups after their initial momentum subsides. French writer André Breton (1896-1966), who had been involved with the Paris Dadaists, emerged as a new leader who believed Dada had exhausted its potential. For Breton, new relevance and direction were essential if the spirit of artistic rebellion was to continue making meaningful interventions in culture.

Unlike many Dadaists who embraced nihilistic destruction as an end in itself, Breton sought to channel the movement’s revolutionary energy toward exploring the unconscious mind. Drawing on Freudian psychoanalysis, he developed a more structured approach to accessing irrational content through techniques like automatic writing and dream analysis. This systematic exploration of the unconscious would soon develop into Surrealism, formalized with Breton’s publication of the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924.

Without a unifying figure to guide the movement forward and with many members gravitating toward Breton’s new ideas, Dada effectively ceased to exist as a cohesive movement by the end of 1922. Yet this apparent failure actually represents a successful transformation. Rather than becoming institutionalized and losing its revolutionary edge, Dada evolved into new forms of artistic rebellion—not only Surrealism but also influencing later developments like Neo-Dada, Fluxus, Pop Art, and Conceptual Art.

This pattern of rupture and renewal ensures that while historical Dada may have ended, its spirit continues to reinvent itself for new generations facing new forms of social crisis. Each revival adapts Dadaist strategies to address contemporary challenges, maintaining the movement’s essential role as art’s perpetual revolutionary conscience.

The Name That Means Everything and Nothing

The origin of the word “Dada” itself embodies the movement’s embrace of chance and rejection of logic. According to the most popular account, the name was discovered when Tristan Tzara and Hugo Ball randomly stabbed a French-German dictionary with a knife, landing on “dada”—French for “hobby horse.” This method of selection perfectly reflected the movement’s commitment to randomness as creative principle.

However, competing origin stories circulate. Richard Huelsenbeck claimed he discovered the word. Others suggest it came from Romanian artists Tzara and Marcel Janco, as “da, da” means “yes, yes” in Romanian. Ball wrote that Zurich nightclub owner Ephraim Kaminka used the term for his wife’s hair lotions. The deliberate ambiguity around the name’s origin was likely intentional—another rejection of definitive history.

The name’s nonsensical quality worked perfectly across languages, allowing the international movement to maintain a consistent identity while avoiding translation issues. Its childish sound—reminiscent of a baby’s first words—also reflected Dada’s interest in primal expression uncorrupted by civilization. As Tzara wrote, “Dada means nothing,” a statement that paradoxically imbued the meaningless syllables with profound significance.

The Geographic Expression of Rebellion

Zurich: The Neutral Birthplace

Dada emerged in Zurich precisely because Switzerland’s neutrality during World War I made it a haven for artistic exiles. At the Cabaret Voltaire, a small nightclub in the Spiegelgasse, Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings gathered artists fleeing conscription and censorship. Their nightly performances featured nonsensical poetry, bizarre costumes, and simultaneous readings in multiple languages—creating chaotic, multilingual expressions that reflected their international composition and anti-nationalist stance.

Berlin: Political Dada

When Dada spread to Berlin after the war, it transformed into a more explicitly political movement. In defeated Germany’s economic collapse and political turmoil, artists like John Heartfield, Hannah Höch, and George Grosz weaponized photomontage to create biting critiques of German society. Their works directly addressed militarism, capitalism, and the hypocrisies of the Weimar Republic, creating a distinctly political version of Dada that used mass media imagery against itself.

New York: Conceptual Provocations

New York Dada developed independently, with Marcel Duchamp arriving in 1915 before the European movement was formally established. The American iteration took a more conceptual, ironic approach, with Duchamp’s readymades challenging fundamental assumptions about artistic creation. Without the immediate trauma of war, New York Dadaists like Man Ray and Francis Picabia focused more on intellectual provocations than direct political protest, creating works that questioned art’s definition rather than society’s failings.

Paris: From Dada to Surrealism

Paris became Dada’s final major center and the site of its transformation. When Tristan Tzara arrived in 1920, he organized provocative events that scandalized Parisian audiences. However, tensions soon developed between Tzara and André Breton, who sought more structure and purpose. This conflict eventually led to Dada’s evolution into Surrealism, as Breton and others redirected the movement’s revolutionary energy toward exploring the unconscious mind through more systematic approaches.

The Dadaist Toolkit: Revolutionary Techniques

Readymades: The Art of Selection

Marcel Duchamp’s readymades—ordinary manufactured objects designated as art through the artist’s selection and minimal modification—represented perhaps Dada’s most radical innovation. By submitting a urinal titled “Fountain” (1917) to an exhibition, Duchamp challenged the very definition of art. Readymades demolished traditional notions of artistic skill, suggesting that conceptual decisions were more important than craftsmanship. This simple gesture established the groundwork for conceptual art, installation art, and countless contemporary practices that prioritize idea over execution.

Photomontage: Cutting Through Reality

Berlin Dadaists pioneered photomontage—cutting and recombining photographs and printed matter to create jarring new compositions. Hannah Höch and John Heartfield developed this technique into a powerful political tool, using mass media imagery against itself. By fragmenting and recombining newspaper photos, advertisements, and text, they created visual disruptions that revealed contradictions in official narratives. This approach anticipated contemporary media criticism and remains a fundamental technique in graphic design, advertising, and digital image manipulation.

Chance Operations: Embracing Randomness

Dadaists elevated chance to a creative principle. Hans Arp created collages by dropping torn paper onto a surface and gluing the pieces where they fell. Tristan Tzara wrote poems by pulling random words from a hat. These methods deliberately removed artistic intention to access what they considered more authentic expression uncorrupted by rational thought. This embrace of randomness as creative method continues to influence contemporary art, music, and literature, particularly in digital algorithms that generate unexpected combinations.

Sound Poetry: Language Beyond Meaning

Hugo Ball performed “sound poems” consisting of invented words and nonsensical syllables, often while wearing bizarre costumes. By reducing language to pure sound divorced from meaning, Dadaists questioned linguistic conventions and explored expression beyond rational communication. This technique broke ground for experimental poetry, performance art, and electronic music that explores the sonic qualities of language independent of semantic content.

The Philosophical Rebellion: Thinking Against Thinking

The Crisis of Reason

Dada emerged as a direct response to the spectacular failure of Western rationality during World War I. If the “rational” systems of nationalism, industrialization, and progress had produced mechanized slaughter on an unprecedented scale, Dadaists reasoned, then reason itself must be questioned. Their embrace of irrationality wasn’t mere absurdity but a deliberate philosophical position: when rational systems produce irrational outcomes, perhaps irrationality offers a more honest approach to reality.

Between Nihilism and Creation

Dada inhabited a productive contradiction between nihilism and creation. While rejecting established meaning systems and embracing chance, Dadaists nevertheless continued to produce art, manifests, and performances. This tension between destructive impulse and creative output generated the movement’s distinctive energy. By clearing away false certainties, Dadaists created space for new possibilities outside conventional frameworks—a rejection that paradoxically enabled new forms of expression.

The Anti-Bourgeois Stance

Class criticism informed Dadaist approaches fundamentally. They attacked bourgeois values not just aesthetically but politically, rejecting the middle-class emphasis on rational progress, material comfort, and moral certainty. Performances deliberately scandalized bourgeois audiences, exposing the hypocrisy of a social class that claimed civilized values while supporting mechanized warfare. This critique of bourgeois culture provided a unifying thread across Dada’s diverse expressions.

Anarchism and Individual Freedom

Dada maintained strong connections to anarchist political thought, particularly in its rejection of hierarchical authority and emphasis on individual freedom. Most Dadaists avoided explicit party politics, instead embracing a more fundamental questioning of authority structures in all forms. Their decentralized, leaderless organization mirrored anarchist principles, as did their techniques that democratized artistic creation. By rejecting artistic skill requirements, they opened creative expression to anyone willing to embrace chance, found materials, and unconventional approaches.

The Art of Proclamation: Dada Manifestos

The Dadaists didn’t just create visual art and performances—they issued manifestos that themselves became artistic acts. These declarations, often as provocative and absurd as their other works, articulated the movement’s anti-principles while paradoxically giving form to its formlessness.

Tristan Tzara’s 1918 “Dada Manifesto” remains the most influential, embodying the movement’s contradictory spirit with declarations like: “DADA DOES NOT MEAN ANYTHING.” The manifesto’s fragmented structure, typographical experimentation, and deliberate contradictions demonstrated Dada’s approach as much as describing it. When Tzara proclaimed “I write a manifesto and I want nothing,” he captured the fundamental Dadaist paradox of creating while rejecting creation.

Richard Huelsenbeck’s “First German Dada Manifesto” (1918) displayed Berlin Dada’s more political edge, explicitly attacking German expressionism as insufficient for addressing postwar realities. His “Collective Dada Manifesto” (1920) further politicized the movement, calling for “revolutionary international union of all creative and intellectual men and women on the basis of radical Communism.”

Hugo Ball’s manifesto, read at the first Dada soirée in 1916, established the movement’s international character: “Dada is a new tendency in art. One can tell this from the fact that until now nobody knew anything about it, and tomorrow everyone in Zurich will be talking about it.” This self-conscious approach to movement-building revealed Dada’s awareness of itself as a constructed phenomenon.

These texts didn’t simply describe existing works but functioned as creative acts that performed the movement’s values. Their continued influence can be seen in artistic manifestos throughout the 20th century and in contemporary forms like internet manifestos, artistic mission statements, and provocative public declarations.

Artistic Relationships: Dada Among Movements

Futurism: Speed, Technology, and Destruction

Dada shared Futurism’s interest in noise, provocation, and disrupting audience expectations. Both movements organized scandalous performances and embraced new technologies. However, Futurism celebrated war, nationalism, and “hygienic” violence—precisely what Dada emerged to oppose. Where Italian Futurists glorified machines and speed, Dadaists viewed technology more skeptically after seeing its destructive potential in World War I.

Expressionism: Emotion vs. Anti-Emotion

German Expressionism’s distorted forms and emotional intensity influenced early Dada, particularly in paintings by artists who moved between movements. However, Dadaists criticized Expressionism’s continued faith in art’s spiritual potential. While Expressionists sought to express profound inner emotions, Dadaists often adopted mechanical, anti-emotional stances or embraced chance operations that deliberately removed personal expression from creation.

Constructivism: Ordered vs. Chaotic Revolution

Both Dada and Constructivism emerged from World War I with revolutionary intentions, but took opposite approaches. Russian Constructivists embraced rational planning, geometric order, and art’s potential utility in building a new society. Dadaists rejected rationality entirely, embracing disorder as their response to societal collapse. Where Constructivists designed practical objects for the revolutionary state, Dadaists created impractical provocations against all states.

From Dada to Surrealism: Evolution or Betrayal?

The relationship between Dada and Surrealism remains complex. André Breton, initially a Paris Dadaist, redirected the movement’s revolutionary energy toward exploring the unconscious mind through more systematic approaches. His First Surrealist Manifesto (1924) established a movement with clearer theoretical foundations based on Freudian psychoanalysis—a level of systematic thinking most Dadaists rejected.

While many Dadaists, including Max Ernst and Man Ray, smoothly transitioned to Surrealism, others viewed the new movement as a betrayal of Dada’s anarchic spirit. Tristan Tzara particularly resisted Surrealism’s more organized approach, seeing it as a domestication of Dada’s wild energy. This tension between structured and unstructured revolutionary approaches continues to characterize avant-garde artistic movements today.

Dada Now: Contemporary Manifestations

Digital Dada: The Internet as Duchamp’s Heir

The internet has become the perfect medium for Dadaist expression. Meme culture operates remarkably like Dada collage—rapidly appropriating, decontextualizing, and recombining existing content to create new meanings. When images circulate online, each iteration adding new elements or placing them in different contexts, they perform the same functions as Hannah Höch’s photomontages but at unprecedented speed and scale.

Glitch art deliberately introduces errors into digital files, embracing technological malfunction as a creative force. This practice connects directly to Dada’s celebration of chance and rejection of control. The aesthetics of failure—pixelation, data corruption, system errors—become visual strategies that challenge our seamless digital world, just as Dadaists embraced the broken and discarded fragments of early 20th century modernity.

NFTs have revived Duchamp’s provocative questions about art’s value and authenticity. When a JPEG sells for millions, it raises the same fundamental questions that “Fountain” posed: What makes something art? Who decides its value? The speculative NFT market, with its wild valuation swings, mirrors the Dadaist embrace of chaos while operating within capitalist structures Dada opposed—a contradiction that itself feels distinctly Dadaist.

Political Art: New Tools for Disruption

Contemporary activist groups employ Dadaist techniques to cut through media fatigue. The Yes Men’s elaborate corporate impersonations, Banksy’s unauthorized public interventions, and Pussy Riot’s guerrilla performances all use absurdity and disruption to expose power structures—continuing Dada’s tradition of using art as political weapon.

During recent protest movements, from Hong Kong to Black Lives Matter, participants have used humor, absurdity, and symbolic disruption alongside traditional protest tactics. These approaches draw from Dada’s playbook: using the unexpected to circumvent censorship, build solidarity, and create compelling media narratives that capture public attention.

Climate activists like Extinction Rebellion stage theatrical die-ins and unexpected interventions in public spaces, creating disruptive spectacles that echo Dada performances at Cabaret Voltaire. By breaking social scripts and creating moments of disorientation, they attempt to shake audiences out of complacency—precisely what Dadaists aimed for in their provocations.

Popular Culture: Mainstream Absorption

Dada’s techniques appear regularly in advertising, fashion, and entertainment. When commercials embrace absurdist juxtapositions, designers create deliberately “ugly” fashion, or music videos employ jarring visual discontinuity, they draw from Dada’s aesthetic toolkit—raising questions about whether revolutionary artistic approaches can retain their power when adopted by commercial entities.

Television shows like “Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!” and “The Eric Andre Show” employ deliberate awkwardness, technical “mistakes,” and absurdist disruption that connect directly to Dadaist performance strategies. These shows create uncomfortable viewing experiences that challenge entertainment conventions while paradoxically functioning as entertainment themselves—a contradiction that captures Dada’s complex legacy.

Create Your Own Dada: A Participatory Guide

Five-Minute Dadaist Poetry

Try Tristan Tzara’s recipe for creating a Dadaist poem:

- Take a newspaper article or any text

- Cut it into individual words

- Place the words in a bag

- Shake the bag vigorously

- Remove words one by one

- Copy them in the exact order they emerge

The resulting poem will contain unexpected combinations that bypass conscious control. For a digital version, try cutting and pasting sentences from different online articles and randomly rearranging them using a random number generator.

Everyday Readymades Challenge

Transform ordinary objects into art following Marcel Duchamp:

- Select a manufactured object from your environment

- Change its context (place it where it doesn’t belong)

- Rename it something unrelated to its function

- Document your creation with a photograph

- Write a brief, provocative title and explanation

Remember: the selection itself is the creative act. Your readymade doesn’t need to be beautiful or skillfully made—it should provoke questions about what constitutes art.

Chance Collage

Create a Hans Arp-inspired composition:

- Gather paper in different colors or patterns

- Tear (don’t cut) the paper into various shapes

- Drop the pieces onto a surface from standing height

- Glue them exactly where they land

- Accept the random arrangement as your composition

This exercise helps release creative control and embrace chance—a fundamental Dadaist principle that can free you from conventional aesthetic judgments.

Spot the Dada Influence

Develop your Dada-detection skills by identifying these principles in everyday life:

- Randomness and chance operations in creative works

- Deliberate disruption of expectations

- Repurposing of existing materials in unexpected ways

- Absurdist juxtapositions that create new meanings

- Questioning of artistic conventions and authority

Once you start looking, you’ll find Dadaist elements everywhere—from internet culture to advertising, political protest to fashion trends. This awareness connects you to a revolutionary artistic spirit that continues to shape how we see, think, and create more than a century after Dada’s birth.

Dadaism The Story

What is the origin of Dadaism?

Dadaism emerged in 1916 during World War I as a reaction to the horrors of war, nationalism, and societal structures. It was founded by a group of artists and intellectuals in Zurich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire, including Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, and Jean Arp. They rejected conventional art and logic, embracing randomness, absurdity, and anti-art aesthetics. Dadaists sought to challenge authority, expose the meaningless violence of war, and disrupt traditional artistic norms through spontaneous and irrational creations.

How did Dadaism challenge traditional art?

Dadaism rejected the idea that art had to be beautiful, logical, or meaningful. Instead, it embraced chaos, irrationality, and provocation. Artists like Marcel Duchamp introduced the concept of the “readymade,” where ordinary objects became art simply by being selected. Techniques such as photomontage, collage, and performance art disrupted traditional artistic standards. Dadaists sought to destroy established rules, ridiculing museums, institutions, and the idea that art should serve societal or commercial purposes. Their goal was to shock audiences and break free from artistic conventions.

Who were the key figures in Dadaism?

Several influential artists and writers defined the Dada movement. Hugo Ball, a co-founder, pioneered Dada poetry and performance art. Tristan Tzara wrote Dadaist manifestos, shaping the movement’s ideology. Marcel Duchamp revolutionized art with his readymades, including the famous Fountain (a signed urinal). Hans Arp experimented with abstract collage and chance-based creations. Francis Picabia and Man Ray used Dadaist principles in painting and photography. These figures pushed artistic boundaries, leaving a lasting impact on modern and contemporary art movements.

How did Dadaism influence later artistic movements?

Dadaism laid the foundation for many avant-garde and experimental movements, including Surrealism, Conceptual Art, and Performance Art. Surrealism, led by André Breton, borrowed Dada’s rejection of logic but focused on dreams and the subconscious. Conceptual artists adopted Dada’s emphasis on ideas over aesthetics, leading to minimalism and installation art. Punk culture, protest art, and digital meme culture also reflect Dada’s rebellious and absurdist spirit. The movement’s influence can still be seen in contemporary art, fashion, advertising, and political satire.

Why did Dadaism decline, and is it still relevant today?

Dadaism began to decline in the early 1920s as some members, like Breton, shifted toward Surrealism, and others moved on to different creative endeavors. However, its impact remains alive in modern artistic and cultural expressions. The rise of digital media, political activism, and meme culture echoes Dada’s disruptive techniques. Absurd humor, nonsensical poetry, and provocative installations all carry the essence of Dadaism. Its spirit of rebellion against conformity and traditional structures ensures that Dada’s legacy continues to shape creativity and cultural discourse today.