The Revolutionary Spirits Behind Dadaism

Challenging Art’s Very Definition

Learn About Dadaists – they weren’t simply creating new styles—they were fundamentally challenging what art could be. Emerging during World War I, these revolutionary artists rejected traditional aesthetics, bourgeois values, and the rationality they believed had plunged Europe into unprecedented destruction.

Embracing the Absurd

What distinguished Dadaists was their deliberate embrace of the absurd and irrational. Unlike previous avant-garde movements seeking new forms of beauty, Dadaists celebrated nonsense, chance operations, and provocations designed to shock audiences out of complacency.

Shaped by War and Exile

Most Dadaists were exiles or refugees who had fled conscription or persecution, gathering in neutral zones like Zurich. Their work directly responded to the mechanized slaughter that had destroyed optimistic beliefs in progress and civilization.

Cross-Disciplinary Innovators

This diverse group came from backgrounds in fine arts, poetry, theater, and design. What united them wasn’t a shared visual style but a common attitude of irreverent questioning and experimental approach that crossed traditional boundaries between artistic media.

Three Defining Characteristics

Dadaist artists maintained an international outlook during a time of intense nationalism, embraced interdisciplinary approaches that ignored traditional boundaries, and cultivated provocative relationships with audiences, transforming art from passive contemplation to active engagement.

The Birth of Dada: Founding Figures

The Cabaret Voltaire: Dada’s Birthplace

Hugo Ball (1886-1927) and Emmy Hennings (1885-1948) established the Cabaret Voltaire in February 1916, creating both an artistic venue and intellectual sanctuary in neutral Zurich. Their small nightclub at Spiegelgasse 1 provided the essential space where Dadaism could develop amid the chaos of war.

Tristan Tzara: The Movement’s Voice

Romanian-born Tristan Tzara (1896-1963) quickly became Dadaism’s chief theorist and international ambassador. His charismatic performances featured nonsensical poetry, while his publishing efforts—particularly the influential journal Dada—transformed a local phenomenon into an international movement.

Jean Arp: Master of Chance

Jean (Hans) Arp (1886-1966), an Alsatian artist who had moved to Zurich to avoid military service, pioneered techniques central to Dadaist practice. His use of chance operations in creating collages and his biomorphic sculptures provided a distinctive visual language that connected Dadaism with abstract art.

The Name That Changed Art History

The movement’s name embodied its spirit of chance and absurdity. The most accepted account is that Ball and Tzara discovered the word “dada” (a French child’s term for hobbyhorse) while randomly inserting a knife into a dictionary—a nonsensical term that perfectly captured their rejection of rational meaning.

From Cabaret to Movement

By summer 1916, the original group had been joined by Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, and Sophie Taeuber. Though the Cabaret Voltaire closed after only five months, the ideas incubated there spread throughout Europe and across the Atlantic, permanently transforming artistic practice and public understanding of art itself.

The Zurich Circle: Dada’s Original Provocateurs

Creative Refugees in Neutral Territory

The original Zurich Dadaists formed a remarkable concentration of artistic talent, brought together by circumstance and a shared revulsion toward the war. Using Switzerland’s neutrality as their shield, these international artists created a movement that transcended national boundaries during an era of extreme nationalism.

Richard Huelsenbeck: The Rhythmic Revolutionary

Richard Huelsenbeck (1892-1974) brought percussive energy to early Dada performances, often beating drums while reciting poetry. After his time in Zurich, he transported Dadaist ideas to Berlin, where he published the influential First German Dada Manifesto in 1918 and helped establish the movement’s more politically radical German branch.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Bringing Craft to the Avant-Garde

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943) challenged the hierarchy between fine and applied arts through her innovative work across media. Trained in textile design, she created geometric abstractions in embroidery, beadwork, and painting that influenced the development of Constructivism. Her performances at the Cabaret Voltaire in costumes of her own design embodied the movement’s interdisciplinary spirit.

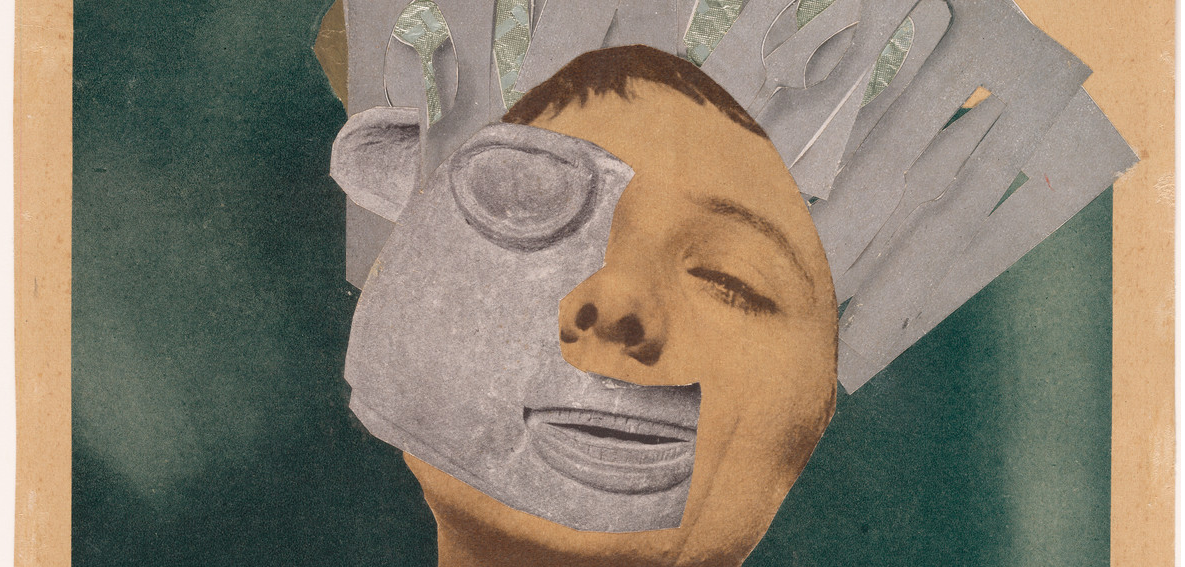

Marcel Janco: Masks and Modernism

Romanian-born Marcel Janco (1895-1984) created masks for Dada performances that transformed poetry recitals into ritualistic events. His expressionist paintings of Cabaret Voltaire performances document the raw energy of these gatherings, while his architectural training later informed his contributions to avant-garde building design.

Collaborative Performances: Dada’s Living Art

The Zurich Dadaists pioneered a collaborative approach to performance that dissolved boundaries between creator and spectator. Their “simultaneous poems” featured multiple voices reciting in different languages simultaneously, creating a sonic collage that mirrored the fragmentation of modern experience and defied rational interpretation.

The Gallery Space: Expanding Beyond Cabaret

After Cabaret Voltaire closed, the group established Galerie Dada in March 1917, which hosted exhibitions, soirées, and lectures that expanded Dadaist ideas beyond performance into the visual arts. Here, the movement developed a more coherent identity while maintaining its commitment to artistic freedom and experimentation.

Berlin Dadaists: Political Radicalism

Revolutionary Context: Art Amid Upheaval

When Dadaism reached Berlin in 1917-1918, it encountered a city in political turmoil. The German empire was collapsing, revolution was brewing, and artists were taking sides. Berlin Dadaists embraced a more overtly political stance than their Zurich counterparts, using their art as a weapon against both traditional aesthetics and the failing political order.

Raoul Hausmann: The Dadasoph

Raoul Hausmann (1886-1971), self-proclaimed “Dadasoph,” pioneered photomontage as a Dadaist technique, cutting and reassembling media images to create jarring juxtapositions that exposed societal contradictions. His iconic Mechanical Head (The Spirit of Our Age) (1919)—a wooden mannequin head adorned with measuring tools and mechanical parts—perfectly captured the movement’s critique of modern rationality.

Hannah Höch: Pioneer of Photomontage

Hannah Höch (1889-1978) created some of Berlin Dada’s most enduring works through her innovative photomontages. Her masterpiece Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919-1920) combined images from mass media to critique politics, gender roles, and technology. As the only woman in the Berlin Dada Club, she added critical feminist perspectives to the movement.

George Grosz and John Heartfield: Art as Political Weapon

George Grosz (1893-1959) and John Heartfield (born Helmut Herzfeld, 1891-1968) developed some of Dada’s most overtly political art. Grosz’s caustic drawings savaged the German military and bourgeoisie, while Heartfield revolutionized photomontage as anti-fascist propaganda. Their collaborative projects, including The Art Scab (1920), attacked conventional art while promoting revolutionary politics.

Johannes Baader: The Oberdada

Johannes Baader (1875-1955), a trained architect who styled himself “Oberdada,” specialized in public interventions and provocations. His infamous disruption of a service at Berlin Cathedral and his “proclamations” published in newspapers brought Dadaist chaos into public spaces, challenging institutional authority and conventional behavior.

The Dada Fair: Showcasing Political Art

The First International Dada Fair in 1920, organized by Grosz, Heartfield, and Hausmann, presented nearly 200 works of Dadaist art. The exhibition’s centerpiece—Grosz and Heartfield’s assemblage The Middle-Class Philistine Heartfield Gone Wild with a pig’s head suspended from the ceiling—resulted in their prosecution for “defaming the German military,” demonstrating the genuine political stakes of Berlin Dada’s provocations.

Paris Dada: From Provocation to Surrealism

The Parisian Evolution

In Paris, Dadaism arrived in January 1920 when Tristan Tzara moved from Zurich, bringing the movement’s provocative energy to a city already steeped in avant-garde traditions. Parisian Dada emerged within an established artistic community, creating a unique dynamic that would eventually transform into Surrealism.

Marcel Duchamp: The Ready-Made Revolutionary

Though his involvement with organized Dadaism was tangential, Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) embodied its spirit through his revolutionary “ready-mades.” His Fountain (1917)—a urinal signed “R. Mutt”—and L.H.O.O.Q. (1919)—a postcard of the Mona Lisa with added mustache—challenged fundamental assumptions about artistic creation and value, influencing generations of conceptual artists.

Man Ray: Photography Reimagined

American-born Man Ray (1890-1976) brought photography into the Dadaist realm through his innovative techniques and surreal imagery. His “rayographs“—created by placing objects directly on photosensitive paper—eliminated the camera entirely, while works like Gift (1921)—an iron with metal tacks attached to its surface—transformed everyday objects into menacing artifacts.

Francis Picabia: The Mercurial Provocateur

Francis Picabia (1879-1953) embodied Dadaism’s restless spirit through his constant stylistic shifts. His mechanomorphic drawings satirized modern society’s obsession with technology, while his intentionally crude “machinic portraits” mocked artistic conventions. As editor of the journals 391 and Cannibale, he published provocative texts and images that extended Dadaism’s reach.

André Breton: From Dada to Surrealism

André Breton (1896-1966) initially embraced Dadaism’s nihilistic energy but soon sought more constructive approaches to exploring the unconscious mind. His Magnetic Fields (1920), co-authored with Philippe Soupault, pioneered “automatic writing”—a technique that would become central to Surrealism. By 1924, Breton’s publication of the First Surrealist Manifesto marked Dadaism’s transformation into a new movement.

The Theatrical Provocations

Parisian Dadaists staged notorious events that scandalized traditional audiences. The Festival Dada at Salle Gaveau in May 1920 featured readings of nonsensical manifestos to an increasingly hostile crowd, exemplifying the movement’s antagonistic relationship with its public. These provocations employed theatrical techniques while rejecting conventional theater’s illusions and emotional manipulations.

New York Dada: American Innovations

Transatlantic Connections

New York Dadaism developed somewhat independently from its European counterpart, emerging around 1915 among artists connected to Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery “291” and the Arensberg salon. Though the term “Dada” wasn’t applied until later, these artists were already exploring similar ideas about artistic conventions and absurdist humor.

The Arensberg Circle: Dada’s American Patrons

Walter and Louise Arensberg created a crucial gathering place for avant-garde artists in their New York apartment. Their collection of modern art and their weekly salons brought together figures like Duchamp, Man Ray, and others who shared Dadaist sensibilities. This supportive environment allowed for collaborative experiments that defined American Dada’s character.

Beatrice Wood: The Mama of Dada

Beatrice Wood (1893-1998), who styled herself the “Mama of Dada,” moved between the worlds of visual art, writing, and performance. Her ironic drawings and satirical texts appeared in The Blind Man, a short-lived but influential journal she co-edited with Duchamp and Henri-Pierre Roché. Her later ceramic work extended Dadaist principles into applied arts with ingenious glazing techniques.

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven: The Dada Baroness

The eccentric Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927) embodied Dadaism through her very existence, transforming herself into a living artwork through provocative costumes assembled from found objects. Her poetry used fragmented language and sexual imagery that defied conventions, while her found-object sculptures (including God, possibly in collaboration with Morton Schamberg) anticipated later conceptual approaches.

Publications as Artistic Platforms

New York Dadaists created influential journals that documented their ideas and provocations. The Blind Man and Rongwrong, though short-lived, provided platforms for experimental writing and reproductions of controversial artworks. New York Dada, published by Man Ray and Duchamp in 1921, attempted to formalize the connection between European Dadaism and American experiments.

Machine Aesthetic and American Culture

New York Dadaists embraced America’s industrial development and mechanical aesthetic more enthusiastically than their European counterparts. Man Ray’s Self-Portrait (1916) with a handprint and bell-push, and Morton Livingston Schamberg’s precise paintings of mechanical forms reflected this fascination with modern technology, distinguishing American Dadaism through its ambivalent celebration of the machine age.

Cologne and Hanover: Regional Centers

Cologne Dada: Brief but Influential

The Cologne Dada group, active from 1919-1920, developed a distinctive approach that, while less overtly political than Berlin Dada, maintained an equally subversive attitude toward artistic and social conventions. Despite its brief existence, this regional center produced works and ideas that significantly influenced later artistic developments.

Max Ernst: Collage Innovations

Max Ernst (1891-1976) emerged as Cologne Dada’s central figure, pioneering collage techniques that would later become fundamental to Surrealism. His Fatagaga series (created with Johannes Theodor Baargeld) combined found photographs with drawn elements, creating disturbing hybrid images that challenged viewers’ sense of reality and transformed visual narrative possibilities.

Johannes Theodor Baargeld: The Radical Publisher

Johannes Theodor Baargeld (pseudonym of Alfred Gruenwald, 1892-1927) brought political radicalism and publishing experience to Cologne Dada. Before embracing art, he edited the leftist newspaper Der Ventilator, which reached 20,000 readers before being banned by occupation authorities. His collages and photomontages incorporated mathematical elements, reflecting his training as an economist.

The Infamous Exhibition

In April 1920, Ernst and Baargeld organized the legendary Dada-Vorfrühling (Dada-Early Spring) exhibition in the courtyard of a Cologne brewery. Visitors entered through a public toilet and encountered deliberately shocking works including a young girl in a communion dress reciting obscene poetry and an axe placed beside an artwork inviting viewers to destroy it. Police closed the exhibition for “obscenity,” generating precisely the controversy the Dadaists sought.

Hanover Dada: Kurt Schwitters’ One-Man Movement

While Berlin, Paris, and Zurich Dadaists formed collaborative groups, Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) essentially constituted a one-man Dada movement in Hanover. Rejected by the Berlin Dadaists for his perceived bourgeois tendencies, Schwitters developed his own artistic approach he called “Merz”—a nonsensical term derived from a fragment of the word “Kommerz” (commerce).

The Merz Revolution

Schwitters’ Merz works transformed urban detritus—tram tickets, broken furniture, wire mesh, newspaper clippings—into complex assemblages that elevated discarded materials to the status of fine art. His collages featured meticulous formal arrangement that distinguished them from the more deliberately chaotic works of other Dadaists, creating a bridge between Dadaist techniques and Constructivist aesthetics.

The Merzbau: Environmental Art

Schwitters’ most ambitious project, the Merzbau (Merz Building), transformed his Hanover home into an ever-growing sculptural environment. Beginning in 1923, this architectural collage incorporated found objects, personal mementos, and abstract sculptural elements that grew organically across rooms. Though destroyed during World War II bombings, this pioneering work anticipated later developments in installation and environmental art.

Sound Poetry and Performance

Beyond visual art, Schwitters made significant contributions to sound poetry through works like Ursonate (Primordial Sonata, 1922-1932), a 35-minute composition of nonlexical vocalizations arranged in sonata form. His public performances of this work throughout Europe demonstrated Dadaism’s exploration of language beyond semantic meaning, influencing later sound poets and experimental musicians.

Artistic Techniques of the Dadaists

Photomontage: Cutting Reality to Reveal Truth

Photomontage—the technique of cutting and reassembling photographic images—emerged as one of Dadaism’s most significant innovations. Berlin Dadaists including Hannah Höch, Raoul Hausmann, and John Heartfield pioneered this approach, using mass media images to create jarring juxtapositions that critiqued politics, gender roles, and consumer culture.

Collage Beyond Cubism

While Cubists had introduced collage into fine art, Dadaists expanded its possibilities through more radical juxtapositions and conceptual approaches. Kurt Schwitters’ Merz collages integrated actual urban detritus, while Max Ernst’s surreal combinations of Victorian engravings created dreamlike narratives that disrupted rational interpretation.

The Ready-made Revolution

Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades—ordinary objects elevated to the status of art through the artist’s selection and contextual displacement—represented perhaps Dadaism’s most profound conceptual breakthrough. From the iconic Fountain (1917) to the Bicycle Wheel (1913), these works shifted artistic value from craftsmanship to concept, challenging fundamental assumptions about creativity and aesthetics.

Chance Operations and Automatism

Dadaists embraced randomness as a creative method, deliberately surrendering control to chance operations. Jean Arp created collages by dropping torn paper onto surfaces and gluing pieces where they fell. Tristan Tzara’s instructions for making poetry by randomly drawing cut-up newspaper words from a hat exemplified this approach, which later influenced Surrealist automatism.

Sound Poetry and Performance

Dadaists liberated poetry from semantic meaning through sound poetry experiments. Hugo Ball’s performances at Cabaret Voltaire featured nonsensical phonetic poems recited while wearing bizarre costumes. Kurt Schwitters’ Ursonate (1922-1932) developed this approach into an extended composition, while “simultaneous poems” featured multiple voices reciting in different languages simultaneously.

Typography and Print Experiments

Dadaist publications revolutionized graphic design through experimental typography that reflected their disruptive content. Raoul Hausmann’s “poster poems” arranged letters in nonlinear patterns, varying fonts and sizes to create visual-verbal compositions. Johannes Baader and George Grosz incorporated random typographical elements in their publications, creating visual chaos that challenged conventional reading.

Assemblage and Object Transformation

Dadaists transformed everyday objects through unexpected combinations and contextual shifts. Man Ray’s Gift (1921)—an iron with metal tacks attached to its surface—rendered a domestic tool menacing and useless. Francis Picabia’s mechanical assemblages combined disparate objects into pseudo-machines that parodied modern society’s technological obsessions.

Provocative Performance and Public Intervention

Dada performances deliberately provoked audience reactions through absurdist theatrical techniques. Events at Cabaret Voltaire and later venues featured simultaneous actions, nonsensical recitations, and provocative gestures designed to generate confusion or outrage. Johannes Baader’s disruption of a service at Berlin Cathedral and other public interventions extended these provocations beyond artistic venues into everyday spaces.

Women Dadaists: Beyond the Male Narrative

Rewriting Art History

Traditional accounts of Dadaism, like many avant-garde movements, often marginalized women artists’ contributions. Contemporary scholarship has worked to correct this imbalance, revealing how women Dadaists were not peripheral figures but essential innovators whose work challenged both artistic conventions and gender roles in early 20th-century society.

Hannah Höch: Pioneering Critical Perspectives

While included in the Berlin Dada section, Hannah Höch’s contributions merit deeper examination. As the only woman officially admitted to the Berlin Dada Club, she faced significant sexism from her male colleagues. Despite this, her photomontages like Cut with the Kitchen Knife addressed gender politics more explicitly than most Dadaists, incorporating images of “New Women” alongside political figures and machinery to critique patriarchal power structures.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: The Multi-Disciplinary Innovator

Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s work spanned textiles, painting, sculpture, architecture, and performance, systematically erasing boundaries between “fine art” and “craft”—categories often used to demote women’s creative work. Her geometric abstractions in the Dada-Köpfe (Dada Heads) series transformed traditional wooden millinery forms into modernist sculptures, while her marionettes for König Hirsch (King Stag) brought abstraction to puppet theater.

Emmy Hennings: The Forgotten Founder

Emmy Hennings (1885-1948) co-founded Cabaret Voltaire with Hugo Ball yet is often reduced to a footnote in Dadaist history. An accomplished poet, performer, and puppet-maker, she managed the cabaret and performed nightly, her haunting singing and dramatic recitations establishing the venue’s distinctive atmosphere. Her published works, including Das Brandmal (The Stigma, 1920) and Gefängnis (Prison, 1919), drew on her experiences of poverty and incarceration to create powerful feminist literature.

Baroness Elsa: Dada Embodied

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927) transformed her very existence into a Dadaist artwork, creating provocative costumes from found objects and parading through New York streets as a living collage. Her experimental poetry explored sexuality and gender with unprecedented frankness, while recent scholarship suggests she may have contributed to or even created iconic works attributed to male artists, including the possibility of her involvement with Duchamp’s Fountain.

Suzanne Duchamp: Beyond Her Brother’s Shadow

Suzanne Duchamp (1889-1963), often overshadowed by her famous brother Marcel, created significant Dadaist works that combined mechanical elements with painting. Her piece Un et une menacés (A and One Threatened) (1916) incorporated collage, text, and mechanical drawing to explore gender relationships and technological anxiety, demonstrating her distinctive artistic voice within the Dadaist idiom.

Céline Arnauld: Dada’s Literary Voice

Romanian-born poet Céline Arnauld (1885-1952) edited the Dadaist journal Projecteur and published experimental poetry collections including Poèmes à claires-voies (Poems with Open Views, 1920). Though largely forgotten until recent scholarly recovery, her work appeared in major Dada publications, and she participated actively in Parisian Dada performances, contributing a significant literary voice to the movement.

Mina Loy: Transnational Dadaist

Mina Loy (1882-1966) moved between Futurist, Dadaist, and Surrealist circles, creating poetry, prose, and visual art that challenged conventions of gender and artistic expression. Her manifesto “Feminist Manifesto” (1914) and poems like “Songs to Joannes” combined radical form with explicit content about female sexuality and gender politics, embodying Dadaist disruption of social and literary norms.

The Dadaist Legacy: Influence on Later Movements

From Protest to Paradigm Shift

Though active for less than a decade, Dadaism’s radical rethinking of art’s purpose and methods catalyzed a paradigm shift that continues to shape contemporary artistic practice. What began as protest against specific historical circumstances evolved into a fundamental questioning of art’s definition and boundaries, creating possibilities that subsequent movements would explore in diverse directions.

Surrealism: The Unconscious Awakened

Surrealism emerged directly from Dadaism, with many key figures—including André Breton, Max Ernst, and Man Ray—participating in both movements. Surrealists transformed Dadaist chance operations into techniques for accessing the unconscious mind, while retaining Dadaism’s commitment to disrupting conventional perception. The First Surrealist Manifesto (1924) codified this evolution from Dada’s primarily destructive approach to Surrealism’s constructive exploration of the marvelous.

Neo-Dada: Postwar Revival

In the 1950s and early 1960s, artists including Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns revived Dadaist strategies in what critics termed Neo-Dada. Rauschenberg’s “Combines” incorporated found objects into painting, while Johns’ flag paintings questioned representation in ways reminiscent of Duchamp. In Japan, the Gutai group similarly embraced chance, materiality, and action in ways that echoed Dadaist approaches.

Fluxus: Intermedial Experimentation

The international Fluxus network, active from the early 1960s, explicitly acknowledged Dadaist influence while developing its own approach to art, performance, and publication. Artists like George Maciunas and Yoko Ono created event scores and intermedia works that, like Dadaism, challenged distinctions between art forms and between art and everyday life. Fluxus’ democratic approach to materials and distribution extended Dadaism’s critique of artistic preciousness.

Pop Art: Mass Media Appropriation

While aesthetically different from Dadaism, Pop Art extended Dadaist techniques of appropriation and collage into engagement with post-war consumer culture. Andy Warhol’s screen-printed celebrity portraits and consumer products built on Dadaist ready-mades, while Richard Hamilton’s collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (1956) employed Höch-like photomontage techniques to comment on modern life.

Conceptual Art: The Primacy of Ideas

Conceptual art’s prioritization of idea over execution derives directly from Duchamp’s ready-mades. When Joseph Kosuth presented One and Three Chairs (1965)—consisting of a physical chair, a photograph of the chair, and a dictionary definition—he extended Duchamp’s questioning of representation and artistic value. Sol LeWitt’s statement that “the idea becomes a machine that makes the art” encapsulates this Dadaist legacy.

Performance Art: The Living Artwork

Contemporary performance art traces its lineage to Dadaist provocations at Cabaret Voltaire and subsequent venues. Artists like Carolee Schneemann, Joseph Beuys, and Marina Abramović developed approaches to embodied art that extend Dadaist explorations of presence, provocation, and the artist’s body as medium. The emphasis on ephemeral, unrepeatable events challenges art market commodification in ways that echo Dadaist concerns.

Digital Art and Internet Culture

Even digital art and internet culture show Dadaist influence. Net.art pioneers like Jodi.org created websites that disrupt conventional user experience, while meme culture employs collage, juxtaposition, and absurdist humor in ways that parallel Dadaist techniques. Glitch art deliberately introduces errors into digital systems, embracing chance and dysfunction as creative principles in the Dadaist tradition.

Collecting and Exhibiting Dadaist Works

Institutional Recognition: From Rejection to Reverence

Dadaism’s journey from radical rejection by artistic institutions to celebration within those same institutions represents one of art history’s great ironies. The movement that sought to destroy traditional museums and art markets is now extensively documented, collected, and exhibited by major museums worldwide—testament to Dadaism’s enduring significance despite its anti-institutional origins.

Major Museum Collections: Where to See Dada Today

Several museums hold particularly significant Dadaist collections. The Museum of Modern Art in New York houses extensive Dadaist holdings, including key works by Duchamp, Man Ray, and Schwitters. The Centre Pompidou in Paris maintains one of the world’s largest Dada archives, while Kunsthaus Zürich preserves important documents from the movement’s origins.

Specialized Collections: Dedicated Archives

Beyond major museums, specialized institutions preserve Dadaist legacy. The International Dada Archive at the University of Iowa houses extensive documentation and digital resources. The Kurt Schwitters Archive at Sprengel Museum Hannover maintains the largest collection of Schwitters’ work, while the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich has been restored as a museum and cultural center at Dadaism’s birthplace.

Market Value: Collecting Dada

Dadaist works command extraordinary prices in today’s art market, despite (or perhaps because of) their creators’ anti-commercial stance. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades are among the most valuable artworks of the 20th century, with editions of Fountain valued in the millions. Collages by Hannah Höch and Kurt Schwitters likewise command premium prices when they rarely appear at auction.

The Rarity Factor: Ephemeral Art

Many Dadaist creations were deliberately ephemeral or subsequently destroyed, making surviving works particularly valuable. Nazi persecution led to the destruction of numerous works labeled “degenerate art,” while others were lost through war damage, including Schwitters’ original Merzbau. This scarcity, combined with growing scholarly and public interest, has dramatically increased the value of surviving Dadaist artifacts.

Major Exhibitions: Dada Retrospectives

Several landmark exhibitions have shaped understanding of Dadaism. The Museum of Modern Art’s “Dada, Surrealism, and Their Heritage” (1968) established the movement’s art historical importance, while the Centre Pompidou, National Gallery of Art, and MoMA’s “Dada” (2005-2006) exhibition represented the most comprehensive survey ever mounted, traveling between Paris, Washington, and New York.

Digital Collections: Democratizing Access

Digital technology has democratized access to Dadaist works previously limited to specialists. The International Dada Archive Digital Collection offers scans of rare publications, while the Smithsonian’s Dada Research Portal provides scholarly resources. These digital initiatives align with Dadaism’s democratic impulse to make art accessible beyond elite institutions.

Contextual Exhibitions: Understanding Dada

Contemporary curators increasingly contextualize Dadaism within broader cultural currents. Exhibitions like Tate Modern’s “Dada and Surrealism Reviewed” examined the movements’ publishing activities, while the Berlinische Galerie’s “Hannah Höch: Picture Book” explored connections between avant-garde art and children’s perception. These approaches reveal Dadaism’s intersections with politics, technology, and everyday life.

Collecting Strategies: Building a Dada Collection

For today’s collectors interested in Dadaism, several approaches exist despite high prices for original works. Dada publications, which were produced in larger numbers than unique artworks, represent more accessible entry points. Modern editions of Dada portfolios, authorized reproductions, and contemporary works by artists working in Dadaist traditions offer alternatives for collectors passionate about the movement but unable to acquire museum-quality originals.

About Dadaists

Who were the key figures in the Dadaist movement?

Dadaism featured a diverse group of artists, writers, and performers who rejected traditional artistic values. Key figures included Tristan Tzara, a poet and key theorist behind Dada; Hugo Ball, known for his sound poetry and performances at Cabaret Voltaire; Marcel Duchamp, who revolutionized art with his ready-mades; Hannah Höch, a pioneer of photomontage; and Francis Picabia, who experimented with abstraction and satire. Others like Jean Arp, Raoul Hausmann, and Man Ray also played vital roles in shaping the movement.

What were the main beliefs and goals of Dadaists?

Dadaists sought to disrupt established norms in art, literature, and culture by embracing randomness, absurdity, and anti-establishment ideas. They opposed the rationalism that had led to World War I and rejected the idea that art should have meaning or serve aesthetic ideals. Instead, they favored spontaneity, chance, and provocation, using techniques like collage, photomontage, and performance art to challenge artistic conventions. Their ultimate goal was to dismantle traditional artistic hierarchies and redefine creativity as an act of rebellion.

How did Dadaists create their art?

Dadaists employed radical techniques to break away from conventional artistic forms. They used collage, cutting and pasting random images to form new compositions; photomontage, layering photographs to create surreal visuals; ready-mades, everyday objects presented as art (popularized by Duchamp); and sound poetry, which deconstructed language into nonsensical sounds. Performance art was also central, with spontaneous, chaotic performances at Cabaret Voltaire that blended poetry, music, and movement. These experimental approaches emphasized unpredictability and rejected traditional artistic craftsmanship.

What was the relationship between Dadaism and other art movements?

Dadaism interacted with various artistic movements, sometimes in opposition and sometimes as an influence. It rejected Expressionism for its emotional intensity, mocked Futurism for its pro-war stance, and shared political engagement with Constructivism, though with different approaches. The most significant impact was on Surrealism, which evolved from Dada’s rejection of reason but added a structured exploration of the subconscious mind. Later, Neo-Dada and Pop Art revived Dadaist techniques, influencing artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol.

Why did the Dadaist movement decline, and what is its legacy?

Dadaism faded in the early 1920s as its members either moved into other movements, like Surrealism, or found their anarchic approach unsustainable in the long term. However, its influence persists in contemporary art, particularly in Conceptual Art, Performance Art, and Multimedia Art. The Dadaist spirit of challenging authority and questioning artistic value continues to inspire artists, from Fluxus performers to digital artists experimenting with AI and generative art. Its radical rejection of artistic norms remains a foundational influence in modern creative expression.