The Arrival of the Avant-Garde: Dadaism’s Journey to Australia

While Dadaism erupted in the cultural centers of Europe in response to the horrors of World War I, its revolutionary ideas would eventually travel across oceans to influence Dadaism In Australia art and culture. This artistic movement, with its deliberate irrationality, anti-aesthetic stance, and rejection of prevailing standards, found fertile ground in Australia’s evolving cultural landscape during the interwar period, though its manifestation would take on uniquely Australian characteristics.

The transmission of Dadaist ideas to Australia occurred against the backdrop of a nation still forming its cultural identity. As a relatively young nation that had only federated in 1901, Australia was simultaneously developing its own artistic voice while looking to European movements for inspiration and validation. The geographic isolation that had long shaped Australian cultural development paradoxically created both barriers to and hunger for international artistic innovations.

Australian artists and intellectuals first encountered Dadaism primarily through imported publications, correspondence with European counterparts, and the return of Australians who had experienced the European avant-garde firsthand. These cultural exchanges, though limited by distance and the communication technologies of the era, provided crucial pathways for Dadaist techniques and philosophies to enter Australian artistic consciousness.

The European Context and Australian Reception

Dadaism emerged in 1916 at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire, when a group of artists including Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Tristan Tzara, and others began staging provocative performances that rejected rationality and aesthetic standards. The movement quickly spread to Berlin, Paris, New York, and other centers, with each location developing distinctive approaches to the Dadaist ethos of artistic rebellion.

Australia’s reception of these radical ideas was inevitably delayed and filtered through multiple cultural lenses. The conservative artistic establishment that dominated Australian cultural institutions in the early 20th century initially viewed Dadaism with skepticism and sometimes outright hostility. Traditional landscape painting and nationalist themes remained predominant in mainstream Australian art circles well into the 1930s.

Nevertheless, a small but significant network of forward-thinking artists, writers, and patrons became increasingly receptive to international modernism, including Dadaism’s provocative stance. These cultural pioneers recognized that Dadaism’s questioning of authority and convention might offer valuable tools for developing a more sophisticated and internationally engaged Australian artistic identity.

Pioneers and Provocateurs: Key Figures in Australian Dadaism

Unlike the concentrated eruption of Dadaism in Europe, Australia’s engagement with Dada principles emerged through the work of individuals and small groups operating at the margins of the mainstream art world. These Australian artists adapted Dadaist techniques and philosophies to local contexts, often blending them with other modernist approaches.

J.W. Power: Australia’s Connection to European Dada

J.W. Power (1881-1943) stands as one of the most significant links between European Dadaism and Australian art. Born in Sydney, Power studied medicine before moving to Europe, where he became immersed in modernist circles. Though primarily associated with Cubism and geometric abstraction, Power’s work and connections provided an important channel for Dadaist ideas to reach Australian shores.

Power’s cosmopolitan perspective and substantial financial resources enabled him to build an impressive collection of modern art and establish relationships with key European figures. His bequest to the University of Sydney would later provide Australian artists and students with unprecedented access to materials documenting the European avant-garde, including Dadaism.

Adrian Lawlor and the Melbourne Underground

In Melbourne, artist and writer Adrian Lawlor (1889-1969) incorporated elements of Dadaist absurdity and provocation into his multidisciplinary practice. Lawlor’s irreverent approach to art-making, his interest in chance and the unconscious, and his deliberate challenging of bourgeois taste reflect Dadaist influences adapted to the Australian context.

Lawlor’s home became an informal salon for artists interested in modernist experimentation, creating a space where Dadaist techniques could be discussed and explored away from the conservatism of official art institutions. His writings in avant-garde publications helped disseminate ideas associated with Dadaism to a wider Australian audience, even if the term “Dada” itself was not always explicitly invoked.

Max Harris and the Angry Penguins

Perhaps the most significant manifestation of Dadaist influence in Australia came through the literary and artistic journal Angry Penguins, founded by poet Max Harris in Adelaide in 1940. Though the journal embraced surrealism more explicitly than Dadaism, its radical approach to literature and art and its challenge to conservative Australian cultural values embodied the Dadaist spirit of rebellion.

The infamous Ern Malley affair of 1944, in which conservative poets James McAuley and Harold Stewart created a fictitious modernist poet to hoax Harris and the avant-garde, paradoxically became Australia’s most notorious Dadaist event—though unintentionally so. The deliberate nonsensical elements in the Ern Malley poems, created to ridicule modernism, ironically embodied Dadaist techniques of chance, absurdity, and the questioning of artistic authenticity.

While the hoaxers intended to discredit modernist experimentation, their creation instead became a compelling example of avant-garde poetry that has continued to fascinate readers and critics. The Ern Malley affair, with its blurring of authorship, intention, and artistic value, embodies the Dadaist challenge to conventional definitions of art, albeit through a uniquely Australian pathway.

The Spirited Connection: Dadaism and Australia’s Artistic Soul

In 1916, as the First World War engulfed Europe in unprecedented destruction, a radical artistic response emerged from the despair. Dadaism erupted as artists, writers, and performers sought to challenge the very rationality that had led the world into chaos. This revolutionary movement quickly evolved beyond political agitation into a profound questioning of artistic conventions themselves.

Marcel Duchamp’s infamous “Fountain” (1917)—a urinal signed with the pseudonym “R. Mutt” and presented as sculpture—epitomized Dada’s provocative stance by fundamentally challenging traditional notions of art and artistic value. Meanwhile, Max Ernst was laying groundwork that would later flourish in his Surrealist explorations, while Tristan Tzara’s performances at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire defined the movement’s theatrical audacity.

The Australian connection to this global artistic rebellion has distinctive characteristics. More than six decades have passed since Barry Humphries transformed a peak-hour train commute into an impromptu Dadaist performance by receiving breakfast service amidst bewildered passengers. This act exemplifies how Dadaism’s spirit found natural resonance with Australian cultural sensibilities.

Indeed, Australian artistic expression and Dadaist principles share profound affinities, particularly in their deployment of humor and absurdism as tools to captivate and challenge viewers. The Australian predilection for irreverence and questioning authority aligns naturally with Dada’s subversive ethos.

The Australian Dadaist artists featured below work across diverse media and techniques, yet each creates uniquely compelling works that continue this tradition of creative disruption and engaging absurdity. Their art demonstrates how Dadaism’s revolutionary spirit continues to inspire Australian creative expression in the contemporary world.

Australian Dada Artists

Stephen Benwell

Stephen Benwell: Bridging Dadaism and Contemporary Australian Art

Artist Profile

Stephen Benwell has established himself as one of Australia’s most significant ceramic artists since beginning his exhibition career in 1975. His international reputation rests on his masterful hand-built ceramics that explore multiple dimensions: functional vessels, innovative sculptural forms, and humanistic clay statues that engage with classical traditions while subverting them with contemporary sensibilities.

This exhibition highlights Benwell’s lesser-known works on paper, including two remarkable childhood drawings alongside later pieces. All exhibit the dreamlike imagination and conceptual depth that characterizes his broader artistic practice—qualities that connect his work to Dadaism’s legacy of challenging conventional representations.

Artist Statement

“…because if you have drawn it you’ve stated it. It’s a statement, you can explain it that simply. Because then that drawing exists. That is what art is. When we look at the history of art we just look at other people’s drawings of man. And they explain so much to us. You could not get a bigger task ever, that is the excitement of it all!” — Interview with Joe Pascoe, Benwell & Potter Ceramics Exhibition, Shepparton Art Gallery, 1989

Featured Work

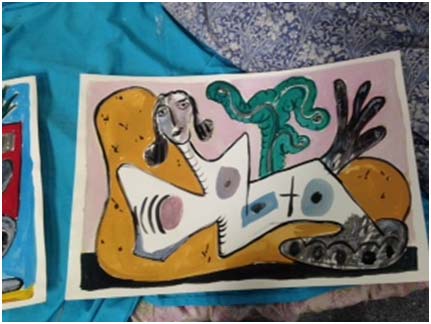

Reclining female

Acrylic on paper, 1988

Courtesy of Niagara Galleries

This work exemplifies Benwell’s exploration of the human form through a lens that both honors and questions artistic traditions. The reclining figure, a classical subject throughout art history, undergoes transformation through Benwell’s distinctive approach to form, color, and composition—creating a dialogue between historical representation and contemporary artistic expression.

Biography

Born in Melbourne in 1953, Benwell’s formal education culminated in a Master of Fine Arts from Monash University in 2005, though his artistic development spans decades of practice and experimentation.

Exhibition Highlights

Benwell’s artistic significance was affirmed with his major retrospective “Stephen Benwell: Beauty, Anarchy, Desire” at Heide Museum of Modern Art in 2013. His participation in “Dada lives!” at Hatch Contemporary Art Space (2015) explicitly acknowledges his connection to Dadaist traditions and their ongoing influence in Australian art.

His work has been featured in prestigious group exhibitions including “Melbourne Now” at the National Gallery of Victoria (2013), the Australian Ceramics Triennale (2012), and international showcases in Korea, New Zealand, Vietnam, the United States, and Germany.

Awards and Recognition

Benwell’s contributions to Australian art have been recognized with significant honors, including:

- Sidney Myer Fund Australian Ceramic Award (2010)

- Inaugural Deakin University Contemporary Small Sculpture Award (2009)

- Australia Council Visual Arts Board New Work Grant (2009)

- Monash Graduate Scholarship (2003-2007)

Critical Reception

Art critics have consistently praised Benwell’s unique vision. Robert Nelson (The Age) noted his ability to reconfigure “the dated and discredited” with contemporary twists, while John McPhee in Art and Australia explored the artist’s complex relationship with desire and form in “Ceramic Beefcake and other desires” (2009).

Through his multifaceted practice, Benwell continues the Dadaist tradition of questioning artistic conventions while creating works of exceptional technical skill and conceptual depth, establishing himself as a vital link between historical avant-garde movements and contemporary Australian artistic expression

Mark Cain: Confronting Artifice Through Dadaist Provocation

Artist Profile

Mark Cain has cultivated a fiercely independent artistic practice over decades, consistently challenging the established art world through a combination of exceptional craftsmanship and conceptual brilliance. His work embodies the Dadaist tradition of institutional critique while developing a distinctive contemporary voice that spans multiple media—from gallery installations to street art, interactive digital platforms, and experimental film.

Featured Work

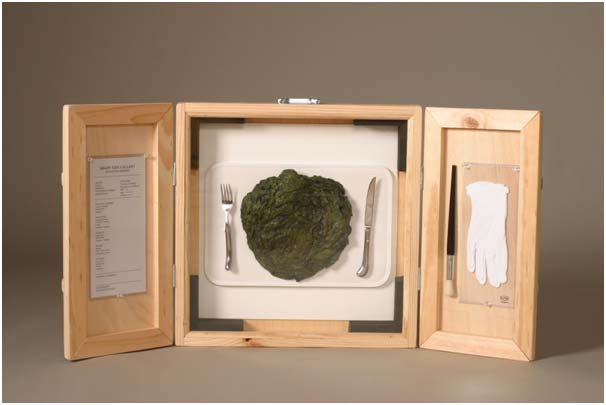

Thriving On Bullshit

Museum crate, fiberglass cow pat, mixed media, 2003

Collection of the Artist

This installation exemplifies Cain’s biting commentary on art world pretensions. By juxtaposing a professionally crafted museum crate—symbol of institutional validation and art market logistics—with a meticulously rendered fiberglass cow pat, Cain creates a visual pun that questions value systems, authenticity, and the packaging of artistic meaning. The work’s provocative title directly confronts viewers with its satirical intent, continuing Dadaism’s tradition of confronting artifice with irreverent humor.

Artist Statement

“At the core of my work is the need to communicate… Usually this takes the form of text, with a political and social immediacy. These messages and imagery are not always palatable, yet a sense of black humor permeates much of this oeuvre. Over the past twenty years, this work has been showcased through Galleries; an interactive Arts Website; Urban-based Stencil Art and Film.”

Artistic Evolution

Born in Shepparton, Victoria in 1959, Cain’s formal education includes a Diploma of Fine Art from Caulfield Institute of Technology (1977-79) and a Graduate Diploma of Education from Hawthorn Institute (1984). His artistic practice has continuously evolved while maintaining a consistent critical stance toward institutional frameworks.

Cain’s career demonstrates remarkable versatility, moving from traditional gallery exhibitions to pioneering digital platforms with the Shady Side Gallery interactive arts website (2006-2009), and further into urban environments as a street artist (2009-2013). His experimental film work, exemplified by Addled (available on YouTube), extends his critical vision into time-based media.

Exhibition History

Cain’s solo exhibitions reveal his consistent engagement with socio-political critique, including “Bullshit” at Shepparton Art Gallery (2006) and “Riding on the back of a pedigree horse” at the same institution. His participation in “Dada lives!” at Hatch Contemporary Art Space (2015) explicitly acknowledges his connection to the Dadaist tradition.

Professional Background

Since 1999, Cain has worked as a technician at Shepparton Art Museum, a position that has provided him with intimate knowledge of institutional practices while supporting his independent artistic voice. This dual perspective—working within the system while critiquing it—infuses his work with particular potency and insight.

His previous professional experience includes roles as a painting and drawing lecturer at Shepparton TAFE, an internship at the National Gallery of Victoria, teaching visual arts in Victoria’s prison system, and positions as an art teacher at various Melbourne colleges.

Through his multifaceted practice, Mark Cain continues the essential Dadaist mission of challenging conventions, exposing contradictions, and using provocative humor to confront audiences with uncomfortable truths about art and society. His work demonstrates how Dadaism’s revolutionary spirit remains vital in contemporary Australian artistic practice.

Anika Cook: Digital Dada for the 21st Century

Artist Profile

Anika Cook represents an emerging generation of artists whose creative practice has evolved alongside digital technology. Her work seamlessly navigates post-postmodern terrain, employing collage techniques that reconstruct fragments of contemporary reality into coherent narratives. While digital in execution, her artistic sensibility maintains deep connections to Dadaist predecessors, particularly Hannah Höch’s political satire and Max Ernst’s narrative-driven collage aesthetics.

Featured Work

Australian Politics series

Digital print, 2014

Courtesy of the Artist

This series exemplifies Cook’s contemporary application of Dadaist collage techniques to examine Australian political culture. By digitally assembling found imagery with deliberate juxtapositions and unexpected combinations, Cook creates visual commentaries that are simultaneously humorous and incisive. The work demonstrates how Dadaist approaches to fragmentation and recombination remain powerful tools for political critique in the digital age.

Artist Statement

“My work often features an underlying narrative that is sometimes amusing, sometimes a little absurd. Collage, with its elements of pre-existing meaning, seems a wonderful medium for this. This series for Dada Lives! takes a leaf out of the books of Hannah Höch and Max Ernst, nodding to Höch’s biting political satire while invoking Ernst’s delicate collage technique and use of dramatic narrative-driven imagery.”

Bridging Traditions and Technologies

Cook’s practice represents a fascinating bridge between historical Dadaist techniques and contemporary digital methodologies. While Höch and Ernst worked with physical materials—scissors, glue, and printed matter—Cook employs digital tools that allow for seamless integration and manipulation of visual elements. This technological evolution expands the possibilities of collage while maintaining the conceptual spirit of Dadaist disruption and recombination.

Multidisciplinary Practice

Beyond gallery exhibitions, Cook has developed a substantial practice as the designer and proprietor of The Gently Unfurling Sneak since 2004. This design business produces printed clothing, accessories, and limited edition artworks stocked in over 30 retail outlets and galleries throughout Australia. This crossover between fine art and commercial design reflects a contemporary extension of earlier Dadaist and Constructivist movements that sought to integrate artistic practice with everyday life.

Education and Professional Development

Cook’s educational background combines media studies at RMIT University with a completed Bachelor of Creative Arts from the University of Melbourne (2006) and postgraduate study in Design at Monash University. Her professional experience includes a significant role as Web and Design Coordinator at Craft Victoria (2008-2011) and ongoing freelance web design practice.

Her creative development has been supported by multiple grants, including an ArtStart grant from the Australia Council (2009), a Skills and Arts Development Emerging Artist grant (2008), and the Hannah Barry Memorial Prize from the University of Melbourne (2006).

Exhibition History

Cook’s work has been featured in diverse exhibition contexts, from the explicitly Dadaist “Dada Lives!” at Hatch Contemporary Art Space (2015) to fashion-oriented platforms like the Virgin Australia Melbourne Fashion Festival exhibition at Brunswick Street Gallery (2015). Earlier exhibitions include “Playing Field” at Craft Victoria (2010) and installations like “Gretel Was Getting Fatter” at Melbourne’s Sticky Institute (2005).

Through her multifaceted practice, Anika Cook demonstrates how Dadaism’s revolutionary approaches to image-making and meaning-creation continue to evolve in the digital era, offering new perspectives on politics, culture, and communication that remain as vital and subversive as their historical antecedents.

Nathalia – Darts & Dates: A Dadaist Experiment in Rural Australia

By William Kelly OAM & Joe Pascoe

It must have been provocation of a profound kind that led Marcel Duchamp to create such a deceptively simple artwork as Three Standard Stoppages in Paris, 1913-14.

To form this groundbreaking work, Duchamp dropped three one-metre threads from a height of one metre, allowing them to curl randomly where they landed. Each ‘stoppage’ was carefully traced and made permanent, then placed together in a museum-type box as the finalized artwork. This act of embracing chance—a cornerstone of Dadaist practice—created new standards of measurement that challenged conventional systems and perceptions.

Those with an Asperger’s sensibility might appreciate the cubic precision in Duchamp’s methodology—a metre-long string dropped from exactly one metre, repeated three times. The work exists without artistic precedent, embodying Dada’s revolutionary spirit. Some detect humor in it; perhaps, with a century of hindsight, it served as a conceptual critique of Cubism. We may never definitively “know” Duchamp’s intentions, though John Cage certainly recognized its significance, citing it as a direct inspiration for his groundbreaking composition 4’33”.

Dada in the Australian Countryside

There is a charming country town in Australia where artists William Kelly and his wife Veronica make their home. Nathalia, population 1,500, stretches gently across a generous river, framed by pepper trees and distinctive eucalypts, its axis marked by 19th-century buildings. The town exists under the watchful presence of that symbol of eternity—a water tower rising elegantly at the end of the main street. Soft side streets gradually dissolve into the fertile countryside. A setting such as this naturally evokes contemplation about the nature of time and artistic meaning.

Nathalia represents something of a “New Town” in contemporary Australia. Its residents are fully integrated with the wider digital world and diverse in their activities, religious practices, and artistic engagements. With its recently constructed library, hospital, and police station, the town’s demographic composition and rural centrality have attracted urban planners and inspired numerous artists.

The Duchampian Experiment

To recreate the spirit of Duchamp’s radical chance operations, internationally acclaimed artist and Nathalia resident William Kelly agreed to participate in an interview about three randomly selected days from his life. Just as each day contains precisely 24 hours and is “dropped” upon us to make meaning of, what shapes and patterns might be revealed through this Dadaist exercise? The specific dates were determined by throwing darts at a dartboard in Kelly’s home, witnessed by his wife Veronica—a contemporary Australian echo of Duchamp’s thread-dropping experiment.

Friday, 10 September 1949

“I was six years old and there were five of us sharing a single room in a rundown hotel in Buffalo, New York. We were there because my father was searching for work in Western New York. After several weeks, he secured a job as a switcher (switchman) on the railways—the workers who adjust tracks for trains. He remained in that position.

For breakfast, I typically had a piece of toast and a glass of water. I remember the weather was hot but primarily very, very humid. I slept directly on the floor, probably on a sheet—no bed.

During daylight hours, we played in the adjacent vacant lot. Like all children, we invented games such as throwing rocks at tin cans or occasionally a glass bottle, if one was available. I wasn’t attending school at that stage. Lunch consisted of another piece of toast, this time with a glass of milk. Our room lacked a power outlet, so we ran an electrical cord that connected to the light fitting. This had to be done surreptitiously, as ‘cooking’ was prohibited in the rooms.

On or around the day in question, it progressed like most others, with me playing in the vacant lot. However, toward late afternoon, my sisters went inside and some aggressive children arrived from elsewhere and cornered me. Amid punches and shoving, I was stabbed near my ankle. My father, I believe, carried me to the hospital where they cleaned the wound and inserted several stitches due to its jagged nature.

I had no dinner that night.

What stands out most in my memory is waking up happy despite everything.”

Saturday, 22 July 1967

“At approximately 24 years old, I was an art student in Philadelphia. I was working on a large family portrait, measuring about two meters square. The portrait depicted my family—my wife Veronica and our infant son Liam. Though the painting is now lost, I recall it showed Veronica reclining and myself standing nude, as reflected in a mirror. Liam appeared in a bassinet. The composition utilized primary colors and flesh tones.

By this time, breakfast had evolved to toast and poached eggs, accompanied by at least three cups of coffee. I smoked cigarettes whenever I could acquire them. My typical attire consisted of khaki clothing, a holdover from my previous occupation as a factory welder—short sleeves during summer months, long sleeves in winter.”

This Dadaist experiment in biographical chance operations reveals how personal history, like Duchamp’s fallen threads, creates unpredictable patterns that nevertheless form the foundation of artistic identity and practice. Through this intersection of Australian rural life and Dadaist methodologies, Kelly and Pascoe demonstrate the continuing relevance of Dada’s revolutionary approaches in contemporary artistic exploration.

William Kelly: A Dadaist Journey Through Time

Artist in Transition: Philadelphia to Race Riots

“My method then was to work full time for a year in the steel works and then dedicate an entire year to art school. We owned a 1963 Volkswagen Beetle in a cream color. My studio was simply a room in our apartment.

Being a Saturday, I would have gone to assist my friend and former lecturer, Paul Keene, with a mural commission he was completing for Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, North Carolina. Paul was African American, and the university was celebrating its centennial anniversary as a historically Black institution—established shortly after the Civil War.

I secured the position helping with the mural because Paul had broken his leg and was confined to a wheelchair, limiting how high he could reach. I essentially completed the top half from scaffolding while he worked on the bottom portion! He had meticulously sketched the design, and I blocked in the forms. As his leg improved, he gradually worked higher up the mural. Perhaps some of my brushwork remains visible to this day.

Paul was a cosmopolitan artist who had exhibited in Paris alongside Picasso and Léger and spoke fluent French. African Americans (then still referred to as ‘Negroes’ in America) typically received better treatment in Europe—particularly in France at that time.

It was late when I drove home around 8pm. Two blocks from our building, police had blockaded the streets due to an ongoing race riot. This period was marked by racial unrest, and beyond the widely reported riots where many lives were lost, numerous smaller disturbances occurred regularly. These were fueled by a combination of hot weather, end-of-week payday drinking, and deplorable living conditions. Gunshots echoed through the streets. I secured the car and made my way to our apartment. Veronica and Liam were fortunately unharmed. We waited for a relatively quiet period of twenty to twenty-five minutes before returning to retrieve the car and driving to Veronica’s mother’s house in rural Pennsylvania.

There was profound irony in spending the day working on a mural commemorating the founding of a Black university, only to find myself caught in a race riot that same night.”

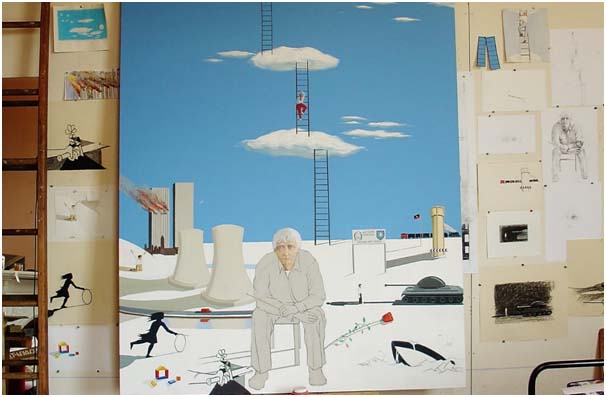

Contemporary Practice: Nathalia, 2013

Thursday, 7 November 2013

“Now at 70 years old, I make my home in Nathalia. The tranquility is remarkable, and Veronica and I enjoy breakfast together in our garden. The weather is exquisite, and I take pleasure in listening to the birds—striking yellow rosellas, magpies, wrens, and various smaller species. Breakfast has remained consistent: poached eggs and three cups of coffee!

I proceed to my studio where I’m developing a new painting titled Self-portrait in landscape: In the studio everyone is there with you (Courtesy MARS Gallery, Melbourne). The title emerged from a conversation with John Cage, whom I had spoken with on several occasions. On this particular day, I would have consulted art books featuring Picasso, Duchamp, De Chirico, and Goya. I often create small separate sketches of elements from their artworks, such as a detail from Goya’s 3rd of May.

The self-portrait was a deliberate attempt to reference people.

This composition features an expansive blue sky and a white lower plane. I’m depicted seated in the middle, in contemplation. On the reverse side of the canvas, I’ve carefully semi-stenciled the names of numerous individuals and artists who have influenced my development. Beyond the renowned figures, I include people like the Dixie Chicks who courageously challenged George W. Bush through their music. Their contributions matter equally.

At that stage of the process, I would have been blocking in the foundational elements of my painting. Around midday, Veronica often kindly brings me a cheese and tomato sandwich accompanied by a pot of coffee. I would have continued thinking and working—sometimes on the floor—throughout the afternoon, typically continuing until four or four-thirty in the morning, before rising again at eight or eight-thirty. This has always been my routine. Dinner would occur at some point, with a glass of wine around 10pm.

I maintain a fifteen-hour workday and always have.”

The Dadaist Thread

This random sampling of days from Kelly’s life, determined by chance operations reminiscent of Duchamp’s falling threads, reveals how artistic practice evolves while core elements remain consistent. From the struggling child in Buffalo to the politically engaged art student in Philadelphia to the established artist in rural Australia, certain constants emerge—the poached eggs, the extended working hours, the engagement with social issues, and the contemplative approach to making meaning from chaos.

Kelly’s work and life demonstrate how Dadaist principles of chance, juxtaposition, and challenging conventional systems continue to inform contemporary artistic practice. His self-portrait, which incorporates influences ranging from Duchamp to the Dixie Chicks, reflects the Dadaist tradition of collapsing hierarchies between “high” and “popular” culture, while his meticulous documentation of these random days echoes Duchamp’s precise measurement of seemingly random phenomena.

Through this experimental biographical approach, we witness how the spirit of Dada continues to thrive in unexpected places—even in the quiet countryside of Nathalia, Australia, where an internationally acclaimed artist contemplates both personal history and global influences while birds sing in the garden.

Nicholas Jones: Transforming Books into Sculptural Dadaist Objects

Artist Profile

Nicholas Jones has established himself as a masterful book sculptor over the past two decades, pioneering a distinctive reverse bas-relief technique that transforms discarded books into profound sculptural objects. By meticulously carving into the interior pages of found volumes, Jones creates new visual narratives that both honor and reimagine these repositories of knowledge. His practice resonates deeply with Dadaist traditions of transforming found objects and challenging conventional relationships between form, function, and meaning.

Featured Work

The Times Concise Atlas of the World

Carved book, 2014

Courtesy of the Artist

This sculptural intervention transforms a standard atlas—traditionally a tool for understanding spatial relationships and geographical boundaries—into a meditation on how knowledge is constructed, preserved, and reimagined. By carving into this atlas, Jones creates new topographies and unexpected landscapes within the physical body of the book itself, suggesting alternative ways of mapping and understanding our world. The work embodies the Dadaist tradition of revealing unexpected meanings within familiar objects.

Artist Statement

“…as much about the process as it is about the form… these books were conceived, born, loved, stored, discarded, found anew, studied, cut, folded and reborn.” — https://www.bibliopath.org/artwork/ (20/11/2014)

Artistic Evolution and Process

Jones’s approach to book sculpture has developed significantly since his early exhibitions in 1999. His technique involves carefully excavating the interior pages of books, creating negative spaces that transform these two-dimensional repositories of information into three-dimensional sculptural objects. This process resonates with Duchamp’s readymades—taking existing cultural artifacts and reconfiguring them to generate new meanings and perspectives.

His selection of “The Times Concise Atlas of the World” for this exhibition demonstrates his interest in works that already contain visual elements—maps, diagrams, illustrations—that can be reimagined through his interventive process. By carving into an atlas, Jones creates a dialogue between the book’s intended purpose (depicting geographical reality) and its new existence as an art object that challenges those very representations.

Exhibition History

Jones has maintained an active exhibition schedule since 1999, with solo exhibitions including “To the Islands” at Stockroom Gallery (2013), “Without Bias” at Craft Victoria (2010), and “The Garden of Forking Paths” at The Geelong Gallery (2009). His participation in “Dada lives!” at Hatch Contemporary Art Space (2015) explicitly acknowledges his connection to Dadaist traditions of object transformation.

His work has received international recognition, with exhibitions in Poland, Canada, and Chile, demonstrating the global resonance of his artistic approach. Notable group exhibitions include “Inspiration Under the Dome” at The State Library of Victoria (2013) and “Novel Ideas” at Oakville Gallery in Ontario, Canada (2009).

Artist-in-Residence and Community Engagement

Jones’s commitment to sharing his practice extends beyond exhibition venues. He has undertaken numerous artist residencies at institutions including the State Library of Victoria (2012), Melbourne Grammar School (2012), the Athenaeum Library (2012), and Geelong Grammar School (2009). During the “Dada lives!” exhibition, Jones serves as Artist-in-Residence, making himself available for special commissions and allowing visitors to witness his transformative process firsthand.

His work is represented in significant public and private collections throughout Australia, including the State Library of Victoria, The State Library of Queensland, The University of Melbourne, Artspace Mackay, and RMIT University.

Through his meticulous transformations of discarded books, Nicholas Jones continues the essential Dadaist tradition of challenging conventional relationships between objects and their meanings, creating works that invite viewers to reconsider both the physical nature of books and the cultural values they embody.

Anastasia Klose: The Personal as Dadaist Performance

Artist Profile

Anastasia Klose has emerged as one of Australia’s most significant contemporary artists by employing her own identity as an artistic medium. Her practice powerfully bridges the gap between art and life, preserving the raw energy of creation within each finished work. This approach resonates deeply with Dadaist traditions of collapsing boundaries between art and everyday experience, while speaking directly to contemporary concerns about identity, authenticity, and vulnerability in a digital age.

Born in Melbourne in 1978 and represented by Tolarno Galleries, Klose brings exceptional intellectual depth to her practice, having studied Philosophy and English at the University of Melbourne before completing her fine art training at the Victorian College of the Arts and receiving her Masters from Monash University in 2012.

Featured Work

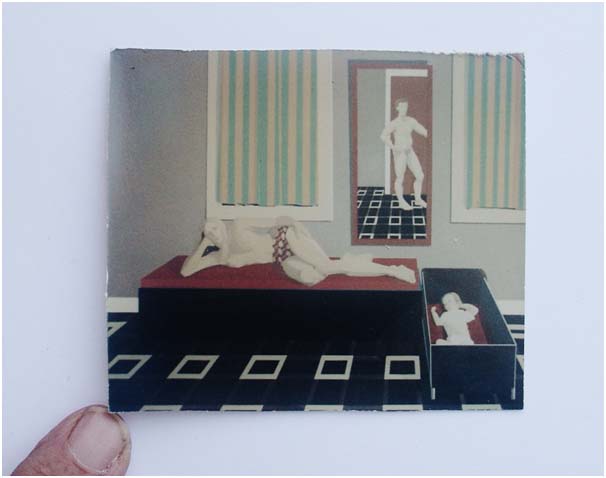

Self Portrait

Courtesy of Tolarno Galleries

This work exemplifies Klose’s distinctive approach to self-representation—not as narcissistic indulgence but as a carefully constructed artistic strategy. By placing herself within the frame, Klose creates a complex dialogue between artist, artwork, and audience, challenging traditional boundaries between creator and subject. This approach extends the Dadaist tradition of questioning artistic conventions while engaging directly with contemporary concerns about identity, authenticity, and performance in public and digital spaces.

Artist Statement

“Yes, my work is about my own ‘subjectivity’. But I am an artist, and it’s obviously not just a ‘dear diary here is my life’ outpouring. My work is extremely calculated. I think about it a lot before it happens. I consider my work very much from the perspective of the audience. I want them to get a certain ‘feeling’ when they see my work. I want them to feel like they’ve lived through whatever I’ve lived through themselves, whether they are man or woman. For example, ‘Film for my Nanna’, where I am the bride without a groom walking the streets, everyone could relate to that picture of loneliness. And in my live 2 month performance in Sydney last year at the MCA, ‘The Reliving Room’, I wanted people to feel sympathy and shame for me dancing, but I also wanted them to be amazed by my physical proximity. I wanted to create a sort of appalling, yet entertaining and compelling, atmosphere. Regarding audiences, the one thing I don’t want them to be is bored.” — Interview with Rachel Edgar

Calculated Vulnerability as Artistic Strategy

Klose’s work represents a sophisticated evolution of Dadaist approaches to performance and identity. While Dada artists often employed absurdist performances to challenge social conventions, Klose creates carefully calibrated emotional experiences that appear raw and spontaneous but are meticulously designed to elicit specific responses from viewers. This tension between authentic emotion and strategic presentation creates the distinctive power of her work.

Her performances, such as “Nanna, I am still searching…” at the 2011 Venice Biennale Vernissage (curated by Juliana Engberg for the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art), demonstrate how she transforms personal vulnerability into universal experience. By placing herself in situations of deliberate discomfort or potential humiliation, she creates encounters that resonate with audiences across demographic boundaries—a contemporary evolution of Dadaist strategies of provocation and audience engagement.

Exhibition History and Critical Recognition

Klose’s rapid rise to international recognition is reflected in her impressive exhibition history. Solo exhibitions include “I Can’t Stop Living” at Gertrude Contemporary and Tolarno Galleries (2012), and “The Poverty Show” at Tolarno Galleries (2010). Her work has been featured in significant group exhibitions including “Melbourne Now” at the National Gallery of Victoria (2013), “Primavera” at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney (2012), and “Contemporary Australia: Women” at the Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art (2012).

Her inclusion in “Dada lives!” at Hatch Contemporary Art Space (2015) acknowledges her connection to Dadaist traditions, while her participation in the 2008 Sydney Biennale (curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev) and international exhibitions in Italy, Sweden, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand demonstrate her global relevance.

Klose’s contributions to contemporary art have been recognized with several prestigious awards, including the $15,000 Prometheus Visual Art Award (2007), and her work is held in collections including Artbank, the University of Queensland Art Museum, and the Prometheus Foundation Gallery Collection.

Through her bold exploration of identity, vulnerability, and authenticity, Anastasia Klose continues the essential Dadaist mission of challenging artistic conventions and blurring boundaries between art and life, while speaking directly to contemporary experiences of selfhood in a digital age.

Kir Larwill: Finding Dadaist Poetry in Everyday Objects

Artist Profile

Kir Larwill is a printmaker and painter based in Castlemaine, Victoria, who works from a shared studio space in the town’s central business district and collaborates with fellow artist Diana Orinda Burns in Sandon. Her artistic practice embodies a contemporary interpretation of Dadaist sensibilities through her transformation of ordinary objects and familiar domestic spaces into works of unexpected beauty and significance. By elevating the mundane and utilitarian, Larwill continues the essential Dadaist tradition of finding profound meaning in overlooked aspects of everyday life.

Featured Work

The Mistress

Painted book, 2011

Courtesy of the artist

This painted book exemplifies Larwill’s distinctive artistic approach, which merges the visual language of painting with the narrative qualities of literature. By transforming a conventional book into a painted object, she creates a hybrid artwork that occupies its own physical and conceptual space—”like an imagined thought that has come to life.” This transformation of a functional object into an artwork with new meanings resonates with the Dadaist tradition of challenging conventional categories and finding poetry in unexpected places.

Artist Statement

“I am a printmaker and painter living and working in Castlemaine, Victoria. I have a small studio in a shared space in the Castlemaine CBD. I do my printmaking in this studio, or at the studio of friend and colleague Diana Orinda Burns, in Sandon. My work is generally about the beauty and meaning that can be found in the everyday, in the mundane and the utilitarian, and in the unremarkable corners of home. They are an exploration of household objects and familiar surrounds, and of the humour, weight and significance of ordinary things.”

Surrealist Elements and Personal Symbolism

While firmly rooted in her exploration of everyday objects, Larwill’s work often incorporates Surrealist elements and personal iconography. Boats and birds frequently appear as private symbols in her paintings, prints, and assembled objects, creating a distinctive visual language that bridges the gap between the material world and emotional states. This approach connects her to both Dadaist and Surrealist traditions of investing ordinary objects with extraordinary psychological significance.

Her painted books represent a particularly notable fusion of these influences. By transforming books—themselves repositories of narratives—into painted objects, she creates works that exist in multiple dimensions simultaneously: as visual art, as containers of stories, and as sculptural objects occupying their own distinctive space.

Exhibition History and Community Engagement

Larwill has presented her work in numerous solo exhibitions, including “Small Pleasures” at Union Studio Gallery, Castlemaine (2012), “Small Things” at Red Gallery, Fitzroy (2010), and “Home” at Red Gallery, Melbourne (2006). Her participation in “Dada lives!” at Hatch Contemporary Art Space (2015) explicitly acknowledges her connection to Dadaist traditions.

Her collaborative spirit extends beyond her artistic practice to significant community engagement. As a coordinator of the Castlemaine Artists’ Market, a member of the Castlemaine Press Inc. project team, and a participant in various initiatives to develop arts spaces in the Mount Alexander Shire, Larwill works actively to create opportunities for other artists and strengthen regional arts infrastructure.

Recognition and Collections

Larwill’s contributions to contemporary art have been recognized with numerous awards, including the Print Council of Australia Annual Print Commission (2012) and first prizes in various categories at the Beaufort Annual Show (2005, 2007, 2011, 2013). Her work is held in collections including the Counihan Gallery, Mount Alexander Hospital, State Library of Victoria, Canson Australia, Print Council of Australia Archive, City of Freemantle Art Collection, and the private collection of prominent Australian barrister Julian Burnside QC.

Through her thoughtful exploration of everyday objects and domestic spaces, Kir Larwill continues the essential Dadaist mission of finding unexpected poetry and significance in the overlooked corners of ordinary life, while developing a distinctive contemporary artistic voice deeply rooted in regional Australian experience.

Elizabeth Liddle: Indigenous Perspectives Through Dadaist Intervention

Artist Profile

Elizabeth Liddle is an emerging artist whose multidisciplinary practice powerfully addresses contemporary, historical, and cultural issues through the dual lens of her immediate surroundings and Indigenous heritage. Working across diverse media including installation, photography, and digital art, Liddle creates conceptually sophisticated works that challenge conventional narratives about Australian history and identity. Her approach embodies Dadaist strategies of disruption and recontextualization while speaking directly to the specific cultural and historical experiences of Indigenous Australians.

Featured Work

The Entry Mat, 1788

Rubber-backed coir matting, acrylic gloss paint

Size: within 3 x 3 metres

This installation transforms a commonplace household object—a doormat—into a potent symbol of colonization and cultural disruption. By recreating Norman Tindale’s map of Aboriginal language groups on a doormat using traditional coir matting and acrylic paint, Liddle creates a multilayered commentary on Australian history and cultural identity.

The work functions simultaneously as a literal “welcome mat” and as a representation of the land that became Australia. The black lines delineating diverse tribal groups who spoke regionally distinct languages create a visual pattern that challenges the imposed state borders of modern Australia. The material itself—a doormat designed to be walked over—serves as a powerful metaphor for colonization and the subsequent treatment of Indigenous peoples and their cultures.

Through this Dadaist recontextualization of both map and mat, Liddle creates a work that invites viewers to physically and conceptually “step onto” a representation of pre-colonial Australia, making them physically complicit in the act of crossing boundaries and potentially “wiping their feet” on Indigenous cultural heritage.

Artist Statement

“The Entry Mat, 1788 is an installation work that is presented as a modern doormat representing the island now known as Australia. Based on Norman Tindale’s original Aboriginal language map, the work represents Aboriginal nationhood up to 1788, the year in which New Holland became a British colony called New South Wales. Australia, as we know it today is divided and classified through our modern state borders.

The black lines are representative of diverse tribal groups who speak regionally distinct languages and also share cultural practices and customs. 1788 marked the time when masses of Britain’s free and unwanted citizens entered the country in waves of tall ship arrivals and is symbolic of the experiences of Aboriginal people thereafter.”

Conceptual Depth and Cultural Commentary

Liddle’s work in “Dada Lives!” demonstrates exceptional conceptual sophistication in its engagement with the complex history of Australian colonization and Indigenous experience. By employing the Dadaist strategy of recontextualizing everyday objects, she transforms a utilitarian doormat into a powerful vehicle for cultural critique and historical reflection.

The work creates multiple layers of meaning: the doormat represents both the physical land and the concept of welcome/entry; the Aboriginal language map challenges imposed colonial borders; and the act of viewers potentially walking across this representation enacts a physical metaphor for historical disregard of Indigenous sovereignty. This multilayered approach reflects the Dadaist tradition of creating objects that function simultaneously as art and as critical commentary on social and political conditions.

Exhibition History and Recognition

Liddle’s participation in “Dada Lives!” at Hatch Contemporary Art Space (2015) positions her work within the context of Dadaist artistic traditions while maintaining its distinctive cultural specificity. Her work has been featured in significant exhibitions including “Horizons” at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre (2014), “Indigenous Voices, Contemporary Strategies” at Incinerator Gallery (2013), and “BengeknyarrwaBengoot.ErrantherreYengeeweme (Wadawurrung/Arrernte), I see you, I hear you” at Manningham Art Gallery (2013).

Her artistic contributions have been recognized with notable distinctions, including being named a finalist in the Substation Contemporary Art Prize (2013) and winning the Inaugural DESA Award for Indigenous Artists (2010) for her digital photograph “Sulphur Crested Cockatoo Feather.”

Liddle’s work is held in several collections, including Manningham City Council Art Gallery, Relationships Australia, and DESA Australia, demonstrating the growing recognition of her significant contribution to contemporary Australian art.

Through her thoughtful integration of Indigenous perspectives with Dadaist strategies of disruption and recontextualization, Elizabeth Liddle creates work that challenges viewers to reconsider their understanding of Australian history, identity, and the ongoing impact of colonization on Indigenous communities.

John O’Neil: Documenting Australia with a Dadaist Eye

Artist Profile

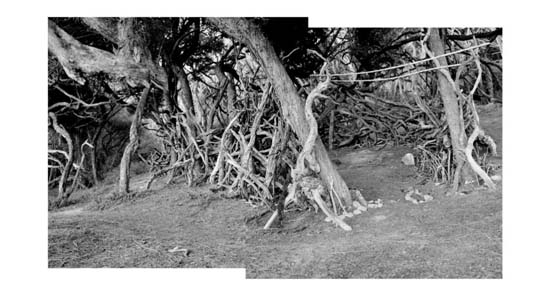

John O’Neil has established himself as a significant photographer over several decades, capturing the Australian landscape with a distinctive vision that spans from primeval natural settings to contemporary commercial environments. His career has evolved through various professional roles, including Senior Photographer at Deakin University’s Visual Art and Media Departments, Photography Teacher, and currently as a Professional Photographer operating his own business. Throughout these transitions, O’Neil has maintained a consistent artistic practice alongside his commercial work, developing a unique photographic language that resonates with Dadaist approaches to seeing and representing reality.

Featured Work

Ironbark

Digital print, 1983

Courtesy of the Artist and Bridget McDonnell Gallery

This work exemplifies O’Neil’s ability to transform ordinary landscape elements into images of profound significance. The ironbark—a quintessentially Australian eucalypt known for its distinctive dark, deeply furrowed bark—becomes more than merely a documentary subject through O’Neil’s lens. His photographic approach reveals the tree’s sculptural qualities and textural complexity, finding abstract patterns and unexpected beauty in this common Australian species.

The print’s dating to 1983 (likely from an original film negative later digitized) places it within a crucial period in Australian photography when practitioners were beginning to receive serious critical attention from major institutions. During this era, O’Neil was developing his distinctive approach to landscape photography, including the bushfire series that would later achieve iconic status for its powerful depiction of Australia’s cycle of destruction and renewal.

Artist Statement

“I initially came to Torquay after being employed by Deakin University, Visual Art and Media Departments as Senior Photographer, subsequently I became a Teacher of Photography, Art and Media. Currently I am a Professional Photographer (John O’Neil Photography) doing advertising photography, weddings and portraits. My education is in the visual arts and I have always maintained an interest in art and photo/art and at times I have been very actively involved producing it, I welcome this opportunity to display this work ‘some old some new’.” — www.johnoneilphotography.com/

The Dadaist Perspective in Australian Landscape

O’Neil’s approach to landscape photography embodies certain Dadaist sensibilities through his ability to find unexpected beauty and meaning in overlooked or ordinary aspects of the Australian environment. His renowned bushfire series transcends straightforward documentation to capture what has been described as “the soul of a burnt landscape, with its promise of eternal survival”—revealing deeper metaphysical qualities beneath the visible surface.

This transformation of the ordinary through the photographic gaze connects O’Neil’s work to the Dadaist tradition of finding new significance in common objects and familiar scenes. By isolating particular elements of the landscape and presenting them through a carefully composed frame, O’Neil invites viewers to reconsider their relationship with the Australian environment—seeing with fresh eyes what might otherwise be taken for granted.

Exhibition History and Institutional Recognition

O’Neil’s artistic contributions have been recognized through inclusion in significant exhibitions at major Australian institutions. His work was featured in “Stormy Weather, Contemporary Landscape Photography” at the National Gallery of Victoria (2011), the prestigious Moet and Chandon Prize at the National Gallery of Victoria (1989), and “Australian Landscape Photographed,” which traveled between the Art Gallery of NSW, National Gallery of Victoria, and Ballarat Art Gallery (1986).

His haunting documentation of the devastating 1983 Ash Wednesday bushfires was exhibited at the Australian Centre for Photography (1984), representing an important contribution to Australia’s visual record of this significant historical event. Other notable exhibitions include “Thousand Mile Stare” at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (1989) and “Victoria Vision – 1834 Onwards” at the National Gallery of Victoria (1985).

Collections and Legacy

O’Neil’s photographs are held in several significant public collections, including the National Gallery of Victoria, Geelong Art Gallery, Deakin University Collection, Melbourne City Council Collection, and the Moet and Chandon Collection, as well as numerous private collections. This institutional recognition affirms his important contribution to Australian photography.

Through his distinctive photographic vision, John O’Neil continues to reveal unexpected aspects of the Australian landscape, finding profound meaning in both natural environments and human interventions. His work demonstrates how a Dadaist sensibility—the ability to transform ordinary subjects through a shift in perspective—can illuminate new dimensions of the familiar Australian environment.

Stefan Szonyi: Miniature Worlds with Dadaist Imagination

Artist Profile

Stefan Szonyi has established himself as one of Australia’s most distinctive ceramic artists, creating miniature worlds that capture profound narratives within the palm of a hand. Born in Germany in 1945 and arriving in Australia in 1949, Szonyi brings a unique perspective to his artistic practice, informed by both his European heritage and Australian experience. His formal education includes teacher training at Melbourne Teacher’s College (1964-66), painting studies at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (1967), and further art education at Preston Institute of Technology (1979-81). Currently based in Daylesford, Victoria, Szonyi has developed a body of work that combines technical mastery with philosophical depth and playful humor.

Featured Work

Studio 1

Ceramic, 1994

Courtesy of the Artist

This piece from Szonyi’s “In The Studio” series exemplifies his meticulous approach to miniaturization and his interest in the artistic process itself. By creating a diminutive ceramic representation of an artist’s studio, Szonyi engages in a form of meta-commentary on artistic production and the spaces where creativity unfolds. This self-referential quality connects his work to Dadaist traditions of questioning and examining the nature of art itself.

The work demonstrates Szonyi’s exceptional technical skill in combining clay with other materials to create detailed, narrative-rich compositions that invite close inspection and contemplation. His background in painting is evident in the vibrant use of color through underglazes, creating a visually striking object that rewards careful examination.

Artist Statement

“Two of these works are from the ‘In The Studio’ series while the other work is from a ‘Big’ series. They are all simply observations and reflections on recalled and selected events, combined with an element of autobiography and social commentary.

The work incorporates a natural fascination with miniatures and is an attempt to come to terms with the challenges involved in construction using clay combined with other materials.

The earthenware clay and underglazes used in this work seemed to be the ideal materials to challenge my need to engage in modelling and attempting to make well crafted, colourful objects. My training in painting imbued me with a love of colour and I have primarily been motivated by the joy and pleasure derived from viewing and handling brightly coloured ceramic objects.”

Dadaist Elements in Miniature Form

Szonyi’s ceramic works embody several qualities that connect them to Dadaist traditions while establishing a distinctive contemporary voice. His miniature scenarios often incorporate elements of absurdist humor, unexpected juxtapositions, and social commentary—all hallmarks of the Dadaist approach to art-making.

The “unique philosophical qualities of Australian humour” that characterize his work reflect a particular sensibility that combines wry observation with playful critique. By creating tiny ceramic tableaux that explore themes such as “family love, chance and some of the constructs in the art world,” Szonyi invites viewers to reconsider familiar aspects of human experience through an altered perspective—a fundamental Dadaist strategy.

His miniature works function as what might be described as “pocket museums”—small-scale environments that preserve and present carefully constructed narratives. This approach resonates with the Dadaist interest in creating alternative systems of meaning and value through artistic intervention.

Exhibition History and Institutional Recognition

Szonyi’s artistic contributions have been recognized through numerous solo exhibitions, including a major touring exhibition “Stefan Szonyi Surveyed” (1992-93) that visited regional galleries in Ballarat, Bendigo, Benalla, Shepparton, and Geelong, as well as the Roy Morgan Research Centre in Melbourne. His work has been shown at prestigious galleries including Ray Hughes Gallery in Sydney and Brisbane and Macquarie Galleries in Sydney.

He has participated in significant international exhibitions including the 37th International Exhibition of Ceramic Art in Faenza, Italy (1979), “Contemporary Australian Ceramics” touring New Zealand, Canada, and the USA (1982-84), and the International Ceramics Festival in Mino, Japan (1985). His inclusion in “Delinquent Angel-Australian ceramics” touring Faenza, Italy, Asia, and Australia (1996-97) further confirms his international recognition.

Collections and Legacy

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Szonyi’s career is the exceptional institutional collection of his work. As noted in his resume, “probably more than half of his ceramics now reside in public collections,” a rare achievement for any artist. His works are held in numerous significant collections including the National Gallery of Australia, National Gallery of Victoria, Art Gallery of South Australia, Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, and regional galleries throughout Australia, as well as international collections such as the Comune Di Faenza Collection in Italy.

This extensive institutional representation speaks to the recognized significance of Szonyi’s contribution to Australian ceramics and his distinctive voice within contemporary art. Through his miniature ceramic worlds, Stefan Szonyi continues the Dadaist tradition of finding profound meaning and unexpected connections in carefully constructed artistic environments, while adding his uniquely Australian perspective and technical mastery to this ongoing conversation.

Dadaism In Australia

Other Notable Dada Artists in Australia

While Dadaism originated in Europe, its influence reached Australia where several artists embraced its revolutionary spirit. Here are some notable Australian artists who have incorporated Dadaist principles into their work:

- Mike Parr – One of Australia’s most significant performance and conceptual artists whose self-mutilating performances and provocative installations challenge conventional art boundaries in true Dadaist fashion. His work often explores identity, politics, and the human body through confrontational means.

- Pat Larter – A pioneering mail artist and performance artist who embraced Dadaist collage techniques and anti-establishment ethos in her feminist-oriented work. Her “Larter Mailart Archive” represents an important Australian connection to the international mail art movement that evolved from Dadaist principles.

- Richard Larter – Husband of Pat Larter and significant pop artist who incorporated elements of Dadaist collage and appropriation in his vibrant, politically charged paintings that challenged Australian artistic conventions in the 1960s and 70s.

- Aleks Danko – Conceptual artist whose playful, text-based works and installations often employ Dadaist humor and absurdity to critique Australian cultural identity and artistic institutions.

- Robert Klippel – While primarily known as an abstract sculptor, Klippel’s assemblages of found mechanical objects show strong Dadaist influences in their transformation of everyday materials into surreal constructions.

- Imants Tillers – Contemporary artist whose appropriation techniques and large-scale canvas board assemblages reflect Dadaist strategies of juxtaposition and questioning authorship and originality.

- Peter Tyndall – Conceptual artist whose work frequently incorporates text, symbols, and imagery in Dadaist-inspired arrangements that challenge artistic conventions and meaning-making.

- Juan Davila – Chilean-born Australian artist whose provocative paintings incorporate elements of collage, text, and appropriation in a manner that extends Dadaist tactics to critique politics and sexuality.

- Ken Whisson – Painter whose deliberately “deskilled” aesthetic and chaotic compositions reflect Dadaist rejection of traditional artistic mastery in favor of spontaneity and psychological expression.

- Gareth Sansom – Painter and collagist whose work combines elements of expressionism with Dadaist juxtapositions of incongruous imagery and materials to create psychologically charged compositions.