The Revolutionary Minds Behind Art’s Most Rebellious Movement

The Birth of an Anti-Art Revolution

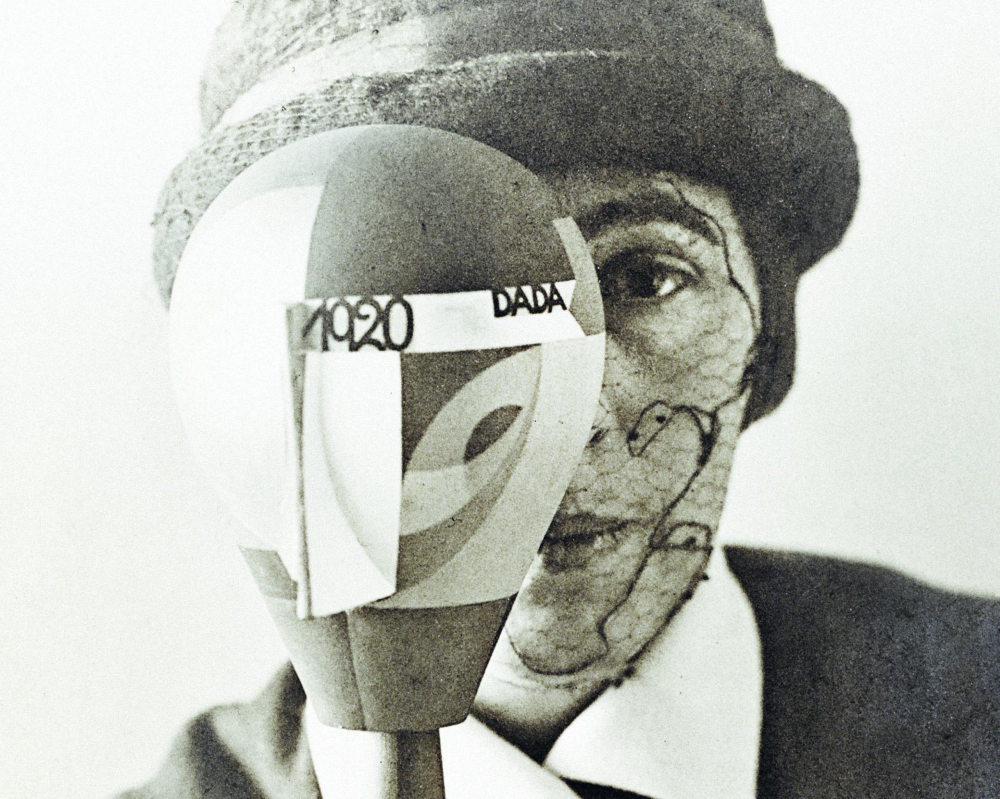

Every artistic revolution begins with visionaries who challenge established conventions, but Dada stands apart in how thoroughly its founders rejected the very notion of artistic tradition. Unlike movements that evolved gradually, Dada erupted as a deliberate anti-art provocation in 1916 amidst the chaos of World War I. The historical founders of Dada art weren’t merely introducing new aesthetic styles—they were questioning whether art should exist in its conventional form at all.

A Global Coalition of Radical Thinkers

The original Dada artists represented a remarkably diverse international coalition. Poets, painters, sculptors, writers, and performers gathered first at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire, creating a crucible of radical thinking that would spread to Berlin, Paris, New York, and beyond. What united these disparate personalities wasn’t a shared visual style but a revolutionary attitude that challenged every artistic assumption of their time.

From Unity to Divergence

As with many avant-garde movements, Dada eventually experienced internal divisions as it grew beyond its initial explosive moment. What began as a unified protest against war and bourgeois values gradually splintered into various interpretations and approaches, with some members maintaining Dada’s nihilistic edge while others sought new directions that would eventually lead to Surrealism and other movements.

Expanding Art’s Definition

The key figures of early Dada transcended traditional artistic boundaries in ways that still feel radical today. These weren’t simply painters or sculptors but cultural provocateurs who expanded art’s definition to include found objects, chance operations, nonsensical performances, and provocative manifestos. Their most profound contribution was perhaps their shared conviction that art wasn’t separate from life but could be found in everyday gestures, objects, and experiences—that “a work of art could be considered as life itself.”

The Essential Voices

The founders highlighted below represent the movement’s essential voices—from the Cabaret Voltaire’s originators to the international figures who transformed Dada from local protest to global phenomenon. Through their radical approaches, these old Dada artists permanently altered the landscape of modern art, establishing principles of conceptual and performance-based creation that continue to reverberate through contemporary culture.

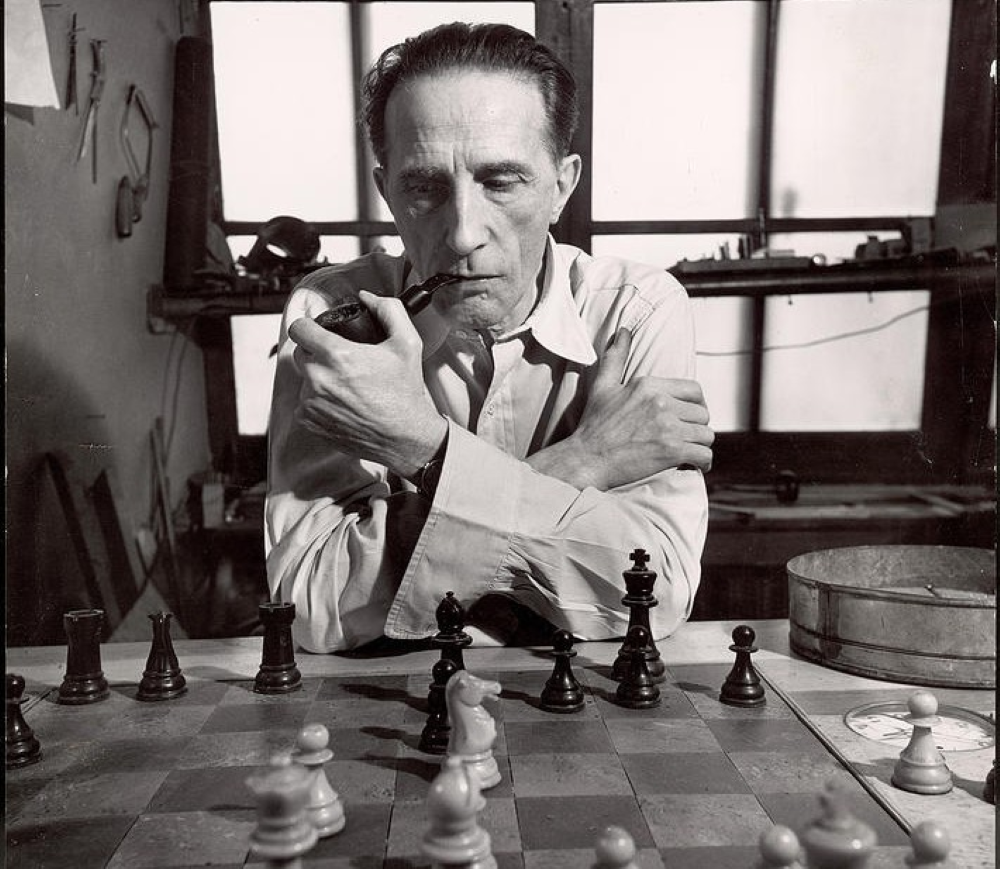

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp is credited with changing the future of art in a way that very few artists can claim to have influenced. Having survived the lessons of Cubism, Futurism, and Constructivism, which can be seen within his early paintings, he spectacularly led the American Dada movement. With the philosophies of previous avant-garde movements combined with a rejection of mass production, colonialism, and materialism Duchamp challenged the notion of what is art through the creation of readymades. These ‘readymades’ were his alternative to representing objects in paint and was his idea of presenting various objects as art themselves.

These selections were often mass produced items which were available to all consumers by which he designated them as art and gave them a title. This notion sent shock waves through the art world which can still be felt today as he both distorted and disrupted centuries of ideological discursive thinking about art and the artist’s role as a maker of unique handmade objects. Despite his refusal to be defined and labelled as adhering to any one particular artistic movement.

Much of Duchamp’s work can be seen as aligning itself with surrealists through the exploration of the mechanism of sexuality and desire. For this reason, as well as the notion that art should be driven first and foremost by ideas, Duchamp is often considered as the father of conceptual art as he steadfastly refused to follow any conventional artistic movement and refused to be put into a box by critics or his peers.

Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927)

This German baron’s widow became found her Dadaist nature in New York. Whilst she made a few artistic works herself in the form of paintings and poetry she also was featured in Duchamp and Man Ray’s film.The Baroness Shaves Her Pubic Hair. She was obsessed with Duchamp and it is rumoured that she was a fundamental figure in Duchamp’s famous urinal piece – which has transcended through the ages becoming more recently appropriated by Yoko Ono.

Duchamp is rumoured to have stolen the credit for this artwork from Elsa as he stated in a letter to his sister that a ‘female friend’ of his ‘sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture’. Many art historians and academics are of the strong opinion that the urinal bears a strong resemblance to the work of Elsa.

Hannah Hoch (1889-1978)

Hannah was a leading figure within the Dada movement in Berlin. She specialized in collages and splicing images together from popular magazines, journals and fashion magazines in an artistic style heavily influenced by Cubism. Akin with all figures within the Dada movement, Hannah was primarily interested in providing a commentary on society of the time; which because of the war, the feminist movement, and drastic changes to production, was undergoing enormous social changes.

Hannah quickly became a social critic and a lesbian who typified the ideals behind the liberated ‘new women’ of the Weimar Republic.

Man Ray (1890-1976)

In 1915, Man Ray met French craftsman Marcel Duchamp, and together they teamed up on numerous creations and shaped the New York gathering of Dada specialists. However, Man Ray was convinced that ‘all New York is Dada’ and because of that there simply was not enough room for a rival. As such in 1921, Ray moved to Paris and got to be connected with the Parisian Dada and Surrealist circles of specialists and authors.

He specialized in the medium of photography but was also a master of multiple mediums and was often considered a spark plug of the American Dada movement. Once he moved to Paris though, he remained steadfastly connected to his true passion of photography. He eventually redefined the style of photography and focused on ‘rayographs’ the idea of producing abstract photography without the use of a camera.

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948)

Kurt Schwitters was a standout amongst the most captivating rebels of the art of the twentieth century. His craft is perpetually aligned with Dada, albeit individual conflicts kept him from being accepted formally into the movement. An ideal shared by a lot of those considered to be Dadaists. As with Duchamp, Schwitters nature meant that he would never be completely dedicated to any singular movement, even one of dissent. His absence of enthusiasm for governmental issues separated him from the fundamentals of German Dada’s, as did his abode in Hanover as opposed to Berlin like the majority of German Dadaists.

By 1918, at 31 years old, he had found that he was not on a basic level a painter, but rather that for him the embodiment of workmanship lay in the blend of existing materials. In 1919 he named his own type of composition “Merz,” to flag that his photos were unmistakable from Cubism, Expressionism, or even Dada, and after some time he extended the name to every one of his exercises, including verse and performance.

Sophie Taeuber (1889-1943)

Her myriad of expression styles included painting, dance, woven artwork, drawing, embroidery, furniture and interior design, photography, structural planning, set outline and puppet making. She was one of the only Swiss members of Dad and curiosity being exemplified within her expression and artwork is her trademark. In Zurich, Sophie took an interest in the Dadaist exercises, dicing for Dada soirees at the Cabaret Voltaire from 1916 forward. She later began choreographing Dadaist works and making ensembles and sets.

Founders Of Dada Art

Who were the main founders of Dada Art?

The Dada movement was founded in 1916 at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, Switzerland. Key figures included Hugo Ball, a poet and performer who introduced Dadaist sound poetry; Tristan Tzara, a writer who became the movement’s main theorist; Marcel Duchamp, who pioneered the concept of readymades; Hans Arp, known for his abstract collages; and Francis Picabia, who embraced mechanical and absurd imagery. These artists rejected traditional art, favoring randomness, absurdity, and anti-war expression.

What inspired the founders of Dada Art to create the movement?

The founders of Dada Art were deeply affected by the horrors of World War I. They saw the war as a failure of rational thinking and society’s traditional values. Their response was to create an art movement that embraced irrationality, absurdity, and anti-establishment ideals. Dadaists used nonsense poetry, experimental performance, and unconventional materials to challenge conventional art and social structures. They believed that rejecting logic and embracing chaos was the only way to respond to a world that had become senseless and violent.

What role did Hugo Ball play in the Dada movement?

Hugo Ball was one of the earliest and most influential founders of Dada Art. In 1916, he established the Cabaret Voltaire, a space where artists could experiment with poetry, music, and performance art. He introduced sound poetry, which used meaningless syllables to break away from structured language. His famous performance in a cubist costume made of cardboard became an iconic moment in Dada history. Ball’s ideas laid the foundation for Dada’s rejection of logic and artistic conventions.

How did Tristan Tzara shape the Dada movement?

Tristan Tzara was a writer, poet, and one of the most vocal leaders of Dadaism. He wrote Dadaist manifestos, which outlined the movement’s anarchic and anti-art philosophy. His poetry, created using the cut-up technique, was random and nonsensical, rejecting traditional literary rules. Tzara helped spread Dadaism to other countries, including France, where he later influenced Surrealism. His rebellious spirit and outspoken nature made him one of the key figures in defining the movement’s chaotic and provocative essence.

How did Marcel Duchamp contribute to Dada Art?

Marcel Duchamp redefined the concept of art with his readymades, ordinary objects transformed into artworks by simple selection and placement. His most famous piece, Fountain (1917), was a porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt,” challenging traditional ideas of artistic craftsmanship and originality. Duchamp’s work questioned the purpose of art and laid the groundwork for conceptual art. His influence extended beyond Dadaism, shaping modern art movements like Surrealism, Pop Art, and Minimalism. His radical ideas remain essential to contemporary art discourse.

| Name | Country | Date of Birth | Date of Death | Art Mediums |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hugo Ball | Germany | 1886-02-22 | 1927-09-14 | Poetry, Performance Art |

| Tristan Tzara | Romania | 1896-04-16 | 1963-12-25 | Poetry, Performance Art, Writing |

| Marcel Duchamp | France | 1887-07-28 | 1968-10-02 | Painting, Sculpture, Conceptual Art |

| Jean (Hans) Arp | Germany/France | 1886-09-16 | 1966-06-07 | Sculpture, Painting, Poetry |

| Sophie Taeuber-Arp | Switzerland | 1889-01-19 | 1943-01-13 | Painting, Textile Design, Dance |

| Raoul Hausmann | Austria | 1886-07-12 | 1971-02-01 | Collage, Photography, Performance Art |

| Hannah Höch | Germany | 1889-11-01 | 1978-05-31 | Collage, Photomontage, Painting |

| Kurt Schwitters | Germany | 1887-06-20 | 1948-01-08 | Collage, Sound Poetry, Installation Art |

| Francis Picabia | France | 1879-01-22 | 1953-11-30 | Painting, Writing, Typography |

| Man Ray | USA/France | 1890-08-27 | 1976-11-18 | Photography, Painting, Film |

| Max Ernst | Germany | 1891-04-02 | 1976-04-01 | Painting, Sculpture, Collage |

| George Grosz | Germany | 1893-07-26 | 1959-07-06 | Painting, Drawing, Caricature Illustration |

| Richard Huelsenbeck | Germany | 1892-04-23 | 1974-04-30 | Poetry, Writing, Performance Art |

| Emmy Hennings | Germany | 1885-02-17 | 1948-08-10 | Performance Art, Poetry |

| Marcel Janco | Romania/Israel | 1895-05-24 | 1984-04-21 | Painting, Architecture, Mask Design |

| Hans Richter | Germany | 1888-04-06 | 1976-02-01 | Painting, Filmmaking, Graphic Art |

| Theo van Doesburg | Netherlands | 1883-08-30 | 1931-03-07 | Painting, Writing, Architecture |

| John Heartfield | Germany | 1891-06-19 | 1968-04-26 | Photomontage, Graphic Design |

| Johannes Baader | Germany | 1875-06-22 | 1955-01-15 | Architecture, Writing, Performance Art |

| Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven | Germany/USA | 1874-07-12 | 1927-12-15 | Performance Art, Poetry, Sculpture |

| Arthur Segal | Romania | 1875-07-23 | 1944-06-23 | Painting, Woodcuts |

| Walter Serner | Austria | 1889-01-15 | 1942 | Writing, Poetry |

| Philippe Soupault | France | 1897-08-02 | 1990-03-12 | Poetry, Writing |

| Beatrice Wood | USA | 1893-03-03 | 1998-03-12 | Ceramics, Painting, Writing |

| Christian Schad | Germany | 1894-08-21 | 1982-02-25 | Painting, Photomontage |

| Suzanne Duchamp | France | 1889-10-20 | 1963-09-11 | Painting |

| Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes | France | 1884-06-19 | 1974-07-09 | Writing, Painting, Music |

| Clément Pansaers | Belgium | 1885-05-01 | 1922-10-31 | Poetry, Writing |

| Julius Evola | Italy | 1898-05-19 | 1974-06-11 | Painting, Philosophy, Writing |

| Paul Éluard | France | 1895-12-14 | 1952-11-18 | Poetry |

| André Breton | France | 1896-02-19 | 1966-09-28 | Writing, Poetry |

| Louis Aragon | France | 1897-10-03 | 1982-12-24 | Poetry, Writing |

| Jean Crotti | France | 1878-04-24 | 1958-01-30 | Painting |

| Jean Cocteau | France | 1889-07-05 | 1963-10-11 | Writing, Filmmaking, Painting |

| Guillaume Apollinaire | Italy/France | 1880-08-26 | 1918-11-09 | Poetry, Writing |

| Viking Eggeling | Sweden | 1880-10-21 | 1925-05-19 | Painting, Filmmaking |

| Lyonel Feininger | USA/Germany | 1871-07-17 | 1956-01-13 | Painting, Caricature Illustration |

| Otto Dix | Germany | 1891-12-02 | 1969-07-25 | Painting, Printmaking |

| John Covert | USA | 1882-12-27 | 1960-01-10 | Painting |