The Origins and Spirit of Neo-Dadaism

From Historical Art Movement to Internet Culture

What Is Neo-Dadaism – In today’s digital landscape, absurdist internet humor has become a ubiquitous part of online culture. Many art historians and cultural critics have noted striking parallels between this contemporary phenomenon and Neo-Dadaism, an influential artistic movement that emerged in the 1960s. This connection has sparked discussions about a potential resurgence of Neo-Dadaist principles in our digital era. But what exactly connects the experimental art of the mid-20th century with the internet memes that populate our screens today?

The Controversial Pioneers

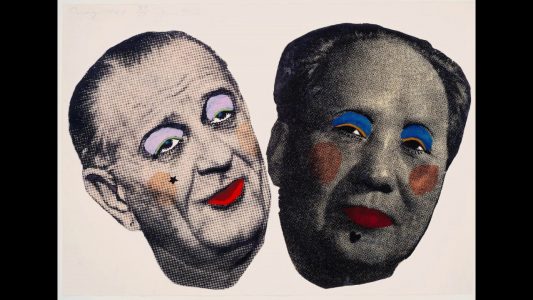

Neo-Dadaism found its voice through pioneering artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, whose work often provoked controversy and challenged artistic conventions. These artists boldly incorporated elements of popular culture into their creations, wielding irony as a powerful tool to question established norms. Their approach wasn’t entirely new—it drew inspiration from Dadaism, one of the revolutionary avant-garde movements that transformed art in the early 20th century.

Art as Rebellion Against a Senseless World

The original Dadaist movement emerged as a profound response to societal upheaval. Much like other artistic movements throughout history, Dadaism developed as a reaction to the world its artists inhabited—a world that had become incomprehensible amid the chaos of World War I and the relentless march of capitalism. The Dadaists essentially posed a provocative question: If the world itself has abandoned reason and meaning, why should art remain confined to traditional notions of sense and order? Their objective was not merely to create aesthetically pleasing works but to elicit powerful emotional and intellectual responses from viewers, challenging the very foundations of what constituted “art.”

This spirit of rebellion and questioning continues to resonate in both Neo-Dadaism and contemporary digital culture, suggesting that when societal structures appear increasingly absurd, art often responds in kind.

Neo-Dadaism’s Parallels to Modern Internet Culture

Rebellion Against Capitalist Aesthetics and Existential Absurdity

That profound connection between historical Neo-Dadaism and today’s absurdist internet humor becomes clearer when examining their shared philosophical underpinnings. Both movements fundamentally reject the aesthetics of capitalism, though they express this rejection through different mediums and contexts. While the original Dadaists and Neo-Dadaists confronted the physical world’s contradictions, contemporary internet humor grapples with the digital realm—a space that can often feel more overwhelming and alienating than physical reality itself.

These artistic expressions also confront the perceived pointlessness of existence. Young generations have embraced memes as a powerful coping mechanism for navigating modern society and its daily absurdities. Through dark humor, they articulate their frustrations and profound dissatisfaction with reality. This creative outlet serves a dual purpose: it helps them process their disillusionment while providing momentary relief and comfort. Even when faced with feelings of hopelessness about changing the world around them, memes offer a way to laugh in the face of absurdity—a distinctly Neo-Dadaist response to societal confusion.

The Social Language of Digital Neo-Dadaism

Absurdist internet humor functions as both critique and parody of online society. This form of expression is densely packed with references, creating a rich tapestry of meaning that can be impenetrable to those who aren’t immersed in internet culture. Young people particularly value memes that reference other memes, as recognizing these connections signifies membership in a shared cultural community. This creates a sense of belonging that mirrors how Neo-Dadaist artists formed their own counter-cultural identity in the 1960s.

Memes as Evolving Art Forms

Perhaps the most fascinating characteristic of internet memes—and what connects them so deeply to Neo-Dadaist principles—is their capacity for constant regeneration. Like the Neo-Dadaist “combines” and “assemblages” that repurposed existing materials into new contexts, a single meme can spawn countless derivative works, sometimes referred to as sub-memes. This evolutionary nature reflects the Neo-Dadaist emphasis on transformation, recontextualization, and the continuous questioning of established forms. The digital canvas, like the Neo-Dadaist studio, becomes a space where nothing remains static and meaning is perpetually in flux.

Neo-Dadaism in Contemporary Digital Expression

Repurposing Popular Culture Icons

Content creators in today’s digital landscape have developed techniques that mirror Neo-Dadaist approaches to art-making. A common practice involves appropriating characters from popular television shows or cartoons—figures that maintain widespread recognition even among those who haven’t engaged with the original content. Cartoon characters prove particularly effective material because they already possess inherent absurdity in their design and behavior. When extracted from their original context and paired with unrelated text, these familiar figures transform into something even more bizarre and thought-provoking. This process of decontextualization and recontextualization represents the very essence of absurdist internet humor and directly parallels how Neo-Dadaists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns incorporated familiar imagery into unexpected contexts.

The Evolution of Abstract Meme Formats

The Galaxy Brain Meme stands as a perfect example of abstract meme formats that embody Neo-Dadaist principles. This widely recognized template visually compares an established cultural scale with increasingly radical concepts as the depicted brain expands. What makes this format particularly Neo-Dadaist is its deliberate lack of rigid structure—it provides an empty canvas where creators can insert virtually any content, including references to other memes. The only governing principle is that as the galaxy brain expands, the corresponding concepts should become progressively more abstract or absurd. Many cultural critics observe that this meme brilliantly encapsulates contemporary society’s tendency toward irrationality and abstraction, much as Neo-Dadaist works reflected the societal contradictions of their era.

The Death of the Author in Digital Culture

Perhaps one of the most fascinating parallels between Neo-Dadaism and internet meme culture lies in their shared approach to authorship. In the digital realm, we typically remember and share memes themselves while forgetting the accounts or individuals who created them (unless we already follow that creator). This anonymous quality of meme creation strongly echoes the Dadaist and Neo-Dadaist rejection of traditional authorship, where the artistic creation takes precedence over the identity of its creator. Both movements challenge the capitalist notion of art as individual intellectual property, instead embracing a more communal understanding of creative expression that values the work’s cultural impact above its commercial or personal attribution. This rejection of artistic ego aligns perfectly with Neo-Dadaism’s critique of art market conventions and traditional notions of artistic genius.

The Digital Divide: Neo-Dadaist Expression in the Internet Age

Anonymity and Artistic Liberation in Online Spaces

The digital environment creates a unique psychological distance between creator and audience that has significant parallels to the Neo-Dadaist approach to art-making. This separation emboldens authors to venture into darker, more provocative humor than they might express in face-to-face interactions. The internet becomes a confessional space where creators can push boundaries they would carefully avoid in more intimate settings like family gatherings. This liberation from social constraints echoes how Neo-Dadaist artists used their work to challenge societal taboos and conventions, often creating deliberately provocative pieces that would have been unacceptable in traditional artistic circles.

Moreover, part of the appeal for digital creators lies in the knowledge that their work creates a division—between those who understand the references and those who remain outside the cultural conversation. This deliberate obscurity parallels how Neo-Dadaist artists often created works with layers of meaning accessible only to those familiar with their artistic language and philosophy.

Generational Understanding and Critical Engagement

The generational gap in meme comprehension reflects how young people have grown up immersed in this absurdist language, developing fluency in its evolving forms and references. However, this familiarity sometimes comes without the critical framework needed to analyze these cultural products. Just as Neo-Dadaist works required viewers to develop new ways of seeing and interpreting art, internet absurdism demands new forms of media literacy that many young consumers have yet to develop fully—potentially creating vulnerability to manipulation through these powerful communication channels.

The Medium Shapes the Message

Internet humor is profoundly influenced by its distribution platforms, particularly the rapid-scrolling environment of social media sites like Twitter. The unprecedented accessibility of content has transformed how we engage with artistic expression. As we scroll through endless feeds, only the most striking or provocative content manages to interrupt our attention—creating a survival-of-the-fittest dynamic for digital content that favors extremes. Posts are deliberately crafted to generate emotional reactions, whether discomfort, anger, or bitter laughter, much as Neo-Dadaist artists aimed to provoke strong responses rather than mere aesthetic appreciation.

Neo-Dadaism vs. Internet Absurdism: Evolution or Revolution?

Shared DNA but Distinct Identities

While the parallels between internet absurdist humor and historical Neo-Dadaism are significant, it would be an oversimplification to classify internet humor as merely a digital extension of Dadaism. The connections are undeniable—both movements employ irony, reject traditional aesthetics and logical structures, and aim to generate powerful emotional reactions. However, internet humor represents an evolutionary step rather than a direct continuation.

Memes as Cultural Artifacts of the Digital Age

It might initially seem strange to classify memes as a genuine artistic movement, but throughout history, each era has developed distinctive forms of creative expression that reflected its unique circumstances. When both Dadaism and Neo-Dadaism first emerged, they were dismissed by traditionalists who struggled to recognize them as legitimate artistic movements. Dada art, with its seemingly nonsensical approach, initially baffled audiences before eventually being recognized as a profound reflection of its historical moment.

Similarly, today’s memes serve as authentic cultural artifacts that perfectly capture the fragmented, ironic, and often nihilistic sensibility of early 21st-century society. Future historians and sociologists will likely study these digital creations to understand our current cultural landscape, much as we now study Neo-Dadaist works to comprehend the social transformations of the 1960s. It’s entirely plausible that future generations will analyze memes in history classes as primary sources that illuminate the complex psychological and social dynamics of our time, offering insights into how we processed everything from political upheaval to technological anxiety through the lens of absurdist humor.

Historical Context and Timeline of Neo-Dadaism

Post-War Emergence and Cultural Response

Neo-Dadaism emerged in the 1950s and early 1960s as a direct response to the cultural climate of post-World War II society. While the original Dadaist movement arose from the devastation of World War I, Neo-Dadaism developed during the Cold War era when consumer culture was rapidly expanding and the world was grappling with nuclear anxiety. Artists felt a similar sense of disillusionment with established systems as their Dadaist predecessors, but their context was distinctly different—characterized by unprecedented economic prosperity alongside existential dread.

The movement gained momentum as a reaction against the dominance of Abstract Expressionism in the art world. Where Abstract Expressionism celebrated the emotional intensity of the individual artist, Neo-Dadaism questioned the very notion of artistic genius and embraced collaborative, chance-based approaches to creation. This timing was crucial—Neo-Dadaism bridged the gap between the raw emotional expression of the immediate post-war period and the cool detachment that would later characterize Pop Art and Minimalism.

From Dada to Neo-Dada: Evolution of Ideas

Neo-Dadaism wasn’t merely a revival of earlier Dadaist principles—it was a sophisticated evolution that adapted Dadaist techniques to address contemporary concerns. The movement became officially recognized around 1958 when critic Robert Rosenblum used the term to describe the work of artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. However, many of the artists themselves rejected this classification, highlighting the movement’s inherent resistance to definitive categorization—a resistance that was itself quintessentially Dadaist.

The movement’s development wasn’t limited to America. In Japan, the Neo-Dada Organizers formed in 1960, creating provocative works that challenged Japan’s rapid industrialization and the cultural changes resulting from American occupation. This international dimension demonstrated how Neo-Dadaist principles resonated across different cultural contexts where societies were experiencing rapid transformation and questioning traditional values.

Key Neo-Dadaist Techniques and Media

The Revolutionary “Combines” and Found Objects

At the heart of Neo-Dadaism lay the revolutionary technique of incorporating everyday objects into artwork—a direct inheritance from Marcel Duchamp’s earlier “readymades.” Robert Rauschenberg pioneered what he called “combines,” works that existed in the space between painting and sculpture, incorporating items like bed quilts, stuffed animals, and street signs alongside traditional painting techniques. His famous work “Monogram” (1955-1959), featuring a taxidermied goat with a tire around its middle standing on a painted canvas, epitomized this approach.

These techniques deliberately challenged the precious nature of art objects and blurred the boundary between art and life. By elevating discarded items to the status of art, Neo-Dadaists questioned value systems that separated the aesthetic from the everyday. This radical approach transformed what materials could be considered valid for artistic expression and paved the way for later developments in installation art.

Performance, Chance, and Destruction as Artistic Process

Neo-Dadaism expanded beyond static objects to embrace performance and process-based art. Artists like Jean Tinguely created self-destructing kinetic sculptures, most famously his “Homage to New York” (1960), which was designed to destroy itself in the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art. This embrace of impermanence and chance directly challenged the art market’s emphasis on collectible, permanent objects.

Similarly, performance became central to many Neo-Dadaist expressions. Allan Kaprow’s “Happenings” invited audience participation and emphasized the unpredictable nature of art events. John Cage’s musical compositions incorporated silence and random sounds, allowing chance operations to determine musical structure. These approaches reflected the Neo-Dadaist belief in relinquishing artistic control and embracing the chaotic nature of existence—a philosophical position that would later find echoes in the randomness and collective creation of internet meme culture.

Geographical Centers of Neo-Dadaism

The New York School: American Neo-Dada’s Epicenter

New York City emerged as the primary hub of American Neo-Dadaism in the 1950s, creating a vibrant community of artists who regularly exchanged ideas and collaborated on projects. The city provided fertile ground for artistic experimentation during this period, with its dynamic gallery scene and growing status as the world’s art capital after World War II. Artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, John Cage, and Allan Kaprow formed an interconnected network that challenged conventional artistic practices through their innovative approaches.

The influence of artist Marcel Duchamp, who had relocated to New York decades earlier, proved crucial to this development. Duchamp’s earlier Dadaist ideas gained renewed attention as younger artists discovered his work and even formed personal relationships with him. The Black Mountain College in North Carolina also played a significant role, hosting experimental workshops where many Neo-Dadaist principles were developed and refined before being fully realized in New York’s artistic landscape.

Japanese Neo-Dada Organizers: A Parallel Movement

While American Neo-Dadaism has received more historical attention, equally significant developments were occurring in Japan. The Neo-Dada Organizers, formed in Tokyo in 1960, included artists like Ushio Shinohara, Genpei Akasegawa, and Shusaku Arakawa. These artists responded to Japan’s rapid post-war industrialization and the cultural upheaval caused by American occupation with provocative works that challenged traditional Japanese aesthetics and social norms.

The Japanese movement was particularly notable for its confrontational performance art and use of discarded materials that reflected the waste of consumer society. Shinohara became known for his “boxing paintings,” created by punching canvases with paint-soaked boxing gloves, while Akasegawa’s controversial work with counterfeit money led to his prosecution by the Japanese government. Though developing somewhat independently from American Neo-Dada, these parallel movements shared a similar philosophical approach to questioning authority, challenging artistic traditions, and incorporating chance and everyday materials into their creative processes.

Influential Works and Examples

Iconic Neo-Dadaist Creations That Defined the Movement

Several landmark works have come to exemplify Neo-Dadaism’s revolutionary approach to art-making. Jasper Johns’ “Flag” (1954-55) transformed the American flag—a potent national symbol—into an ambiguous art object through his encaustic painting technique. By presenting a familiar icon in a new context, Johns forced viewers to question their relationship to everyday symbols and the boundary between representation and reality.

Robert Rauschenberg’s “Bed” (1955) similarly challenged artistic conventions by mounting his own quilt, sheet, and pillow on a wooden support, then applying paint, toothpaste, and nail polish to create a work that existed between painting and sculpture. This piece not only questioned the materials appropriate for art but also blurred the line between the intimate personal space of a bed and the public display of an artwork.

Conceptual Breakthroughs and Provocations

Jean Tinguely’s self-destructing sculpture “Homage to New York” (1960) represented Neo-Dadaism’s embrace of impermanence and spectacle. Designed to self-destruct in the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art, the work consisted of a complex machine made from bicycle wheels, motors, a piano, and various junk materials that operated for 27 minutes before catching fire and being extinguished by firefighters. This deliberate embrace of destruction as artistic process directly challenged the art market’s emphasis on permanence and collectability.

John Cage’s composition “4’33″” (1952), though often associated with experimental music, embodied Neo-Dadaist principles by consisting of four minutes and thirty-three seconds of performed silence. By framing ambient sounds as music, Cage redefined what constituted art and invited audiences to experience everyday noise as aesthetic material. These watershed works collectively redefined artistic practice and laid the groundwork for contemporary conceptual art, highlighting how Neo-Dadaism’s influence extends far beyond its immediate historical context.

Connection to Other Art Movements

Neo-Dadaism as a Crucial Bridge in Art History

Neo-Dadaism’s position in the timeline of 20th-century art movements is particularly significant as it served as a pivotal bridge between Abstract Expressionism and the emergence of Pop Art. Where Abstract Expressionism emphasized the emotional gesture and the artist’s individual psyche, Neo-Dadaism reintroduced everyday objects and cultural references that would later become central to Pop Art’s celebration of consumer culture. This transitional role makes Neo-Dadaism essential for understanding the development of contemporary art.

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, while embracing Neo-Dadaist techniques, also laid crucial groundwork for Pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. The use of commercial imagery and found objects in Neo-Dadaist works directly influenced Pop Art’s appropriation of mass media and advertising. However, where Neo-Dadaism maintained a critical stance toward consumer culture, Pop Art often embraced these elements with ambiguous irony rather than outright rejection.

International Offshoots and Parallel Developments

Neo-Dadaism’s influence extended beyond America to inspire multiple international movements. In France, Nouveau Réalisme (New Realism) emerged under the leadership of critic Pierre Restany, with artists like Yves Klein and Arman creating works that shared Neo-Dadaist principles while developing distinct approaches to found objects and consumer waste. Klein’s famous monochrome blue paintings and “anthropometries” (where he used nude models as “living brushes”) exemplified this connection.

The Fluxus movement, founded by George Maciunas in 1961, took Neo-Dadaist principles even further into the realm of interdisciplinary performance and participatory art. Fluxus artists like Joseph Beuys and Yoko Ono created events and installations that emphasized process over product and invited audience participation in ways that directly built upon Neo-Dadaist experimentation. These international developments demonstrate how Neo-Dadaist principles spread globally, adapting to different cultural contexts while maintaining core philosophical approaches to challenging artistic conventions.

Critical Reception and Legacy

From Derision to Recognition: The Evolution of Response

When Neo-Dadaist works first appeared in galleries and museums in the 1950s, many critics responded with confusion and dismissal—much as critics had rejected the original Dadaist works decades earlier. Mainstream art critics often characterized these new works as jokes or provocations without serious artistic merit. The New York Times famously described Rauschenberg’s work as “collision between abstract expressionism and children’s art,” while other critics questioned whether incorporating found objects could truly be considered skilled artistic practice.

However, by the mid-1960s, critical reception began to shift dramatically. Influential critics like Leo Steinberg developed new theoretical frameworks like the “flatbed picture plane” to understand and contextualize these revolutionary approaches. Museums began acquiring Neo-Dadaist works for their permanent collections, and by the 1970s, many of these once-controversial pieces had become canonical examples of post-war American art. This evolution from rejection to celebration mirrors the trajectory of many avant-garde movements and demonstrates how radically Neo-Dadaism transformed artistic standards.

Enduring Influence on Contemporary Art Practice

The legacy of Neo-Dadaism extends far beyond its immediate historical moment. Contemporary installation art, conceptual art, and performance art all build directly upon foundations established by Neo-Dadaist experimentation. The movement’s emphasis on process over product, its questioning of authorship, and its democratization of materials have become fundamental aspects of contemporary artistic practice across disciplines.

Artists like Ai Weiwei, Damien Hirst, and Maurizio Cattelan continue to employ Neo-Dadaist strategies of provocation and recontextualization in their work. The YBA (Young British Artists) movement of the 1990s, with works like Tracey Emin’s “My Bed” (1998), directly referenced Neo-Dadaist precedents like Rauschenberg’s “Bed.” This ongoing influence demonstrates how Neo-Dadaism wasn’t merely a historical movement but rather a fundamental shift in artistic thinking that continues to inform how artists approach their practice in the 21st century.

What Is Neo-Dadaism

What is Neo-Dadaism?

Neo-Dadaism is an art movement that emerged in the 1950s, blending elements of Dadaism with contemporary influences. It challenged traditional artistic conventions by incorporating everyday objects, mass media imagery, and performance elements. Artists used humor, irony, and absurdity to critique consumer culture and artistic norms.

How does Neo-Dadaism differ from traditional Dadaism?

While both movements reject artistic conventions, Dadaism was a response to World War I, using anti-art aesthetics to oppose societal structures. Neo-Dadaism, on the other hand, emerged post-World War II, reflecting consumer culture and mass media influences. It borrowed Dada’s experimental spirit but incorporated modern materials and techniques, such as collage, assemblage, and performance art.

Who are the key artists associated with Neo-Dadaism?

Important figures include Robert Rauschenberg, known for his “Combines” that fused painting and sculpture, and Jasper Johns, famous for reinterpreting familiar symbols like flags and numbers. Other artists, such as John Cage in music and Merce Cunningham in dance, contributed by experimenting with randomness and audience participation.

What are the main themes and techniques of Neo-Dada art?

Neo-Dada artists embraced mixed media, found objects, and unconventional materials, rejecting traditional boundaries between artistic disciplines. Themes included consumerism, mass production, and media saturation. Techniques like collage, assemblage, and chance-based creation were used to challenge artistic traditions and blur the line between art and everyday life.

How did Neo-Dadaism influence later art movements?

Neo-Dadaism paved the way for Pop Art, Conceptual Art, and Fluxus by inspiring artists to incorporate popular culture, everyday materials, and performative elements into their work. The movement’s rejection of artistic hierarchy and embrace of experimentation influenced contemporary artists who continue to challenge art’s role in society.

Comments

One response to “What Is Neo-Dadaism – Daring And Taboo Rebel Art”

[…] is an interesting distinction. While memes exist to provoke and supply a quick reaction, relatively speaking—and many are very clever in their absurdism to do exactly this—Neo-Dada thrives on flooding […]